According to data from the most recent IPCC assessment, even so-called “unchecked” climate change would probably only mean that our great-grandkids will see a smaller increase in their standard of living than they otherwise would have. In other words, explains Bob Murphy in this guest post, it would probably merely mean that people in the year 2100 will only be a lot richer than we are, as opposed to a whole lot richer...

An Earth scientist’s recent article currently circulating around social media highlights a terrifying conversation he had with “a very senior member” of the IPCC, which is the UN’s body devoted to studying climate science. The upshot of their conversation was that millions of people will die from climate change, a conclusion that leads the author to lament that humans have created a consumption-driven civilization that is “hell-bent on destroying itself.”

As with most such alarmist rhetoric, there is little to document these sweeping claims—even if we restrict ourselves to “official” sources of information, including the IPCC reports themselves. The historical record does not justify panic, but instead should lead us to expect continued progress for humanity, so long as the normal operation of voluntary market interactions continues without significant political interference to sabotage it.

The Conversation

Here is the opening hook from James Dyke’s article, in which he grabs the reader with an apocalyptic conversation:It was the spring of 2011, and I had managed to corner a very senior member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) during a coffee break at a workshop…Putting aside (if you can) the creepiness of someone smiling as he predicts millions of deaths—sort of like a James Bond villain—we must enquire: How plausible are these warnings? Does the climate change literature actually support such bold projections?

The IPCC reviews the vast amounts of science being generated around climate change and produces assessment reports every four years. Given the impact the IPPC’s findings can have on policy and industry, great care is made to carefully present and communicate its scientific findings. So I wasn’t expecting much when I straight out asked him how much warming he thought we were going to achieve before we manage to make the required cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

“Oh, I think we’re heading towards 3°C at least,” he said.

…

“But what about the many millions of people directly threatened,” I went on. “Those living in low-lying nations, the farmers affected by abrupt changes in weather, kids exposed to new diseases?”

He gave a sigh, paused for a few seconds, and a sad, resigned smile crept over his face. He then simply said: “They will die.”

As it turns out, the answer is “no.” It is certainly true that there are many particular dangers regarding climate change, which could have deleterious consequences on human welfare (broadly defined). But in order to conclude that millions of deaths hang in the balance—or even billions, as the author of the article states in his concluding remarks—we have to grossly exaggerate all of the various mechanisms and scenarios, and we have to assume that humans do nothing at all to adapt to the changing circumstances over the course of decades.

In reality, it is much more likely that humans will adapt to whatever changes the climate brings them in the coming decades, and that various measures of human well-being—including not just GDP but also life expectancy and declining mortality rates from various ailments—will continue to improve. The voluntary market economy is an excellent general-purpose solution to the challenges facing humanity, including the handling of whatever curveballs climate change might throw.

IPCC’s Summary of Climate Change Damages

Unfortunately, it is difficult to come up with a statistic such as, “How many excess deaths does the IPCC predict from climate change by the year 2100, if governments don’t take further action?” If you consult the AR5, which is the latest IPCC report, and look at chapter 11 (Working Group II) on the impacts of climate change on human health, you will see various trouble areas and figures concerning at-risk populations, but nothing so crisp as to allow us to evaluate the casual claims of millions of deaths.However, the IPCC chapter does tell us upfront:

The Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) pointed to dramatic improvement in life expectancy in most parts of the world in the 20th century, and this trend has continued through the first decade of the 21st century (Wang et al., 2012). Rapid progress in a few countries (especially China) has dominated global averages, but most countries have benefited from substantial reductions in mortality. There remain sizable and avoidable inequalities in life expectancy within and between nations in terms of education, income, and ethnicity (Beaglehole and Bonita, 2008) and in some countries, official statistics are so patchy in quality and coverage that it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about health trends (Byass, 2010). Years lived with disability have tended to increase in most countries (Salomon et al., 2012).

If economic development continues as forecast, it is expected that mortality rates will continue to fall in most countries; the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the global burden of disease (measured in disability-adjusted life years per capita) will decrease by 30% by 2030, compared with 2004 (WHO, 2008a). The underlying causes of global poor health are expected to change substantially, with much greater prominence of chronic diseases and injury; nevertheless, the major infectious diseases of adults and children will remain important in some regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Hughes et al., 2011). [IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Working Group II, Chapter 11, bold added.]

Later in that same chapter, we see the following table, which is illustrative of the general pattern when it comes to long-term projections about climate change harms to humanity:

|

| Source: IPCC AR5, Working Group II, Chapter 11 |

As I have explained—most recently in this article—when it comes to climate change, the big projected damages don’t occur until many decades into the future. But for those people, standard economic growth will have raised their baseline standard of living by so much, that even if the UN-endorsed best-guess projections of climate change are accurate, those humans will still be much better off than we are today.

“It’s Getting So Much Better All the Time”

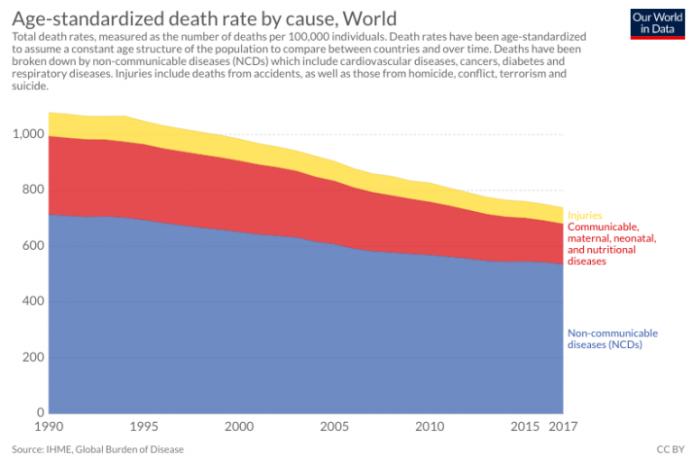

To see more evidence of this pattern, consider the following chart depicting mortality from various causes, created by Our World in Data using data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2018:

As the chart indicates, the death rates from various types of causes have fallen sharply around the world, particularly those from communicable diseases, and all within the last 20 years—when climate change was ostensibly becoming a deadly problem for humanity that only “deniers” could ignore.

For another line of evidence, let me show you a table where the UN did give us some measures of “aggregate” damages from climate change. Specifically, in chapter 10 of the AR5 we see the following table summarising the climate change economics literature on the subject:

|

| Source: Table 10.B.1, IPCC AR5, Working Group II, p. 82. |

As the table summarises, even for warming of three degrees Celsius, all but one of the studies predicted non-alarming amounts of damage. (I discuss the table more in this article.) Now I should emphasise that although the impacts are measured in GDP terms, these damage estimates include things like impacts on human health and mortality. It isn’t simply a measured reduction in the flow of TV output because some of the factories are under the sea.

In any event, it should be clear from the table that—contrary to James Dyke—we should not expect millions, let alone billions (!), of people to die from climate change. Even if climate change proceeds as the peer-reviewed literature assumes in the most pessimistic emissions scenarios, it will probably merely mean that people in the year 2100 will only be a lot richer than we are, as opposed to a whole lot richer.

What About the Catastrophic Scenarios?

Now it’s true, nobody can guarantee that there won’t be a climate change catastrophe. But we must realise that at least several of the featured studies warning of huge negative impacts are based on obviously flawed assumptions.Oren Cass provides us with some examples. One study looked at the increase in mortality in a cold, northern US city during a particularly brutal summer, and then extrapolated to show a staggering number of excess heat deaths decades down the road, when such “bad summers” were more common. Yet in the projections, the northern cities were no hotter than southern US cities are right now, and yes these southern cities don’t have nearly the same heat death rate as is projected for the northern cities decades down the road.

What is happening here should be obvious after a moment’s reflection: A northern city like Philadelphia is not adapted to hot summer the way Houston or Las Vegas is. But if climate change did indeed make such temperatures the norm—over the course of several decades —then the residents of the northern cities would adapt. The most alarming of the projections of climate change damages rely on naïve assumptions about human adaptability. They would install more air conditioning, and the people born in the year (say) 2080 would be much better able physically to cope with higher temperatures in 2100 than the people alive today.

This is also the general response I would give the issue of sea-level rise. I think that much of the rhetoric here is overblown, but even to the extent that it is true, we don’t need to worry about millions of people literally dying. Even if true, this is a problem that will manifest itself over several generations. If certain coastal regions are truly threatened, then in the worst case humans will stop building (and eventually even repairing) the houses and businesses near the rising seas. Humans can gradually move out of these (sinking) neighbourhoods and go further inland, through a process of attrition rather than mass migration in the face of a tidal wave.

The climate change alarmists are given a free pass to throw out the most absurd rhetoric, such as a recent author’s warning that potentially billions of people could die because of human-caused climate change. Yet despite their claimed fidelity to the “consensus science,” such claims are not supported by the UN’s own climate change reports.

The most alarming of the projections of climate change damages rely on naïve assumptions about human adaptability. Even if we stipulate the basic projections made in the most recent IPCC assessment, what “unchecked” climate change will probably mean is that our great-grandkids will see a smaller increase in their standard of living than they otherwise would have, if some of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could have been costlessly removed. Such a possible outcome is no reason to panic, and it doesn’t justify massive government intervention in the energy or transportation sectors.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Robert P. Murphy is senior economist at the Independent Energy Institute, a research assistant professor with the Free Market Institute at Texas Tech University, and a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute.

This article first appeared at the Mises Blog.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment