Ever the populist, Police Minister Judith Collins has announced what she calls “a multi pronged attack on gangs” and a plan to “tackle drugs, illegal gains and firearms.”

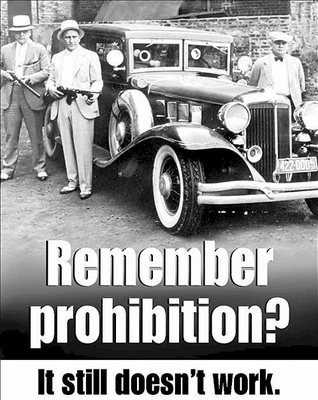

But you can’t talk sensibly about a War on Gangs without also talking about the government’s War on Drugs. Not properly. As the prohibition of alcohol proved so conclusively in America—coinciding as that sorry period did with the birth of big criminal gangs there – where you have prohibition, you have a ready income stream for criminal organisations. (It was prohibition, if you like, that caused the Greatness of Gatsby.)

You might have thought then that ripping away their secure income stream would have been the obvious “prong” with which a police minister might begin attacking gangs. Even the most obvious.

Challenged on this point on Morning Report this morning however, Collins airily dismissed the notion. Accepting that gangs’ "primary income is from selling drugs," she was Asked by Espiner what would happen to gangs’ finances if marijuana were legalised, Collins rather bizarelly insisted that they would then get into legalised prostitution and harder drugs like methamphetamine.

But this is nonsensical. A Justice Ministry study that Collins could easily have read in her previous post found that during the in-depth interviews of 656 sex workers “there was no mention of gang involvement or coercion.” Overseeing the research, the Ministry’s Prostitution Law Reform Committee considered “that the links between crime and prostitution are tenuous. The Committee could not find any evidence of a specific link between crime and prostitution.”

The notion is as bizarre as her claim that legalising marijuana, for example, would see an explosion of methamphetamine being sold on the street. As thousands of current and former members of law enforcement who support drug regulation rather than prohibition argue—including Scotland Yard’s former head of drug policing—prohibition doesn’t mean people stop consuming drugs, they just change the drugs they're consuming.

Here, Collins could benefit from getting to grips with what Milton Friedman called The Iron Law of Prohibition: which says that the more you actively prohibit drugs, then it is the more virulent drugs you actively encourage.

Friedman proved, for example, that prohibition changes the way people use drugs, making many people use stronger, more dangerous variants than they would in a legal market.

During alcohol prohibition, moonshine eclipsed beer; during drug prohibition, crack is eclipsing coke. He called his rule explaining this curious historical fact “the Iron Law of Prohibition”: the harder the police crack down on a substance, the more concentrated the substance will become.

Why? If you run a bootleg bar in Prohibition-era Chicago and you are going to make a gallon of alcoholic drink, you could make a gallon of beer, which one person can drink and constitutes one sale – or you can make a gallon of pucheen, which is so strong it takes thirty people to drink it and constitutes thirty sales. Prohibition encourages you produce and provide the stronger, more harmful drink.

If you are a drug dealer in Hackney, you can use the kilo of cocaine you own to sell to casual coke users who will snort it and come back a month later – or you can microwave it into crack, which is far more addictive, and you will have your customer coming back for more in a few hours. Prohibition encourages you to produce and provide the more harmful drug.

For Friedman, the solution was stark: take drugs back from criminals and hand them to doctors, pharmacists, and off-licenses. Legalise. Chronic drug use will be a problem whatever we do, but adding a vast layer of criminality, making the drugs more toxic, and squandering £20bn on enforcing prohibition that could be spent on prescription and rehab, only exacerbates the problem [and helps raise the profits for gangs].

Collins talks about offering “a path out of gangs.” If she’s serious, then most obvious is to make them unprofitable.

After all, it’s working exactly that way in Mexico, where legalising American weed has been off killing drug cartels.

In fact, as both Ethan Nadelmann of the N.Y.C.-based Drug Policy Alliance and Richard Branson, the chairman of Virgin Group point out: drug legalisation is pretty much the worst thing that could happen to organized crime.*

Are you listening, Judith?

RELATED POSTS:

- Don’t like drugs? Then legalise cannabis. – NOT PC

- "Stop arresting people for drugs and start offering help" – NEWSHUB

- Legal US Weed Is Killing Drug Cartels – Jonah Bennett, DAILY CALLER

- The Only Thing Drug Gangs and Cartels Fear Is Legalisation – Johann Hari, THE WORLD POST

- Prohibition Caused the Greatness of Gatsby – NOT PC

- Friedman's "Iron Law of Prohibition" – Clark & Watkins, SUN LIVE

- Portugal’s Experiment in Drug Decriminalisation Has Been a Success – Mark Thornton, MISES INSTITUTE

- The Economist explains: The difference between legalisation and decriminalisation- THE ECONOMIST

* Note that they say legalisation, not merely decriminalisation. Decriminalisation can mean that it’s legal to enjoy drugs but still illegal to sell them. Portugal, for example decriminalised every imaginable drug, from marijuana, to cocaine, to heroin in 2001, to discover that to discover that drug use went down rather than up, that the drugs being consumed were far safer than they were before, and most importantly Portugal now enjoys the second-lowest death rate from recreational drugs in all of Europe (after experiencing one of the worst rates with prohibition)

But because the selling of those drugs in Portugal is stil illegal, it is still largely in the hands of gangs – who are certainly being nicer than they were, but are still at heart just gangsters. “Decriminalisation’s flaw,” notes the Economist, “is that it does nothing to undermine the criminal monopoly on the multi-billion-dollar drugs industry. The decriminalised cocaine consumed without criminal consequences in Portugal is still supplied by the gangs who cut off heads in Colombia. Washington, DC’s version of legalisation is similarly flawed: although possession has been legalised, Congress has prevented the city from legalising the buying and selling of the drug. The capital’s pot business will therefore remain a criminal monopoly. The new law is good news for the people who harmlessly get high. But unless it is followed up eventually by legalisation of the supply-side of the business, it is [still] good news for the crooks who sell it.”

2 comments:

I think we know who the biggest and most most ruthless gangs are, those that are democratically elected.

Or she could just enforce section 98A of the Crimes Act and eliminate gangs by lunchtime....

98A Participation in organised criminal group

(1)

Every person commits an offence and is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years who participates in an organised criminal group—

(a)

knowing that 3 or more people share any 1 or more of the objectives (the particular objective or particular objectives) described in paragraphs (a) to (d) of subsection (2) (whether or not the person himself or herself shares the particular objective or particular objectives); and

(b)

either knowing that his or her conduct contributes, or being reckless as to whether his or her conduct may contribute, to the occurrence of any criminal activity; and

(c)

either knowing that the criminal activity contributes, or being reckless as to whether the criminal activity may contribute, to achieving the particular objective or particular objectives of the organised criminal group.

(2)

For the purposes of this Act, a group is an organised criminal group if it is a group of 3 or more people who have as their objective or one of their objectives—

(a)

obtaining material benefits from the commission of offences that are punishable by imprisonment for a term of 4 years or more; or

(b)

obtaining material benefits from conduct outside New Zealand that, if it occurred in New Zealand, would constitute the commission of offences that are punishable by imprisonment for a term of 4 years or more; or

(c)

the commission of serious violent offences; or

(d)

conduct outside New Zealand that, if it occurred in New Zealand, would constitute the commission of serious violent offences.

(3)

A group of people is capable of being an organised criminal group for the purposes of this Act whether or not—

(a)

some of them are subordinates or employees of others; or

(b)

only some of the people involved in it at a particular time are involved in the planning, arrangement, or execution at that time of any particular action, activity, or transaction; or

(c)

its membership changes from time to time.

Post a Comment