Interesting to see that in speaking at the Act Conference over the weekend, Alan Gibbs was promoting the reintroduction of a gold standard.

About time.

Outside this sparse report at Kiwiblog few details exist of what was actually said, but I congratulate Mr Gibbs for stating the bleeding obvious. The one-hundred-year experiment with central banks and their fiat money has failed spectacularly. Time to recognise that.

For anybody with eyes to see, the global financial and economic crisis –- more accurately called a monetary crisis -- should be the last straw for anyone who thinks that the government’s paper money leads to anything but instability.

You’ll be aware, for example, of the problems that importers and exporters and travellers have with rapidly changing foreign exchange rates – with the NZ dollar going up and down like a yoyo against other currencies our customers and suppliers trade in. The problem is created by a truckload of inconvertible paper currencies that are radically incommensurate with each other – a problem that the classical “gold coin” standard solves with what David Hume (who was a better economist than he was a philosopher) called the Price Specie Flow Mechanism, which renders the whole “balance of trade” problem nugatory.

You’re familiar with the vicious cycle that central-bank imposed interest rate increases have on a soaring New Zealand dollar – the state bank pushes up interest rates to “cool down” economic activity (activity that increases imports) which only attracts more hot money chasing the raised rates, pushing up the New Zealand dollar, making imports cheaper, meaning that interest rates are . . .

The problem is caused by a failed economic model that uses interest rates as a blunt instrument to steer markets where central planners want them to go—but that unintended consequences mean they never succeed in getting there.

You’ll know about the volatility of house prices and interest rates (the former because of the latter); about the blasé way that politicians world-wide have tried to solve their short-run economic problems by loading up the debt burden on future generations; about the loss of purchasing power of every dollar every year.

These problems, and many more, are solved with a gold standard.

Money backed by gold and precious metals has been around since trading first began, and the result has been centuries of stability. As a store of value and a bulwark of “price stability,” the precious metals are unsurpassed. “A small gold coin weighing approximately four grams—one-eighth of an ounce—and about the size of an American dime, appeared in various times and places as the French livre, Florentine florin, Spanish or Venetian ducat, Portuguese cruzado, dinar of the Muslim world, Byzantine bezant, or late-Roman solidus,” notes William Bernstein in his recent history of world trade. Factoring in increased productivity, all still buy roughly what could have been bought then. The daily wage of a semi-skilled worker for much of history was equivalent to a coin the same size in silver -- the Muslim dirham, the Greek drachma and the Roman denarius, for example. At current rates, this means the daily wage of a semi-skilled worker of the Roman era could buy around ninety-five dollars worth of goods. Compare this with the same semi-skilled worker of the early 1920s who was paid in paper money – money that is now worth around ninety-five times less than it was then.

But there are many myths about gold and the gold standard. I addressed a few on that Kiwiblog thread:

@ Luc Hansen, you said: ““There is not enough gold in the world to go back to the gold standard . . .”

Not so. There’s as much gold as you need. As Ludwig Von Mises points out in his book Human Action: “The quantity of money available in the whole economy is always sufficient to secure for everybody all that money does and can do.” [Frank Shostak explains what that means here.]@TVB, you said, “Gibbs does not seem to understand that international best practice on central banks having their main focus as controlling inflation is the best way to ensure currency stability . . . ”

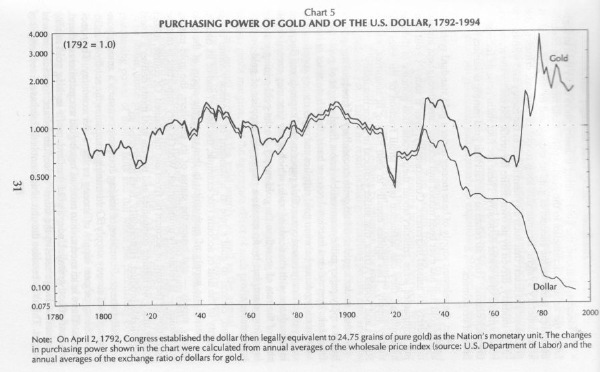

But since the rise of the central banks we’ve seen just the opposite. Just to quantify the instability somewhat, since the rise of the central banks, the loss of purchasing power caused by central bank meddling means that every dollar is worth around ninety-five times less than it did a century ago. By contrast, when the gold standard was at its height over the half-century to 1901, the purchasing power of every dollar actually increased. [See for example the two graphs at the foot of this post showing the currency stability of the gold standard period, contrasted with the massive loss of purchasing power since.]@Banana Llama, you said, “Forgive my ignorance but why would minting gold be any different than governments printing paper to shore up a deficit?”

The answer is in your own response: Since gold requires some significant labour to extract, smelt and mint, reality itself places a check on the ability of governments to use the destructive expedient of inflation (i.e., printing paper money) to bail themselves out. That a gold standard places a check on government’s ability to run deficits is not a problem of the gold standard, it is its primary virtue.

So a gold standard provides a check against inflation. Further, since gold (once produced) does not go away, then as long as fractional reserve banking is not contemplated, then there can never be any troubles with deflation either. After all, for that to happen it would mean that all the world’s stocks of one of nature’s basic elements would somehow have to disappear — a physical impossibility.@ Luc Hansen, you said: ““There is not enough gold in the world to go back to the gold standard . . .”

Well, there is — as I argue above. And it’s not beyond the wit of man to easily convert back to a stable currency unit based on gold. George Reisman, for one, indicates in this article how the remonetisation of gold can be very easily done: “Our Financial House of Cards and How to Start Replacing It With Solid Gold.”@Stephen, you asked: “And what of the possible ‘meddling’ of countries like South Africa et al?”

Well, the quantities involved just can’t match any “meddling” that countries like South Africa could do, even if they wanted to lose money by doing it. They achieve nothing by holding gold off the market. And the quantities involved mean they have no capacity to “dump” huge quantities onto the market.

World gold stocks are around 4500 million ounces, yet the top four producers, China, USA, South Africa, and Australia produce around only 7-10 million ounces each per year, and total gold production last year was only around 75 million ounces.

Hard to sway a market when you have so little traction with which to do it.

A look at the historical record tells you the story. From 1800 to 2000 the world’s gold stock increased from just over 100 million ounces to around 4000 million ounces. But at no time did gold production (as a year-on year percentage) exceed five percent; the yearly increments to the above-ground stock of gold have always small — much smaller than the yearly increments of paper money pumped out by over-zealous central banks.

Indeed, during the the period 1800-2000 the average year-on-year increase in the gold stock was just two percent. And as just one example among many, the peak years of production (the 1850s, when the Californian gold mines were coming on stream) saw the highest year-on-year increases ever, which was just 4.25 percent. Compare this to, for example, the increase each year of central bank paper, which in New Zealand (even since David Caygill’s’s ‘Reserve Bank Act’) has seen year-on-year increases every year of well over ten percent.

Says Richard Salsman, “As a result, gold’s real value — what it will purchase in goods and services — is the least variable of any commodity,” and is the reason the late Roy Jastram from Berkeley called this tendency for gold’s real value to be stable as “the golden constant.”

In fact, from 1550 to 2000 (the years that Jastram measured in his book The Golden Constant) the purchasing power of the pound was virtually stable for all that period, right until the First World War and the abandonment of the Gold Standard, when purchasing power started going through the floor.

The same story can be told of purchasing power of the US dollar from 1780 to the present, which is virtually stable from 1780 until the introduction of the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913, when once again the purchasing power goes down like a league player at summer training camp.

So in summary, there is very little ‘meddling’ with gold stocks that countries like South Africa can do, even if they wanted to. Whereas leaving central banks to print paper money positively invites destructive meddling – which has been precisely what we’ve seen over the last century.

A similar graph can be produced for New Zealand’s short history, which began in the middle of the classical gold standard (which lasted from 1815 to 1913).

![6a00d83451eb0069e200e55074d96c8833-800wi[3] 6a00d83451eb0069e200e55074d96c8833-800wi[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEimHKsiHlxWtJPrvR9FJeY9eygrReILOYfXbbnrsTH8gXtc2iDIfegUJwagTgivyEM1-qJTDjxuhDBevzDwOxoXVMz-h8OsPwpoicVirixLAknnesZDFQzWV-mk4ZBPo3g1hbaUWw/?imgmax=800)

UPDATE 2: Murray Rothbard succinctly explains the classical “gold coin” standard, which lasted from 1815 to 1914, in his excellent wee book What Has the Government Done to Our Money.

The Classical Gold Standard, 1815-1914

We can look back upon the "classical" gold standard, the Western world of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the literal and metaphorical Golden Age. With the exception of the troublesome problem of silver, the world was on a gold standard, which meant that each national currency (the dollar, pound, franc, etc.) was merely a name for a certain definite weight of gold. The "dollar," for example, was defined as 1/20 of a gold ounce, the pound sterling as slightly less than 1/4 of a gold ounce, and so on. This meant that the "exchange rates" between the various national currencies were fixed, not because they were arbitrarily controlled by government, but in the same way that one pound of weight is defined as being equal to sixteen ounces.

The international gold standard meant that the benefits of having one money medium were extended throughout the world. One of the reasons for the growth and prosperity of the United States has been the fact that we have enjoyed one money throughout the large area of the country. We have had a gold or at least a single dollar standard with the entire country, and did not have to suffer the chaos of each city and county issuing its own money which would then fluctuate with respect to the moneys of all the other cities and counties. The nineteenth century saw the benefits of one money throughout the civilized world. One money facilitated freedom of trade, investment, and travel throughout that trading and monetary area, with the consequent growth of specialization and the international division of labor.

It must be emphasized that gold was not selected arbitrarily by governments to be the monetary standard. Gold had developed for many centuries on the free market as the best money; as the commodity providing the most stable and desirable monetary medium. Above all, the supply and provision of gold was subject only to market forces, and not to the arbitrary printing press of the government.

The international gold standard provided an automatic market mechanism for checking the inflationary potential of government. It also provide an automatic mechanism for keeping the balance of payments of each country in equilibrium. As the philosopher and economist David Hume pointed out in the mid-eighteenth century, if one nation, say France, inflates its supply of paper francs, its prices rise; the increasing incomes in paper francs stimulates imports from abroad, which are also spurred by the fact that prices of imports are now relatively cheaper than prices at home. At the same time, the higher prices at home discourage exports abroad; the result is a deficit in the balance of payments, which must be paid for by foreign countries cashing in francs for gold. The gold outflow means that France must eventually contract its inflated paper francs in order to prevent a loss of all of its gold. If the inflation has taken the form of bank deposits, then the French banks have to contract their loans and deposits in order to avoid bankruptcy as foreigners call upon the French banks to redeem their deposits in gold. The contraction lowers prices at home, and generates an export surplus, thereby reversing the gold outflow, until the price levels are equalized in France and in other countries as well.

It is true that the interventions of governments previous to the nineteenth century weakened the speed of this market mechanism, and allowed for a business cycle of inflation and recession within this gold standard framework. These interventions were particularly: the governments' monopolizing of the mint, legal tender laws, the creation of paper money, and the development of inflationary banking propelled by each of the governments. But while these interventions slowed the adjustments of the market, these adjustments were still in ultimate control of the situation. So while the classical gold standard of the nineteenth century was not perfect, and allowed for relatively minor booms and busts, it still provided us with by far the best monetary order the world has ever known, an order which worked, which kept business cycles from getting out of hand, and which enabled the development of free international trade, exchange, and investment.

So why did the classical “gold coin” standard collapse? Answer: it didn’t.

“The gold standard was the world standard of the age of capitalism, increasing welfare, liberty, and democracy, both political and economic. . . All those intent upon sabotaging the evolution toward welfare, peace, freedom, and democracy loathed the gold standard, and not only on account of its economic significance.’

- Ludwig Von Mises (Human Action)“It was not gold that failed; it was the folly of trusting government to keep its promises. To wage the catastrophic war of Word War I, each government had to inflate its ow supply of paper and bank currency. So sever was this inflation that it was impossible for the warring nations to keep their pledges, and so they went ‘off the gold standard,’ i.e., declared their bankruptcy. . .”

- Murray Rothbard (What Has the Government Done to Our Money.)“The gold standard did not collapse. Governments abolished it in order to pave the way for inflation. The whole grim apparatus of oppression and coercion, policemen, customs guards, penal courts, prisons, in some countries even executioners, had to be put into action in order to destroy the gold standard.”

- Ludwig Von Mises (The Theory of Money & Credit)

And to return to gold?

“The return to gold does not depend on the fulfillment of some material condition. It is an ideological problem. It presupposes only one thing: the abandonment of the illusion that increasing the quantity of money creates prosperity.”

- Ludwig Von Mises (‘Economic Freedom and Interventionism’)

4 comments:

While I agree that the current "global financial crisis" is actually a government created monetary crisis, I don't understand what is so special about gold. It is just another commodity and you might as well link currency values to platinum, uranium or cows. Individual traders can today hedge to gold if they want to, thereby protecting themselves against the fickle government central bankers (if gold does indeed do that). A better solution, perhaps, is to abolish national currencies and return to private money. Then peoploe will have the freedom to choose to trade in whichever dollar is the most reliable form of exchange.

@Kiwiwit. "It is just another commodity and you might as well link currency values to platinum, uranium or cows."

With a commodity standard for money, it's not that currency values are "linked" to the commodity. The commodity essentially is the currency. Banknotes are essentially just "warehouse receipts" that make transactions in the commodity/currency easier.

And over history many commodities have been chosen as the means by which trade exchanges can be made, including cows, and potentially in the future uranium and platinum (though using uranium as your currency would give new meaning to the phrase "burning a hole in my pocket.")

But there was good reason to choose gold, and good reasons to continue doing so.

Carl Menger's seminal account of the origin of money explains most of them.

"Individual traders can today hedge to gold if they want to . . . "

Though the chief problem with this is that the government's paper money is still mandated as "legal tender." And as Gresham's law reminds us, bad money [overvalued by law] drives out good.

Which means until legal tender laws are overturned, gold can be merely a background commodity instead of backstop.

So on that point I agree with your last point: that the main job is to denationationalise money.

"Individual traders can today hedge to gold if they want to . . . "

This assumes traders are able to actually take physical possession of the gold they are supposedly trading. If not, then they are resorting to blind trust in pieces of paper backed by promises. Sound familiar....?

Anyway, I suspect that a lot of the gold trading presently ocurring is not physically backed by anything real. The fun and learning could really start if enough traders insist on being delivered their gold, only to find they can't get it. I wonder if the repositories have really got sufficient gold stored to correspond with what is represented to be present.

LGM

To answer Kiwiwit:

A return to the gold standard would be only a temporary, transitionary measure. After a reasonably stable gold currency had replaced fiat money, a truly free market in money could come into existence. I.e. legal tender laws would be repealed AND any kind of tax on the appreciation of commodities would cease to exist.

I personally believe that most people would choose to use gold as the main currency. However, I do expect that many other commodities (such as silver, platinum etc) would be used at some times/places.

Commodities do spontaneously become used as money. In recent times, bottled water, cigarettes and livestock have been used in some countries where the national currency has broken down.

Also, it is possible for commerce to function with more than one currency. Go to many tourist centres, and you will notice that many shops/vendors accept more than one currency. For example, when I visited Vanuatu, they accepted Vatu, USD and AUD in many Port Vila shops. This means that it would be possible for gold, silver etc to coexist as currencies.

Furthermore, it would be possible to use gold even for small transactions. You would merely use a bank note for any amount of gold, redeemable at the bank of issue (ultimately, if the bank were trustworthy, you could redeem it at other banks).

Post a Comment