Guest post by Kris Sayce of Money Morning Australia

![_Kris_Sayce_headshot_thumb[2] _Kris_Sayce_headshot_thumb[2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgNdFOVk7zs1hwCZC8lcDTr3dHKdlQsLipYfink81zMJgh2U7nDDlV3zFMCi4og6o5LR3GZoY2eWoR2hHmMQdUJ6ea1dOsEvoAW7w67f8hk8mIsyqLGmJ0-avGaabuh-OG1oNq2/?imgmax=800)

The biggie could be just about to hit the fan.

Not the real big one – the United States. But one of the other big ones, the UK.

According to ratings agency Fitch:

The scale of the UK’s fiscal challenge is formidable and warrants a faster pace of medium term deficit reduction than set out in the April 2010 Budget. The rise in public debt ratios since 2008 is faster than for any other ‘AAA’?rated sovereign and the primary balance adjustment required to stabilise debt is amongst the highest of advanced countries. The primary deficit is nearly twice as large as that seen in previous episodes of fiscal deterioration in the UK in the 1970s and early 1990s.”

Oh dear.

And if you look at the chart below from Fitch, you’ll see that the UK is keeping pretty bad company:

Click to enlarge . [And for reference, New Zealand’s figure is 13 %, according to Bill English, placing us between Cyprus and Italy.]

There’s no getting around it, the UK economy is in big trouble.

You can see how big, by looking at a few of the figures compiled by Fitch.

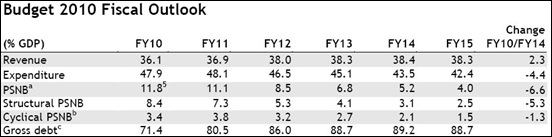

Take a look at these numbers showing the state of the UK government budget expressed as a percentage of GDP:

Click to enlarge. Source: Fitch Ratings. [For reference, according to the OECD, New Zealand govt spending as a percentage of GDP is 43%. Its tax-take is 40%]

It’s pretty unbelievable to begin with that the UK government takes 36.1% of the economy’s GDP in taxation. A number forecast to rise to 38.3% by 2015.

But worse than that is the expenditure. Not content with taxing too much, the UK government has been spending a lot more than it takes in taxes. The expenditure accounts for a massive 47.9% of GDP.

In other words, nearly 50 pence of every pound spent in the UK economy is spent by the government.

No wonder it’s in such a mess. And with gross debt estimated to reach 89.2% of GDP by 2014 UK taxpayers appear destined to have a government debt albatross around their neck for many, many years to come.

And what does the new Conservative and Liberal Democrat (ConDem as it’s been labelled) propose to do about it?

[Hehem] It plans on cutting spending by GBP6.24 billion. It sounds a lot, but when you put it another way, it’s just a puny 0.4% of GDP.

Makes you wonder why they’re even bothering.

And considering one of the biggest expenses to the UK government is the untouchable National Health Service (NHS), which cost the UK taxpayer GBP92.5 billion in 2009, it’s hard to see how the government can either cut spending or pay down the national debt…

Unless it inflates its way out of trouble.

Which of course it has already tried to do with the so-called quantitative easing policy implemented by the Bank of England.

But it’s not just public sector debt that’s crippling the UK. The whole rotten economy is at it.

Our pals over at Wikipedia have compiled this table showing total external (public + private) debt per country:

Click to enlarge. [For reference, the per capita debt for New Zealand is $13,636 per capita, which as a percentage of GDP is 50%]

The UK is second only to the United States in debt owed to foreigners. A whacking great USD$9 trillion of debt, or amazingly, 416% of GDP, or a USD$147,060 per person!

You’ll notice Australia puts in an appearance with USD920 billion, or 92% of GDP.

And globally the debt figure stands at USD$56.9 trillion, which is only just less than the entire global GDP of USD$61.1 trillion:

Look, when you’re dealing with numbers this big it almost becomes incomprehensible. After all, many will argue that it doesn’t matter what the size of the debt is, but rather the ability to service it.

We’ve heard that argument plenty of times recently. It’s been applied to companies, to property buyers and investors, and also to individual countries.

The thing is, the size of the debt does matter. The argument about it being about the serviceability of the debt is just a smokescreen. In fact, you only ever hear someone talk about the serviceability of debt when they or the institution they’re talking about is in too much debt.

The total debt matters because that is the amount owed to the creditor, plain and simple.

The debt must eventually be repaid. Arguing that the size of the repayments is all that matters just doesn’t make sense. Besides, it encourages and leads to ever larger debt levels, which is what we’ve seen the world over.

Think of it this way. If you lend a mate $20,000 and he agrees to pay you back $100 per week over 4 years then you might be happy with that. He’s a mate and you’re sure he’s good for it.

But then in a year’s time when he still owes you $15,000 he asks you for another $20,000 for which he’ll pay you another $100 per week, you might think, “Hang on, that’s 35 grand I’m lending here…”

And then another year passes and he wants another $20,000… and so on.

At some point, as a creditor you’re gonna start to get concerned about whether and when you’re going to get your money back. Because all you’ve done so far is lend out money. You’ve received the weekly repayments but somehow you’ve got less money in the bank because you’ve continued to lend it out.

And of course, you don’t know how much your mate is borrowing from someone else either. Can he really afford to pay you back? Where’s he going to get the money from?

You soon figure out that you’re getting a raw deal, and there’s no guarantee you’ll ever be repaid.

It’s the same, but on a much bigger scale in international finance. Creditors are lending money out getting repayments in return, but the principal is never actually repaid. Refinancing or new borrowings are just added on to the old debt and the repayments just get bigger.

At some point it breaks down. Not just because of the serviceability of the debt, but rather because creditors realise they’ve been stitched up.

They want their money back or they want better terms – i.e., Higher interest rates. Or both!

Think about it. Greece was more than able to service its debt. But only so long as creditors continued to lend it more money to pay for it. As soon as creditors started to ask questions and get toey then the whole thing fell apart.

You see, it’s vendor financing on a massive scale, “Here’s a billion dollars so you can pay back the billion dollars you owe us. Now you owe us a billion dollars.”

That can’t last forever. It’s absolute madness and it’s unsustainable.

Yet the idea of serviceability of debts is gaining more traction among the mainstream drones. We witnessed the excitement on CNBC a couple of weeks ago when Erin Burnett and Jim Cramer went bonkers after figuring out the US debt costs were less today than they were two years ago, even though the debt is larger.

Why? Because interest rates are lower. The size of the debt doesn’t matter, it’s the ability to service the debt, was their claim.

But this is what happens when you have a central bank manipulating the interest rate. Luring investors and speculators in with sweet smelling cheap money.

However, the endgame won’t be so sweet when creditors decide they want their money back, want a higher rate of interest, and/or they realise cash is being devalued at such a fast rate that they no longer see any value in it or in lending it, but instead prefer real assets.

That’s the point at which inflation gets out of control. As individuals and investors seek to dispose of cash as quickly as possible in exchange for something tangible.

And don’t for a moment think that it can’t happen because thanks to the central bankers, bankers and governments, it’s destined to happen.

So next time someone tells you it’s the ability to service the debt not the size of the debt, don’t believe them.

Cheers,

Kris.

4 comments:

Interesting post - I saw a graph the other day which showed India as having huge Govt debt so another at risk country.

My view is that debt is fine when you are starting out as a country and building your infrastructure etc. Once you are an "established" (or grown up) country you should not have any Govt debt - you should be able to pay for what you want to spent from taxes/income from savings.

I consider NZ to be a mature economy so I would like to see a nil Govt debt position as a KPI going forward. Means we would have to do something about paying back the debt which is kind of the point of the post.

Kevin

I would actually be interested to know who all that debt is actually owed to. Who are the creditors that can come knocking? Is it actually a zero-sum game? I would assume that changes in exchange rates may distort the actual sums borrowed vs those required to be paid-back.

"I would actually be interested to know who all that debt is actually owed to?"

In the end, in a word:

Savers.

Because in the end -- despite all the manipulations by central banks and governments; the printing of bonds by Treasury, for example, which the Reserve Bank prints money to buy; or the credit creation by private banks to buy the bonds that the Reserve Bank wouldn't -- real resources have been transferred from the pool of real savings to those who wouldn't or couldn't save.

And those resources will have to be re-created again at some time in some way by someone. Or by a lot of someones.

That's what Ludwig Von Mises meant when he said that you pay for a war [or a stimulus plan] today; in that however long a loan period you might set the loan for (pretending to yourself that it's your grandchildren who will pay), or however much rhetoric you might spin to the contrary (telling ourselves it's okay in the long run because we owe it to ourselves anyway) it's the resources saved up yesterday that pay for the government borrowing of today. Resources that would or could or should have been used for productive ends, to make us all wealthier tomorrow, but that instead have been consumed today by the welfare state, and by the slow economic suicide of stimulunacy.

Peter- First you are praising bureaucrats now you are missing a fundamental point. Hungover or getting old? ;^)

The global debt is not owed to anyone off planet. For every borrower there is a lender. It really is a zero sum game with inflation working in favour of the borrowers.

Borrowing is ALWAYS against future cashflow. Using that money to develop resources is perfectly legitimate. Using it for current consumption we both agree is not.

Global GDP is about equal to debt. A homeowner can handle debt about 3 times income. Globally debt levels seem reasonable to me. There are certainly country level imbalances.

This is a relevant and interesting post. I think part of the UK external debt is a reflection of its role as a global financial centre.

Certainly it has problems but the government has had only a few weeks to start reviewing the books and will release an emergency budget in the coming weeks. I think you will see some more fundamental cuts at that point. £6bn is just a start.

Post a Comment