Another six cans of whip-arse from the ice-cold vaults of NOT PC …

* * * *

Friday, January 26, 2007

Saving the planet? Who do you call?

There's an interesting point made here at CapMag that warmists and environmentalists might want to consider. Environmentalists have said for years that "we" need to create "alternative" forms of energy. But how have "they" gone about creating them?

“Well, they support like-minded politicians -- who've invented nothing but obstacles to innovation. They march in protests -- that have created nothing but vandalism. And they rage against capitalism -- the only system by which worthy creations can effectively be financed, marketed and widely distributed... Clearly, a viable, cleaner form of energy (if you buy into the faulty premise that one is needed) will not be created by some snarling rock-hurler, nor some land-confiscating government official, nor some loafer who nests with squirrels.”Innovation cannot be forced, and nor can it be created by political edict.

So if “alternative energies” and viable recycling schemes and the like are every going to emerge, they'll only do so if there's real and genuine demand for them.

And no one knows either where or with whom creation will happen—all we can do is leave people free to create. If they're going to come from anywhere, they'll come from the same place that all innovations have come from -- from the brain of a creator -- and that creation can neither be forced nor subsidised.

And here’s something else we know: that when (or if) they’re produced, they'll be produced and distributed by the very profit-oriented capitalist system that too many environmentalists profess to despise, and even while the creators and distributors are being shackled by controls and regulations dreamed up the loafers and rock-hurlers and government officials.

So ironically, as CapMag summarises, "it's the profit-oriented, productive achiever-types that the 'save the planet' crowd most despise and desire to shackle" who are the ones the 'save the planet' crowd most need.

“The men and women who possess the ingenuity, personal ambition, and business acumen that a successful new energy venture would require, environmentalists lob eggs at. Yet it's businesspeople, not "Friends of the Earth," who, by translating scientific discoveries into practical reality, actually advance human life and eliminate pollution.”Give it some thought.

If you're still not convinced by Beer O'Clock-time this afternoon, then ponder the author's concluding thought:

“If the planet truly did require ecological salvation (and there's plenty of evidence indicating it doesn't), ask yourself who'd be more apt to achieve a solution: one million bureaucrats or ‘Earth First!’ members compelled by their ‘love for nature’? Or one creative genius of the caliber of Bill Gates or Henry Ford driven by the profit-motive? You know the answer.”

LINK: Environmentalism vs creativity - Wayne Dunn, Capitalism Magazine

* * * * *

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Where's my free will?

Tell that to Thomas Jefferson. Or Nelson Mandela.

But such is the incredulity of the determinist conclusion: that between them nature and nurture determine human behaviour, so humans themselves should be neither praised nor condemned.

Sounds like horse shit to me. But then, according to Edwards et al they have no choice about shovelling shit—and nor do you about taking it.

So much for the nonsense of “hard determinism.”

In the words of Ayn Rand, the determinist argument—that you’re neither to be blamed nor lauded for your behaviour—is simply “an alibi for weaklings.”

“Don't excuse depravity. Don't drool over weaklings as conditioned "victims of circumstances’ (or of ‘background’ or of ‘society’), who ‘couldn't help it.’ You are actually providing an excuse and an alibi for the worst instincts in the weakest members of your audience. . .

“. . . the best advice I can give you is never to regard yourself as a product of your environment. That is not the key to me, to you, or to any human being. It is not a key to anything, it is merely an alibi for weaklings.”

Building on Ayn Rand’s observations on free will and the failures of the determinism, philosopher Tibor Machan points out that the determinist argument utterly ignores free will—the faculty that allows us to make decisions for ourselves. It is this faculty, he says, that truly determines our character .

While nature and nurture certainly play a part in forming our talents and personality, he argues, what we do with what we’re given is up to us. It’s up to our free will-and the choices we make.

In his argument, nature and nurture build our personality, but using our free will builds our character.

But where does our free will come from? Where does it reside? How does it work? To answer you, we’re going to have to go back to bed. . .

THE FIRST THING YOU NOTICE through the fog of sleep is a loud, ringing sound. As you rise up through the fog of sleep you recognise it as an alarm of some sort. Your alarm clock. You focus further and realise that it's not going to turn itself off. As you force yourself awake you direct your focus to your limbs, lifting yourself out of bed, and you turn off the clock on your way to the bathroom, making yourself shake the sleep from your mind as you go. It's the start of another day.

As you shower, you set yourself thinking about what you need to do today and, as you do and as you shower, the scales of sleep slip ever further away. You understand you have an important day ahead, and you feel yourself rising up to meet it. You choose to. In a few short minutes, by your own direction, your mind has changed from an inert unconscious thing, one barely able to grasp what's going on around it, to one that is now focussed upon the events of the day and is starting to make plans to meet them ... and all this even before the first coffee!

Most of us manage this process in a few minutes. Some take hours. Some will choose to stay unfocussed for days. But everyone who has ever experienced this -- which is all of us, at some time – even Brian Edwards and his criminals--has experienced what it is to have free will.

Free will at its root is that process of choosing to focus, of deciding first of all to lift our level of awareness from a lower level to a higher one (or to decide not to), and then directing our focussed attention to something on which we've determined we need to pay attention. A lecture perhaps. Our alarm clock. A book. A piece of music. A blog post on free will. Someone offering us a beer. At each stage of listening, reading, comprehending, trying to grasp a thought (as Vermeer's Geographer is doing in the picture above) we can choose to maintain attention and focus on what we're trying to take in, to weigh the thoughts and melodies and information that is coming in, or we can choose to float off in a vague fog and let everything just wash over us.

The process of turning off our alarm clock and heading into a lecture shows the process in microcosm: choosing to focus more intensely at each new level of awareness we reach. From the fog of sleep right up to the intense awareness needed to focus on your lecturer (and spot her errors) every step of the way we’re choosing to focus more intensely.

And even if we choose not to, we still have made a choice.

The act of choosing to pay attention (or not to) is a volitionally focussed act by which we first say to ourselves, "I need to focus on this, to understand this," and then acting -- choosing to act -- so as to direct our minds to that on which we ourselves have determined that we need to understand.

Observe your own mind while you’re reading this post. Are you focussing on the arguments in an attempt to understand and address them, or have you already drifted off into non-comprehension and evasion?

As I've described above, the act of focussing is voluntary, and is almost like continually turning on a car. At each stage we can choose to go either to a higher level of awareness, or not; we can choose to focus, or we can choose to drift back off either to sleep, or into a state of unfocussed lethargy. You can lead a horse to water but you can't make it drink. Equally, you can lead someone else's brain to stimulus, but you can't make it respond. That person must do that work for themselves.

Volition is a powerful factor. Thoughts, values, principles aren’t just given to us out of the ether, or imprinted upon us by our genes; rather, they are things to identify and think about and grasp for ourselves. Or not. No one can do the thinking for someone else. With sufficient will we can work towards grasping the highest concepts open to us, or we can even sleep through the warning alarm clocks of our consciousness.

That choice -- to focus or not; to switch on or not -- is contained entirely within ourselves, and from that choice made by each of us every minute of every day all human thought and all human action is the result. The fact that we are continually making this choice (or choosing not make it) every waking minute of every working day is perhaps why we sometimes fail to see that we're doing it. We've almost automatised our awareness of it, but honest introspection (if we honestly choose to do so) is all it requires to be identified.

This is the nature of the volitional consciousness that each of us does possess, even Brian Edwards, and is the fact those who choose to deny free will wish to evade: that this great thinking engine resting on top of our shoulders does not turn itself on automatically. We ourselves own the keys to the engine, and it is in that fundamental choice -- to think, or not to think; to focus, or not to focus; to go to a higher level of awareness, or to drift in and out of awareness -- that the faculty of free will itself resides.

So given that very brief discussion of free will -- to which, if you like, you can add previous similar discussions here, here, here, here and here -- what then do you make of this discussion from the former Sir Humphrey's blog. Where does free will come from? From her God, says Lucyna.

Where does this thing called free will come from?

"...if there is no God there’s no free will because we are completely phenomena of matter... we cannot be considered morally responsible beings unless we have free will. We do everything because we are controlled by our genes or our environment."

- comments by David Quinn in The God Delusion: David Quinn & Richard Dawkins debateLogically, if you are an atheist, you will believe that we are completely influenced by our genetics and environment. That there is no free-will, that moral responsibility has no ability to manifest in any human being. If you don't believe all of that, then you cannot be an atheist and you must have some inkling that God exists.

What do you make of that then? Let’s turn on our brains ourselves and examine it. "If there's no God then there's no free will"? And “If you are an atheist” then “logically” [logically?] you can't "believe" in free will?

Doesn’t this sound like horse shit too?

As I've suggested above, we don't need to "believe" in free will in the same way a Christian chooses to “believe” in the existence of a supernatural being; instead, to identify that we do have the faculty of free will all we have to do is introspect—to apply our cognition inwards (to choose to) and watch ourselves making choices. (Indeed, you can do it right now as you weigh in your mind that last thought, and choose whether or not to accept it -- or whether to evade the effort or the knowledge. And recognise, dear reader, that if you choose not to accept it or to evade it, you've still made a choice.)

So much for needing to believe in the supernatural in order to "believe" in free will. As Ayn Rand identified:

“That which you call your soul or your spirit is your consciousness, and that which you call your "free will" is your mind's freedom to think or not, the only will you have, your only freedom, the choice that controls all the choices you make and determines your life and your character.”

We have consciousness. Consciousness is endowed by its nature with the faculty of free will. What we each choose to do with our own consciousness is up to us -- and it's there that the discussion of morality really begins...

LINKS: Nature v Nurture: Character is all - Not PC

The chemistry of love - Not PC

The fatalism of entropy. The dynamism of spontaneous order - Not PC

More on value judgements in art - Not PC

Excusing the 'bash' - Not PC

Man and free will - Lucyna, Sir Humphrey's

RELATED: Philosophy, Ethics, Religion

* * * * *

Sunday, January 13, 2008

If God is dead ... rejoice (updated)

Elizabeth Anderson’s “If God is Dead” essay is one of the best indictments of The Bible that novelist Ed Cline has ever read, he says: “Posing the conundrum of why God (or Allah, or whomever) is considered to be the be-all and end-all of morality – originating morality and rewarding it and punishing its delinquency – she writes:

“ ‘Consider first God’s moral character, as revealed in the Bible. He routinely punishes people for the sins of others. He punishes all mothers by condemning them to painful childbirth, for Eve’s sin. He punishes all human beings by condemning them to labor, for Adam’s sin (Gen. 3:16-18). He regrets his creation, and in a fit of pique, commits genocide and ecocide by flooding the earth (Gen. 6:7). He hardens Pharaoh’s heart against freeing the Israelites (Ex. 7:3), so as to provide the occasion for visiting plagues upon the Egyptians, who, as helpless subjects of a tyrant, had no part in Pharaoh’s decision. (So much for respecting free will, the standard justification for the existence of evil in the world.)’ ”

So even if you believed the existence of this supernatural monster, why would you grant him any authority at all over morality? It just makes no sense at all.

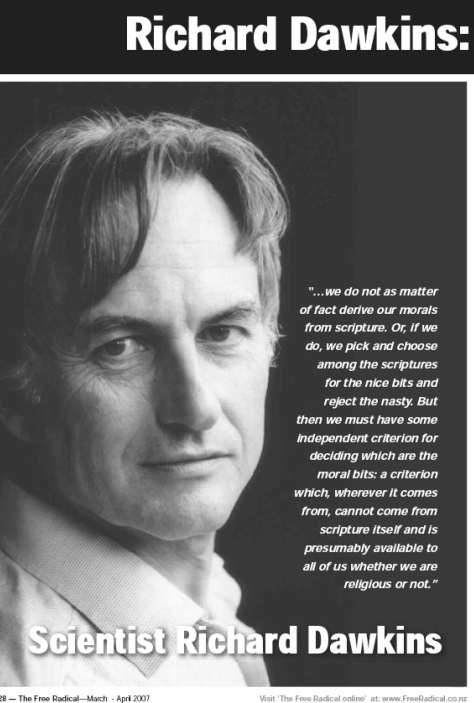

UPDATE: Fact is, even Christians don't take their morality from The Bible, a point made perfectly clearly by Mr Dawkins:

It’s true that we have some independent basis for deciding on good and bad, dut that doesn't mean that the source of morality is somehow "innate," which is where (despite all their other good work) Team Dawkins get it wrong. Team Dawkins suggest that we “jes’ know” what’s right or wrong, that our gut feelings just tell us so.

And yet other will tell you that morality is determined by law or by politics, or by your social group or culture.

This too is horse shit—all of it. The source of morality is neither God or Helen Clark; neither our neighbours nor our own gut feelings. No, the source of morality is reality—and I’ll explain in a moment what that means.

But first, a brief advertisement for reading on.

First of all, it involves beer—which should be motivation enough. And second of all, we get to smack the religious right.

It should be obvious enough why this matters, but to those who eschew thinking about ethics and who prefer instead to bloviate solely about politics, there is a political connection here which Peter Schwarz points out:

“Does morality depend upon religion? Most people believe it does, which is a major reason behind the appeal of the religious right. People believe that without faith in a supernatural authority, we can have no moral values--no moral absolutes, no black-and-white distinctions, no firm demarcation between good and evil--in life or in politics. This is the assumption underlying Justice Antonin Scalia's recent assertion that "government derives its authority from God," since only religious faith can supposedly provide moral constraints on human action.

“And what draws people to this bizarre premise--the premise [of the likes of Brian Edwards]that there is no rational basis for refraining from murder, rape or anarchism? The left's persistent assault on moral values.

“That is, liberals characteristically renounce moral absolutes in favor of moral grayness.”

BUT MORALITY ISN'T GREY. It is absolute. It's absolute because the source of morality is reality, which is impossible for anyone to evade--even the most hard-bitten religionist.

Fact is, there are serious problems with the approaches taken by both the religionists (who insist on intrinsic rules, yet insist again on cherrypicking which ones are really and truly the ones to live by), and by their subjectivist opponents (who insist there are no absolutes, except the rule that there are no absolutes).

But to dismiss these objections is not to answer our question here, which is: “Can you then have morality without God? Whence comes moral structure if the Law-Giver in Chief is dead?”. The answer, to say it once again, is reality, and the constraints it places up on us. The source and locus of all our values is reality. Where else could they come from?

Contra David Hume, All facts, to us, are potentially value-laden. The world is fashioned in a particular way, and to derive happiness and flourishing in such a world we need to act in such and such a way.

In response to this all too obvious point, those trained in university philosophy departments will often wheel out something called the 'Is-Ought' argument as 'proof' that facts are inherently value-free, or (to put it another way), that neither reality nor reason provide any basis from which to formulate a reliable ethics.

THE 'IS-OUGHT' ARGUMENT was a remarkable piece of sophistry devised by a drinker called David Hume (as many of you will remember, "David Hume could out-consume Schopenhauer and Schlegel" ), who suggested between drinks that the fact that the world is this way or that way provides no means of suggesting whether one ought or ought not do something, and thus there is no way -- no way at all -- to put together any sort of rational morality. This is the sort of thing that in university philosophy departments passes for a sophisticated argument.

What's remarkable is that such a fatuous proposition should still have sufficient legs to persuade graduates of philosophy departments over two-hundred years after it was formulated. The 'is-ought problem' is a problem only if your mind has been crippled by such a department.

Aristotle stands first in line as a healthy contrast to both religionists and subjectivists and university philosophy professors in being a consistent (and too-frequently overlooked) advocate of a rational, earthly morality -- his was a "teleological" approach to ethics. That is, he said, we each act to achieve certain ends, and those ends must be the furtherance of our lives. All actions are (or should be) done "for the sake of" achieving some goal.

ARISTTOTLE PROVIDES A STARTING point from which to proceed rationally. Let’s think about what the basis for any rational standard of morality for human life would be. Morality should be ends-based – it should be goal-directed – but what end should it pursue? Surely the starting point would be the nature of human life itself? Shouldn’t the fact that human beings do have a specific nature tell us what we ought to do?

IT WAS AYN RAND who identified that the crucial fact about human life that provides such a starting point is the conditional nature of life, the fact that living beings daily confront the ever-present alternative of life or death. Act in this way and our life is sustained. Act in that way, and it isn't. Life is not automatic; it requires effort to sustain it, and reason to ascertain what leads towards death (which is bad), and what leads towards life (which is good). What standard then provides the basis by which a rational morality judges what one ought to do, or ought not to do? Life itself. Life is the standard. As Ayn Rand observed in her essay ‘The Objectivist Ethics,’

“It is only the concept of "Life" that makes the concept of "Value" possible. It is only to a living entity that things can be good or evil.”

Following Rand, Greg Salmieri and Alan Gotthelf point out that,

“Rand’s virtue-focused rational egoism differs from traditional [ie., Aristotelian] eudaimonism in that Rand regards ethics as an exact science. Rather than deriving her virtues from a vaguely defined human function, she takes “Man’s Life” – i.e. that which is required for the survival of a rational animal across its lifespan – as her standard of value. This accounts for the nobility she ascribes to production – “the application of reason to the problem of survival” (1966, p. 9). For Rand, reason is man’s means of survival, and even the most theoretical and spiritual functions – science, philosophy, art, love, and reverence for the human potential, among others – are for the sake of life-sustaining action. This, for her, does not demean the spiritual by “bringing it down” to the level of the material; rather, it elevates the material and grounds the spiritual.”

THE FACT THAT LIFE is conditional tells us what we ought to do: in the most basic sense, if we wish to sustain our life, then we ought to act in a certain way. This is the starting point for a rational, reality-based ethics: reality itself.

If that glass of brown liquid in front before us is dangerously toxic, then one ought not drink it. That would be bad. If, however, it is a glass of Epic Pale Ale, Limburg Czechmate or Stonecutter Renaissance Scotch Ale, then all things being equal one ought to consume it -- and with gusto. That would be good.

So much for the 'is-ought problem.' The fact that reality is constituted in a certain way, and that every living being confronts the fundamental existential alternative of life or death is what provides the basic level of guidance as to what one ought or ought not do. This fundamental alternative highlights an immutable fact of nature, which is that everything that is alive must act in its self-interest or die. A lion must hunt or starve. A deer must run from the hunter or be eaten. Man must obtain food and shelter, or perish. We ought to seek out good beer or else sentence ourselves to a lifetime of drinking Tui.

The pursuit of morality is that important.

The fact that we exist possessing a specific nature and that reality is constituted the way it is tells us what we ought to do.

(The intelligent reader will already have noticed that in seeing morality in this way, the primary issue in morality is not our responsibility to others, but fundamentally our responsibility to ourselves. Without first understanding our responsibility for sustaining our own life, no other responsibilities or obligations are even possible. Tibor Machan observes that this fact is recognised even in airline travel, where the instruction is always given that if oxygen masks drop from the ceiling you should put your own on first before trying to help others. Basically, this is a recognition that if you don't look after yourself first then you're dead, and of no use either to anyone else or to yourself. This might help explain to interested readers why Ayn Rand named her work on ethics: The Virtue of Selfishness.)

So to any living being alert enough to notice it, facts are not inherently value-free, they are value-laden – some facts are harmful and we should act to avoid them; others are likely to be so pleasant that we should act to embrace them -- but all facts we should seek to understand, and in this context we should understand that all facts are potentially of either value or disvalue to us. Facts are inherently value-laden.

Contemplating the delightful reality of a glass of Limburg Czechmate, for example, demonstrates that some facts can be very desirable indeed, and are very much worth embracing. The point here is that it is not the facts themselves that make them valuable, it is our own relationship to those facts: how those facts impinge upon and affect our lives for either good or ill. It is up to us to discover and to make the most of these values. Leonard Peikoff makes the point in his book Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand:

“Sunlight, tidal waves, the law of gravity, et al. are not good or bad; they simply are; such facts constitute reality and are thus the basis of all value-judgments. This does not, however, alter the principle that every "is" implies an "ought." The reason is that every fact of reality which we discover has, directly or indirectly, an implication for man's self-preservation and thus for his proper course of action. In relation to the goal of staying alive, the fact demands specific kinds of actions and prohibits others; i.e., it entails a definite set of evaluations.

“For instance, sunlight is a fact of metaphysical reality; but once its effects are discovered by man and integrated to his goals, a long series of evaluations follows: the sun is a good thing (an essential of life as we know it); i.e., within the appropriate limits, its light and heat are good, good for us; other things being equal, therefore, we ought to plant our crops in certain locations, build our homes in a certain way (with windows), and so forth; beyond the appropriate limits, however, sunlight is not good (it causes burns or skin cancer); etc. All these evaluations are demanded by the cognitions involved -- if one pursues knowledge in order to guide one's actions. Similarly, tidal waves are bad, even though natural; they are bad for us if we get caught in one, and we ought to do whatever we can to avoid such a fate. Even the knowledge of the law of gravity, which represents a somewhat different kind of example, entails a host of evaluations --among the most obvious of which are: using a parachute in midair is good, and jumping out of a plane without one is bad, bad for a man's life.”

But this is (or should be) basic stuff.

NOW, UNLESS YOU'RE a university philosophy professor (or David Hume) you don't simply sit there looking wide-eyed at the world, acting only on the basis of what appears in front of you on the bar. As Aristotle pointed out, if we want the good then our actions should be goal-directed. A rational man acts with purpose: that is, he acts in pursuit of his values. If our purpose is the enjoyment of more glasses of Limburg Czechmate, for example, (something even David Hume would agree is a value) then we must act in a way that allows us to acquire more drinking vouchers with which to buy them, a fridge in which to keep them, and to sustain our health, wealth and happiness so that we might enjoy them for many more years in the future.

We should act in this way or in that way, in other words, in order to bring into reality certain facts that our (rationally-derived) values tell us are good. Acting in this way is itself good. We might even call it “virtuous” – virtues being the means by which we acquire our values.

And further: we should act not just in order to stay alive. As Aristotle and Rand both point out, the proper human state of life is not just bare survival, it is a state of flourishing – not just life, but “the Good Life.” Rand again:

“In psychological terms, the issue of man's survival does not confront his consciousness as an issue of "life or death," but as an issue of "happiness or suffering." Happiness is the successful state of life, suffering is the signal of failure, of death...

Happiness is the successful state of life, pain is an agent of death. Happiness is that state of consciousness which proceeds from the achievement of one's values...

“But neither life nor happiness can be achieved by the pursuit of irrational whims. Just as man is free to attempt to survive in any random manner, but will perish unless he lives as his nature requires, so he is free to seek his happiness in any mindless fraud, but the torture of frustration is all he will find, unless he seeks the happiness proper to man. The purpose of morality is to teach you not to suffer and die, but to enjoy yourself and live.”

Such is the nature of a rational morality. The fact that the world is constituted as it is, means that if life is our standard -- my life, here on this earth -- then we ought to recognise the value of a rational morality, and if we wish to achieve happiness we ought to act upon values derived from a rational morality focused upon life on this earth.

What the hell else could ever be as important?

Let me say it again on conclusion: the standard for morality -- the rational standard -- is not obedience to what your God says or Moses says; it's not doing what your priest or your pastor or your Imam says; it's not subscribing to the same standards as your teachers or your peers the folks who live next door; it's not listening to what your own "inner voice" seems to say, or what your mother or your father or your Great Grandfather Stonebender used to say. Not if it defies reason.

The rational standard is Life, our life, and the lives of those we love. The immediate beneficiary of our actions is not others; it's ourself, and the purpose of such a standard is not to suffer and die, but to enjoy ourselves and live. (Once we've identified and internalised ethical guidelines to further our own flourishing, we can then only then safely listen to our own "stomach feeling," but it would be fatal to do so any earlier.)

TO TURN DESCARTES ON on his head (which is no less than the silly French philosopher deserves), the basic ethical principle is this:

"I am, therefore I'll think!"

Because if we don't think clearly there'll soon be no "I" around to think about.

I hope you think about that.

PS: For your homework, if you want to know more about Objectivist morality then you might want to act on that ...

- 'The Objectivist Ethics,' by Ayn Rand, in her book The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism.

- Audiobook excerpt from the introduction to The Virtue of Selfishness.

- Religion and Morality - a free talk by Onkar Ghate at the Ayn Rand Institute web page.

- Is-Ought? Not a Problem - Not PC

- Why Morality at All? - Not PC

- Does Evil Exist? - Not PC

- Cue Card Libertarianism: Morality - Not PC

Labels: Anarchy, Ethics, Religion

* * * *

Thursday, April 03, 2008

Cooperative Homesteads Housing, Minnesota - Frank Lloyd Wright (1942)

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned by a group of enthusiastic homesteaders to design a cooperative project for their shared property, on which they were each to pursue their personal and agricultural dreams.

The earth-bermed rammed earth houses Wright designed are unique in his and every other canon. Each house was to cost approx. $1400 in 1942 dollars. More here.

The enthusiastic homesteaders were eager to build them. Sadly however, the whole project was extinguished by World War II.

Labels: Architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright

* * * * *

Friday, March 27, 2009

Brainy billboards

Billboards don't have to be as boring as National's blancmange offerings last year, as some of these examples demonstrate.

Miele vacuum cleaners, on a billboard near a flight school:

Kill Bill. Crap film, inventive billboard:

Tide Detergent. After a few weeks the background becomes progressively dirtier . . .

A "bright idea" for The Economist magazine:

Bic razors, in Spain:

Extra strong sellotape, in Malaysia:

Paint ad on a building in Columbus, Ohio:

Many more of these here. [Hat tip Stephen Hicks]

* * * * *

Thanks for reading. Your reward is Anna Netrebko. She can sing a bit:

![coop_hmstd_02[3] coop_hmstd_02[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjEz-g3TTjzBJFBYw5hTHP690-P5e61GE8rl2w-sX2JfVxpd-y2c0kywp4BvNfsH9L1j8RENDcotL-7APrVhyphenhyphenDy73Sw3w69pkkPs5DtDJiSsfh4YV8iQbcZPkN651PXh08mowBp/?imgmax=800)

![coop_hmstd_04[3] coop_hmstd_04[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhsjDogYvBaUuTnVhUrVOH-za70QRkaINP3Pa3dPLuLmSksfY66j6LIZ4Fhr307gYiLgLYA8fiZXJ_CdpoB4B7v1rkm_nMWYMqaHuIPT1iR8-y9gd8iJhPlmgm0GUk5-xHt8UbG/?imgmax=800)

![coop_hmstd_01[6] coop_hmstd_01[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjqGf4DVT3nYMqbc1HlPYrtI7Yokl5yDmv2EEeEQj9L4HNvFsrT0RZ9SX8453P-6ONDz-psBt0E67X7596dGrHv4O0JShDg48_XQjM55fKWQXFQfQaAZjVF7YUGNC0zODtjXX_NUQ/?imgmax=800)

18 comments:

Anna Netrebko's voice is so beautiful. I am sure that Anna can do a duet with the the Tongan Diva, 'Elisapeti Wolfgramm because they have perfect voices. They can both hit the high notes without screaming.

I saw Anna Netrebko in the recent New York Met Opera HD cinema performance of Tales of Hoffman. She was brilliant and what a wonderful personality. There were some other great performers in that production, especially that by the young Kate Lindsey.

Julian

Peter,

Much as I appreciate the web traffic, you really should remove the link to my post until you've actually read my post. Nothing you have said in yours addresses my points - not even your quotation of scripture... I mean... something that appears to be an excerpt of a self-help book by Ayn Rand.

For your convenience, I've summed up what I was actually saying. If you can address the actual argument, I will be happy to have my mind changed or respond accordingly, but it is really frustrating to be linked to with a series of arguments and statements that have little or nothing to do with what I was saying.

And that post is...

Here is the link.

On free will vs determinism -

My arguments will be divided here into two parts, issues morality and

epistemology. Morality first -

"In the words of Ayn Rand, the determinist argument—that you’re neither to be blamed nor lauded for your behaviour—is simply “an alibi for weaklings.”"

I wouldn't call this a "determinist argument". Some Determinists may make this argument, I do not. In the past, the decision to assign blame has resulted in modifying human behaviour. Determinism changes the rationality behind assigning blame from being a moral imperative, to examining reality, and determining the chance of success or failure in achieving desirable results from taking such an action.

Epistemology -

One of the more intelligent things Rand said was "A is A" - a thing is a thing regardless of your feelings. A thing does not exist simply because you desire it, or because it provides a convenient justification for taking actions. As such, all issues of morality are irrelevant in proving the existence of free will.

Determinism, otherwise known as "causality", exists. No one is disputing this. "Free will" is an argument that states that human beings are capable of acting outside of normal causality. The statements you've provided do not show evidence of any decisions that could not be explained by a cause and effect relationship. What they DO prove however is that we are self aware. Self awareness, while being a very interesting phenomenon, does not prove that human decisions are not simply a link in a long chain of causality.

"We have consciousness. Consciousness is endowed by its nature with the faculty of free will"

Self awareness does not contradict deterministic behaviour, it simply adds another causal factor that influences outcomes. For instance I would not be writing about self awareness and concepts like free will if I wasn't self aware. Self awareness is self-evident, free will is not.

David S

So, according to you, determinism and causality are the same.

LGM

Determinism is the acknowledgement that causality explains human behaviour.

David S,

Causality is about physical existence and not about human. The universe started with no humans, but causality was there right from the beginning. I am sure that you know the difference? Physical reality is deterministic whether there are humans in this universe or not and that's a fact.

"Causality is about physical existence and not about human."

ridiculous.

"Physical reality is deterministic whether there are humans in this universe or not and that's a fact."

Well, yes, of course, when did I say otherwise?

David S

That's not what you wrote in your earlier post. You wrote that determinism was otherwise known as causality. In other words the two terms referred to the same concept.

If you are going to venture forth into this debate you sure as heck better tighten up your use of terminology, concepts, principles and premise. The reason you should is that so doing avoids the sloppy thought and careless sleight of hand that often allows invalid argument to go undetected.

By the way, are you aware of what the term "stolen concept" relates to.

LGM

They are the same concept, from a certain point of view. Determinism describes an absence of concepts (like free will). It's a bit like the term 'Atheism'. Atheism not a doctrine, it refers to the absence of theology.

David S, you said that Determinism describes an absence of concepts (like free will), but inanimate objects don't form concepts, do they? It is only a rational being that have the ability to form concepts, thus it only makes sense to talk determinism when there is a human is involved.

A hydrogen atom doesn't have any concept about quantized photon energy. The Hydrogen atom just acted according to its nature (identity) when it absorbed a photon with the right excitation-energy while deflecting or scattering others that are outside these photon quantized excitation energy levels. This process is deterministic, but when a human studies this process, then determinism and indeterminism must be used to describe the process, since humans have limitation in their senses. It is us humans that use these terms.

Do you see what I mean?

David S

Wriggle. Wriggle. Rationalise. Wriggle. Slide. Squirm. Wriggle.

They are different concepts. Do not be attempting to engage in the deception of substituting one for the other. That would be dishonest.

By the way, do you know what the term "stolen concept" relates to.

Just interested.

LGM

"but inanimate objects don't form concepts, do they?"

No, they don't, but the words we use to describe the world around us are all concepts. Aristotle pointed out that you don't truly understand something until you understand it 'down to the root'. Do you understand a hydrogen atom 'down to the root'?. You don't of course, physics hasn't gotten that far, indeed it may never get that far. The image we have of how the universe works right now is an educated guess. We have used a combination of reason and empirical observation to create a logical construct, a 'useful fiction' as Kant would say. This is what science does.

The list of things we know absolutely is actually very short. We are aware, and we exist. Awareness is self evident, and thus our existence is also self evident. Accepting all other information as "fact" requires some degree of faith.

LGM, no I was not aware of what, "the stolen concept" was, I had to go googling. After doing a little reading, I stand by my statement that it depends on your point of view.

Objects behave deterministically. Humans behave deterministically. Objects behave according to causality. Humans behave according to causality. A key point to the discussion is that these concepts are interchangeable.

This is why I don't get into all this determinism stuff. You get bogged down in exceptions to rules for no good reason.

How about 'Elisapeti Wolfgramm's younger sister's voice (Natalia), which I think is up there with the likes of Anna Netrebko's. Here is her singing ave maria on youtube.

Ave Maria

She is a rock/pop singer herself and a bass guitar player, but that doesn't mean she can't sing opera, definitely her voice is up right there with the opera professionals.

David S

The two concepts are not the same.

I'm glad you looked up the stolen concept. It's important. Apply it to determinism and you'll see why.

LGM

Post a Comment