Planet ZIRP was supposed to be an emergency stopover not a

permanent settlement. Time for the US Federal Reserve to make a move.*

But can it, asks Gerald O’Driscoll in this guest post?

But can it, asks Gerald O’Driscoll in this guest post?

The US Federal Reserve is set to act this week to raise short-term interest rates. There are a number of technical and policy questions raised by this long-anticipated decision. The Fed conventionally raises short-term interest rates by selling short-term Treasury obligations. It no longer owns any short-term Treasuries to sell.

Based on prior statements, the Fed is expected to increase the interest rate on reserves held by commercial banks at Federal Reserve banks. The Fed is operating in uncharted waters. It is not clear how increasing interest on reserves will affect other short-term interest rates. Further, the Fed is already paying commercial banks over $6 billion in interest payments annually. That amounts to a fiscal transfer from taxpayers to bankers. Raising rates will only increase that transfer. As we approach a presidential election year, that is likely to become grist for political mills.

The Fed could also raise the interest rate on reverse repurchase agreements at a facility at the New York Fed. The Fed is effectively borrowing money from financial institutions like money market funds. It functions as a subsidy to those institutions, as the Federal Reserve System has no business or policy reason for borrowing money. Once again, I would anticipate political questioning of such a move.

Free-market economists are in a policy conundrum. Most have long advocated higher interest rates.

But the facilities through which that policy will now be effected have questionable validity. Some of the same economists advocating higher short-term rates have also been critical of the Fed’s payment of interest on reserves. Those economists must now ask for more of something they wanted none of. Operational considerations are confounding substantive policy.

All of the above is a consequence of the Fed’s having implemented extraordinary monetary policy. That included shedding all liquid, short-term Treasury obligations in favour of loading up on risky and illiquid, long-term debt obligations. Critics argued the Fed would rue the day it did that. Now that day has arrived.

Gerald O’Driscoll is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, and a widely

quoted expert on international monetary and financial issues. Previously the

director of the Center for International Trade and Economics at the Heritage

Foundation, O’Driscoll was senior editor of the annual Index of Economic

Freedom, co-published by Heritage and The Wall Street Journal. He has

also served as vice president and director of policy analysis at Citigroup.

Before that, he was vice president and economic advisor at the Federal Reserve

Bank of Dallas. He also served as staff director of the Congessionally mandated

Meltzer Commission on international financial institutions. O’Driscoll has

taught at UCSB, Iowa State University and New York University. He is widely

published in leading publications, including The Wall Street Journal.

He appears frequently on national radio and television, including Fox Business

News, CNBC and Bloomberg. He is a member of the Mont Pelerin Society, and is a

director of the Association of Private Enterprise Education. O’Driscoll holds a

B.A. in economics from Fordham University, and an M.A. and Ph.D in economics

from UCLA.

Gerald O’Driscoll is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, and a widely

quoted expert on international monetary and financial issues. Previously the

director of the Center for International Trade and Economics at the Heritage

Foundation, O’Driscoll was senior editor of the annual Index of Economic

Freedom, co-published by Heritage and The Wall Street Journal. He has

also served as vice president and director of policy analysis at Citigroup.

Before that, he was vice president and economic advisor at the Federal Reserve

Bank of Dallas. He also served as staff director of the Congessionally mandated

Meltzer Commission on international financial institutions. O’Driscoll has

taught at UCSB, Iowa State University and New York University. He is widely

published in leading publications, including The Wall Street Journal.

He appears frequently on national radio and television, including Fox Business

News, CNBC and Bloomberg. He is a member of the Mont Pelerin Society, and is a

director of the Association of Private Enterprise Education. O’Driscoll holds a

B.A. in economics from Fordham University, and an M.A. and Ph.D in economics

from UCLA.This guest post previously appeared at the Alt-M blog.

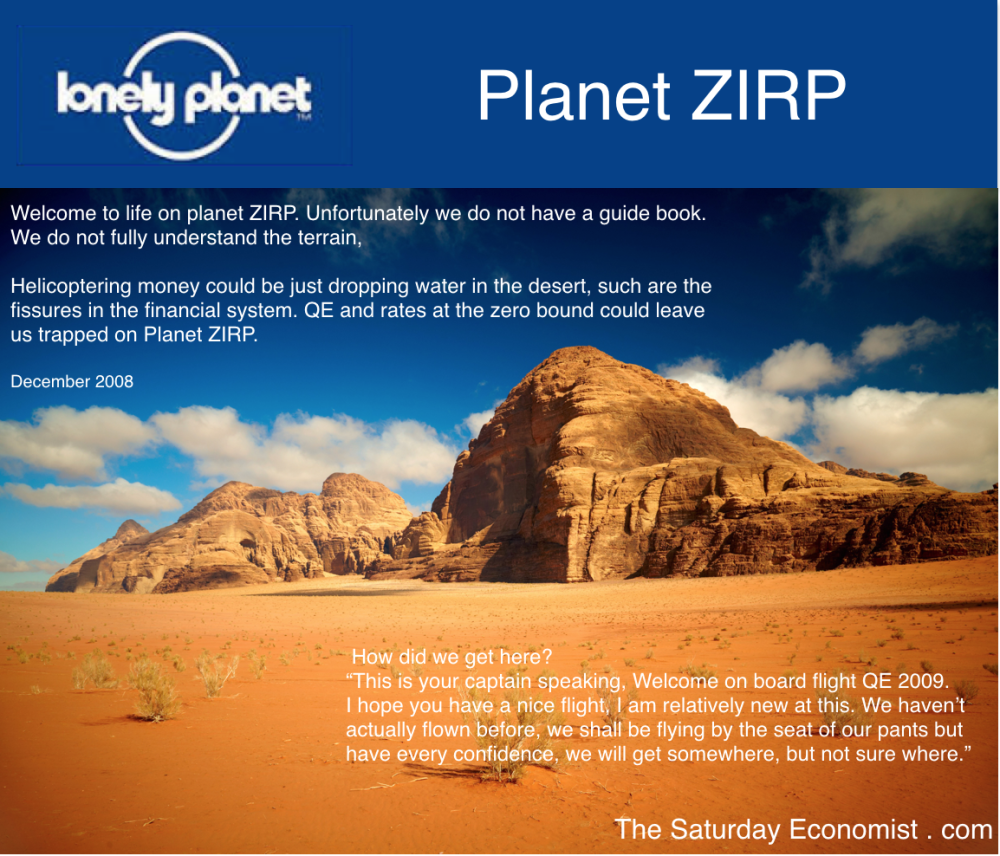

* ZIRP = Zero Interest Rate Policy. Quip (and picture) by the Saturday Economist.

No comments:

Post a Comment