Allow to me to pull on your coat about something: a wee story about Art, Tragedy and Catharsis.

You’re watching a good ‘weepy’ with a box of tissues on hand, and you cry your eyes out – that’s what we call ‘catharsis,’ isn’t it?

As everyone knows (or thinks they know) catharsis is a healthy purging of all your repressed emotions. You see a devastatingly good film or heroically moving play and pretty soon there ain't a dry eye in the house.

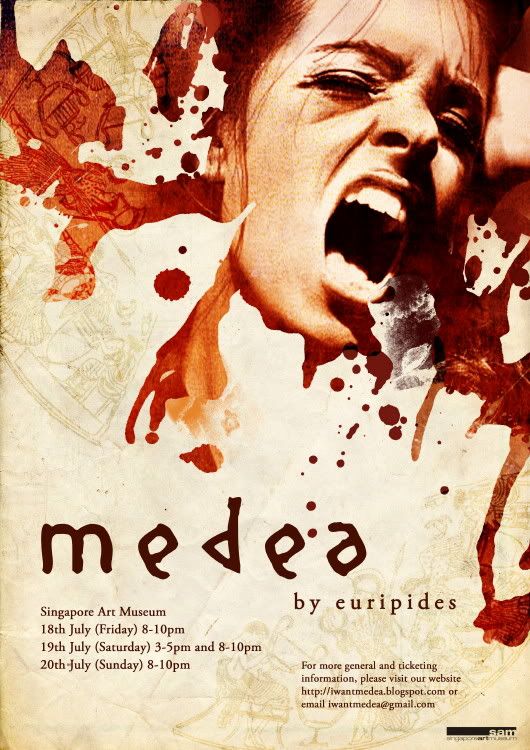

Aristotle himself suggested that’s what happens when you see decent drama – particularly a good tragedy like Medea or Oedipus Rex where the stage ends up littered with corpses, and the hero ends up … well … we all know where Oedipus ended up and what what happened to Medea’s children, don’t we. Who wouldn’t weeping over all that?

Aristotle himself suggested that’s what happens when you see decent drama – particularly a good tragedy like Medea or Oedipus Rex where the stage ends up littered with corpses, and the hero ends up … well … we all know where Oedipus ended up and what what happened to Medea’s children, don’t we. Who wouldn’t weeping over all that?

So, we all know about catharsis. Or think we know. And in case you don’t know, we got the whole notion from Aristotle who argued in his Poetics that catharsis is, in fact, the number one reason for good drama and good literature.

That’s quite a claim: that the number one reason for good drama and good literature is is a healthy purging of all your repressed emotions

Ayn Rand didn’t agree. She said the number one reason for literature, and indeed for all art, is that it anchors us to existence. Art we respond to, she argued, shows us in concrete form what our own individual world-view actually is.

We experience a performance of Tosca, for example, or we look at a statue of David or a painting of Icarus Landing, and we say to ourselves (if we’re healthy): “This is the way I see things. This is the way I feel about the world.” In short, when art truly touches us we say to ourselves: “This is me!” And it is.

This is why art is so crucially – selfishly - important for us. Because the human mind operates on the conceptual level, we need art to help us integrate our broadest abstractions, and to bring them before us in concrete form. You need art to concretise for you -- in a painting, a story, a piece of music -- the way that you view the world around you and how you feel you fit in. Everybody sees the world differently, some aspects being more or less important than others. The artist selects elements of reality to re-create and integrate into his work based on his own most profound choice of how he sees the world – and if we see it the same way we experience almost a shock of recognition.

So art, according to Ayn Rand, is a re-creation of reality. A selective re-creation of reality. The elements in each art-work are selected according to the artist’s view of what he sees as fundamental – as being of real metaphysical importance. “By a selective re-creation, art isolates and integrates those aspects of reality which represent man’s fundamental view of himself and of existence.” That’s why we experience such a profound shock when we ‘recognise’ the artist’s selection as our own. That’s why art art we respond to we respond to so powerfully, and why it feels so personally important.

So we have two views of art that appear to be in fundamental disagreement. So it seems.

But … what if we got Aristotle wrong?

What if Aristotle didn’t actually say what everyone thought he said? What if Aristotle didn’t agree either that the the purpose of art and drama is simple sharing a protagonist’s emotions.

Well, arguably he didn’t. Arguably, our whole idea of catharsis and what Aristotle is supposed to have said about it is based on a profound mistranslation. Leon Golden, Professor of Classics at Florida State University and described as “the single most influential living authority on Aristotle's Poetics” argues that on this subject we’ve all got Aristotle wrong, and since 1962 he’s written a book and several articles arguing the case. The Greek word katharsis, he argues, has been mistranslated leading to our misunderstanding of what Aristotle was actually saying.

Based on some elegant philological detective work, Golden suggests that tragic katharsisis as Aristotle meant it is neither medical purgation, nor intellectual purification; katharsis, he says, is "intellectual clarification":

Katharsis is that moment of insight which arises out of the audience’s climactic intellectual, emotional, and spiritual enlightenment, which for Aristotle is both the essential pleasure and essential goal of mimetic art.

A moment of insight arising out of your climactic intellectual, emotional, and spiritual enlightenment. That’s a serious engagement with something!

So what does Aristotle mean by ‘mimetic art’? He means art that re-creates reality. Uh huh! You see where I’m going with this? As Leon Golden has it, mimesis comes from a fundamental "desire to know." People derive a pleasure of "learning and inference" from mimesis; a katharsis far different to one commonly understood by the word. This is what art that does re-create reality casts such a powerful intellectual, emotional, and spiritual spell upon us.

This is a view that must surely resonate with Objectivist aestheticians. Golden concludes his argument:

For Aristotle art is neither psychological therapy for the mentally ill nor a sermon directed at imposing an appropriate ethical and moral discipline on an audience. On the contrary, his aesthetic theory explains our attraction to tragedy and comedy on the basis of a deeply felt impulse, arising from our very nature as human beings, to achieve intellectual insight through that process of learning and inference which represents the essential pleasure and purpose of artistic mimesis.

It seems once again that the position of Ayn Rand and her teacher were once again not very far from each other. When Rand talks of art 'recreating reality' we can see her standing once again on Aristotle’s shoulders - one giant standing upon the shoulders of another.

One final word: none of this means you that you aren’t allowed to cry at the movies if you want to. If that’s your bag, then I wish you good weeping.

This post is based on my 2004 post at SOLO, archived here. But this one is way better.

No comments:

Post a Comment