Site plan of ‘Usonia,’ Pleasantville, New York, 1947

“The home is a shelter, not a fortress.” That was the ethos behind the post-war Usonian community built amidst a heavily wooded site in Pleasantville, upstate New York, guided by the masterplan of architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Shelters don’t need fences, only screens. Each home in this 50-strong subdivision had its own circular lot, shown above, the site’s natural ‘screens’ being the existing trees and landscape existing in the interstices in between the circular lots, which were shared and covenanted to the community.

This makes a very different place to live in than your traditional cut-felled-filled-and-fenced subdivision.

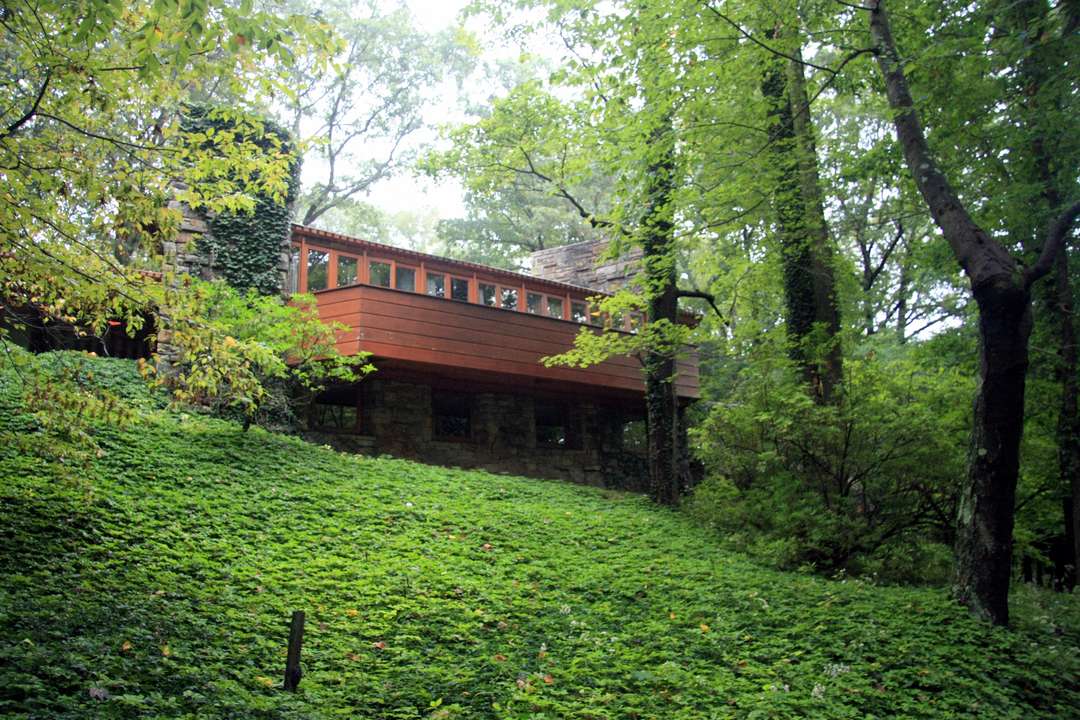

Reisley House, Image via Flickr

Reisley House, Image via Flickr

This simple arrangement enabled owners to enjoy the very thing that drew them to the site in the first place: the landscape itself, and the chance to live with it.

And the relaxed relationship with landscape and neighbours that was encouraged to develop became the community’s cement:

Usonia was initially established in 1947, and the project's original families have played a remarkably consistent role in the ongoing development of the community, with only 12 of the 50 houses changing hands during the first 40 years — six of those to younger family members. Its residents have reported an unusual degree of connectedness amongst neighbours, with doors left unlocked, children roaming from house to house, and former residents keeping in touch almost 70 years after their initial meeting.

Lerner House. Image via Flickr

Some of the main lessons to be learned from Usonia and Wright’s masterplan are summarised in this article at Architizer. Taking that article’s lead, I would characterise the lessons slightly differently however, among them being:

- Shared landscapes can work

Private lots living within a shared covenanted natural landscapes – with perhaps a body corporate structure for maintenance, pruning, planting and the like – gives protected, private spaces that can open benevolently to the beauty around them; - Keep roads narrow and winding

”Usonia’s intentionally narrow roads privilege the human over the automobile, forcing cars to drive at slower speeds, and encouraging residents to walk through the woods to get to neighbours' homes. Smaller roads also leave a lot more room for the scenery, leaving more flora for absorbing water runoff, and making even a quick spin into a scenic drive.” - Diminish boundaries

Square sections surrounded by fences create easily seen boundaries, and dead spaces in each section that neither neighbour enjoys. Wright designed lots as a series of circles within the greater landscape, blurring boundaries and making the effective visual boundaries of each lot almost as far as each eye could see, allowing lots to mould fluidly to the contours, and opening up what would normally be dead space at corners to become (quite literally) live space. - Landscape is at least half the project

Owners move to a site like this to enjoy the landscape, so designing with it seems more than common sense. “Wright is, of course, renowned for his efforts at joining interior and exterior, bringing the landscape into the building. Usonia was no different, in that topography played a big role in the design. In his design of the Reisley House, for instance, Wright insisted that it be built on the side of the hill, rather than on top, so that its residents would experience the full benefit of living on a hill. Similarly, the narrow roads wind around the contours, while every house is designed with the view of the landscape as a primary concern.” - Keep doors unlocked

”Once you get to know your neighbours, keep your doors unlocked. A posture of openness toward your surroundings increases the quality of life. The home is a shelter, not a fortress.”

And finally,

- Enlist an architect with vision

One how can design your house to be in and of the site, instead of on top of it.

Perhaps it’s this last that’s truly missing at that site everyone’s talking about in Titirangi…

Friedman House. Image via Flickr

[Hat tip for images to Architizer]

5 comments:

"One of America’s most successful, if little-known, planned communities was designed by America’s best-known architect. The project anticipated the need for sustainable development, for a community in tune with its landscape and with nature, whose individually crafted houses all carry vast aesthetic interest while remaining affordable for young middle-class families."

Surely not a utopian idea! Instead what we have is a flattened landscape, and houses which all look the same and are always painted the colour of mud. Diversity is lauded in other areas of life, why not in housing? Looking at the subdivisions around South East Auckland, you wouldn't want to have too many alcoholic beverages or else you won't be able to distinguish your house on a dark night.

@Ruth: Couldn't agree more. It's not utopian: it should be common sense. Instead...

It works in limited cases because only a relative few can share space and the vision. There have been plenty of lifestyle experiments over the years (Quadrant did an article on some Australian ones a while ago) but people clash. I think this example looks wonderful but its expanse and relative low density make it expensive in modern cities where density is becoming important.

I live on an acre in the subhurbs and bought it because it was private. The far from expensive house dates from 1940 but was designed / built by an American. While I've modified it to better use the sun and leafy outdoors the basic layout remains as built. It is the opposite of the basic NZ house models of that time really - built at the back of the sloping section, north facing for sun with lots of north facing glazing, an openish plan and still modern layout. Common sense to an American maybe.

Ruth & PC - What Wright did was beautiful, but I'm afraid it's only common sense if you have very low density and have very deep pockets.

Well, the context here of course is a natural landscape already in existence, with few regulations imposing constraints on development. But I'm pretty certain even in the context of south-east Auckland or north Canterbury subdivisions, say, that the circular-lot supposition can be used to generate greater privacy and greater new landscape than do the present cut-fill-and-fence arrangements.

In fact, I'm working on ideas for both contexts as we speak...

Post a Comment