Guest post by Dan Steinhart, introducing John Mauldin

Humans tend to believe what they're told by authority figures. Even in the face of contradictory evidence.

The Milgram Experiment taught us this in 1963. Posing as scientists, researchers instructed volunteers to inflict painful electric shocks on what they thought were other innocent volunteers, as a penalty for answering questions incorrectly. The shockers couldn't see the people they were shocking, but could hear their reactions: terrible cries of pain, pounding on the wall, pleas to stop, and eventually, ominous silence.

The Milgram Experiment taught us this in 1963. Posing as scientists, researchers instructed volunteers to inflict painful electric shocks on what they thought were other innocent volunteers, as a penalty for answering questions incorrectly. The shockers couldn't see the people they were shocking, but could hear their reactions: terrible cries of pain, pounding on the wall, pleas to stop, and eventually, ominous silence.

Of course, it was all a ruse, but the shockers didn't know that. They thought they were effectively torturing the victims. Yet most shockers ignored the victims' agonized pleas to stop, opting instead to obey the "scientist's" commands to continue.

Why? Because the "scientist" was an expert. He was wearing a white lab coat, so he must know best.

We treat economists similarly today, deferring to their expertise in economic matters, even when common sense suggests they are wrong. Paul Krugman says an alien invasion would cure our economic ills by forcing us to spend money to defend against their attack. If a stranger on the bus said that, you might direct him to the nearest mental facility.

We treat economists similarly today, deferring to their expertise in economic matters, even when common sense suggests they are wrong. Paul Krugman says an alien invasion would cure our economic ills by forcing us to spend money to defend against their attack. If a stranger on the bus said that, you might direct him to the nearest mental facility.

But Krugman? He has a framed MIT doctorate gracing his office wall, so he must know what he's talking about.

Here's a dirty little secret: Economists—particularly government and other mainstream ones—stink at their jobs. They're awful at forecasting the future. History shows that not only are economists incapable of forecasting recessions, they usually can't even recognize that we're in a recession once it's already started. If you were as bad at your job as the average economist is at his, you wouldn't have a job. Management would fire you, assuming they could do so before your horrendous decisions brought down the entire company.

With that background, I'm excited to share with you an excerpt from John Mauldin's fantastic new book, Code Red. As you might've guessed, the premise of the passage you'll read below is that mainstream economists have a horrific track record, a claim the book backs up with impressive stats. For investors, relying on mainstream economists' forecasts is a sure path to subpar returns.

But Code Red is about so much more. I plowed through it this over the weekend, and if I had to describe it in one word, it would be "satisfying." John Mauldin and his co-author Jonathan Tepper beautifully explain how seemingly unrelated pieces of the global economy fit together, how we've arrived at our near zero-interest rate world, and which countries are closest to crisis. What seems absurdly complex before reading the book becomes crystal clear afterward.

Here are a couple of the chapter titles, to give you an idea of the topics Code Red covers:

- 20th Century Currency Wars—The Barbarous Relic and Bretton Woods

- A World of Financial Repression

- Easy Money Will Lead to Bubbles, and How to Profit From Them

- How to Protect Yourself Against Inflation

- A Look at Commodities, Gold, and Other Real Assets

With that, I'll leave you to explore the excerpt for yourself. If you like what you read, you can purchase a copy of Code Red for 28% off the regular price by clicking here.

Enjoy.

Dan Steinhart

Managing Editor of The Casey Report

An Excerpt from Code Red:

Chapter 6 - Economists Are Clueless

By John Mauldin & Jonathan Tepper

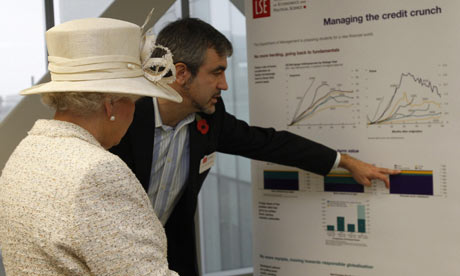

In November of 2008, as stock markets crashed around the world, the Queen of England visited the London School of Economics to open the New Academic Building. While she was there, she listened in on academic lectures. The Queen, who studiously avoids controversy and almost never lets people know what she's thinking, finally asked a simple question about the financial crisis, "How come nobody could foresee it?" No one could answer her.

In November of 2008, as stock markets crashed around the world, the Queen of England visited the London School of Economics to open the New Academic Building. While she was there, she listened in on academic lectures. The Queen, who studiously avoids controversy and almost never lets people know what she's thinking, finally asked a simple question about the financial crisis, "How come nobody could foresee it?" No one could answer her.

If you suspected that mainstream economists are useless at the job of seeing a crisis in advance, you would be right. Dozens of studies show that economists are completely incapable of forecasting recessions. But forget forecasting. What's worse is that they fail miserably even at understanding where the economy is today. In one of the broadest studies of whether economists could predict recessions and financial crises, Prakash Loungani of the International Monetary Fund wrote very starkly, "The record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished." This was true not only for official organizations like the IMF, the World Bank, or government agencies but for private forecasters as well. They're all terrible. Loungani concluded that the "inability to predict recessions is a ubiquitous feature of growth forecasts." Most economists were not even able to recognize recessions once they had already started.

In plain English, economists don't have a clue about the future.

If you think the Fed or government agencies know what is going on with the economy, you're mistaken. Government economists are about as useful as a fork in a sugar bowl. Their mistakes and failures are so spectacular you couldn't make them up if you tried. Yet now, in a Code Red world, we trust the same bankers to know where the economy is, where it is going, and how to manage monetary policy.

If you think the Fed or government agencies know what is going on with the economy, you're mistaken. Government economists are about as useful as a fork in a sugar bowl. Their mistakes and failures are so spectacular you couldn't make them up if you tried. Yet now, in a Code Red world, we trust the same bankers to know where the economy is, where it is going, and how to manage monetary policy.

Central banks say that they will know when the time is right to end Code Red policies and when to shrink the bloated monetary base. But how will they know, given their record at forecasting? The Federal Reserve not only failed to predict the recessions of 1990, 2001, and 2007, it didn't even recognize them after they had already begun. Financial crises frequently happen because central banks cut interest rates too late and hike rates too soon.

Trusting central bankers now is a big bet that (1) they'll know what to do and (2) they'll know the right time to do it. Sadly, they generally don't have a clue about what is going on.

Unfortunately, the problem is not that economists are simply mediocre at what they do. The problem is that they're really, really bad. And they're so bad that their ineptitude cannot even be a matter of chance. As the statistician Nate Silver pointed out in his book The Signal and the Noise:

Indeed, economists have for a long time been much too confident in their ability to predict the direction of the economy. If economists' forecasts were as accurate as they claimed, we'd expect the actual value for GDP to fall within their prediction interval nine times out of ten, or all but about twice in eighteen years.

In fact, the actual value for GDP fell outside the economists' prediction interval six times in eighteen years, or fully one-third of the time. Another study, which ran these numbers back to the beginning of the Survey of Professional Forecasters in 1968, found even worse results: the actual figure for GDP fell outside the prediction interval almost half the time. There is almost no chance that economists have simply been unlucky; they fundamentally overstate the reliability of their predictions.

So it gets worse. Economists are not only generally wrong, they're extremely confident in their bad forecasts.

If economists were merely wrong at betting on horse races, their failure would be harmlessly amusing. But central bankers have the power to create money, change interest rates, and affect our lives in every way—and they don't have a clue.

Despite their cluelessness, there's no overestimating the hubris of central bankers. On 60 Minutes in December 2010, Scott Pelley interviewed Chairman Ben Bernanke and asked him whether he would be able to do the right thing at the right time. The exchange was startling:

Pelley: Can you act quickly enough to prevent inflation from getting out of control?

Bernanke: We could raise interest rates in 15 minutes if we have to. So, there really is no problem with raising rates, tightening monetary policy, slowing the economy, reducing inflation, at the appropriate time. Now, that time is not now.

Pelley: You have what degree of confidence in your ability to control this?

Bernanke: One hundred percent.

There you have it. Bernanke was not 95% confident, he was not 99% confident—no, he had zero doubts about his ability to know what is going on in the economy and what to do about it. We would love to have that kind of certainty about anything in life.

We're not picking just on Bernanke; we're picking on all central bankers who think they're infallible. The Bank of England has had by far the largest QE program relative to the size of its economy (though the Bank of Japan is about to show it a thing or two). It has also had the worst forecasting track record of any bank, and the worst record on inflation. Sir Mervyn King, the head of the Bank of England, was asked if it would be difficult to withdraw QE. He very confidently replied,

I have absolutely no doubt that when the time comes for us to reduce the size of our balance sheet that we'll find that a whole lot easier than we did when expanding it…

(Are central bankers just naturally more arrogant than regular human beings, or are they smoking some powerful stuff at their meetings?)

Let's see whether this sort of absolute certainty is at all warranted.

In his book Future Babble, Dan Gardner wrote that economists are treated with the reverence the ancient Greeks accorded the Oracle of Delphi. But unlike the vague pronouncements from Delphi, economists' predictions can be checked against the future, and as Gardner says,

Anyone who does that will quickly conclude that economists make lousy soothsayers.

(As an aside, we suspect that economists may be the modern-day functional equivalent of tribal shamans. Instead of peering at the intestines of sheep to forecast the future, we look at data through the lenses of models we create, built with all our inherent biases, and then confidently predict the future or try to guide government policy in one direction or another, generally along paths that fit the favor depending on whether we are telling our fellow tribe members and leaders and potential leaders what they want to hear. It may be that economics is more like religion and less like science than most of us want to admit.)

The nearsightedness of economists is nothing new. In 1994 Paul Ormerod wrote a book called The Death of Economics. He pointed to economists' failure to forecast the Japanese recession after their bubble burst in 1989 or to foresee the collapse of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. Ormerod was scathing in his assessment of economists:

The ability of orthodox economics to understand the workings of the economy at the overall level is manifestly weak (some would say it was entirely non-existent).

When people think of economic forecasts, they almost always think of recessions, while economists think of forecasting growth rates or interest rates. But the average person in the street only wants to know, "Will we be in a recession soon?"—and if the economy is already in a recession, he or she wants to know, "When will it end?" The reason most working Americans care is that they know recessions mean job cuts and firings.

Figure 6.1 Recessions lead to falls in GDP and spikes in the unemployment rate  Source: Variant Perception, Bloomberg

Source: Variant Perception, Bloomberg

Unfortunately, economists are of no use to the man or woman in the street. If you look at the history of the last three recessions in the United States, you will see that the inability of economists and central bankers to understand the state of the economy was so bad that you might be tempted to say they couldn't find their derrieres with both hands.

Figure 6.2 Economists have never predicted a recession correctly

Source: Societe Generale Equity Research

Let's remind ourselves what a recession is and how economists decide that one has started. A recession is a downturn in economic activity. Normally, a recession means unemployment goes up, GDP contracts, stock prices fall, and the economy weakens. The lofty body that decides when a recession has started or ended is the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research. It is packed with eminent economists and other extremely smart people. Unfortunately, their pronouncements are completely unusable in real time. Their dating of recessions is authoritative and more or less accurate, but this exercise in hindsight comes together long after a recession has started or ended.

To give you an idea just how late recessions are officially called, let's look at the past three. The NBER dated the 1990-91 recession as beginning in August 1990 and ending in March 1991. It announced these facts in April 1991, by which time the recession was already over and the economy was growing again. The NBER was no faster catching up with the recession that followed the dotcom bust. It wasn't until June 2003 that the NBER pinpointed the 2001 recession—a full 28 months after the recession ended. The NBER didn't date the recession that started in December 2007 until exactly one year later. By that time, Lehman had gone bust, and the world was engulfed in the biggest financial cataclysm since the Great Depression.

The Federal Reserve and private economists also missed the onset of the last three recessions—even after they had started. Let's look quickly at each one.

Starting with the 1990-91 recession, let's see what the head of the Federal Reserve—the man who is charged with running American monetary policy—was saying at the time. That recession started in August 1990, but one month before it began Alan Greenspan said, "In the very near term there's little evidence that I can see to suggest the economy is tilting over [into recession]." The following month—the month the recession actually started—he continued on the same theme: "... those who argue that we are already in a recession I think are reasonably certain to be wrong." He was just as clueless two months later in October 1990, when he persisted, "... the economy has not yet slipped into recession." It was only near the end of the recession that Greenspan came around to accepting and acknowledging that it had begun.

The Federal Reserve did no better in the dotcom bust. Let's look at the facts. The recession started in March 2001. The tech heavy NASDAQ Index had already fallen 50% in a full-scale bust. Even so, Chairman Greenspan declared before the Economic Club of New York on May 24, 2001,

Moreover, with all our concerns about the next several quarters, there is still, in my judgment, ample evidence that we are experiencing only a pause in the investment in a broad set of innovations that has elevated the underlying growth rate in productivity to a level significantly above that of the two decades preceding 1995.

Charles Morris, a retired banker and financial writer, looked at a decade's worth of forecasts by the geniuses at the White House's Council of Economic Advisors. In 2000, the council raised their growth estimates just in time for the dot-com bust and the recession of 2001-02. In a survey conducted in March 2001, 95% of American economists said there would not be a recession. The recession had already started that March, and the signs of contraction were evident. Industrial production had already been contracting for five months.

You would have thought that their failure to forecast two recessions in a row might have sharpened the wits of the Federal Reserve, the Council of Economic Advisers, and private economists. Maybe they would have tried to improve their methods or figured out why they had failed so miserably. You would be wrong. Because along came the Great Recession, and—once again—they completely missed the boat.

Let's look at what the Fed was doing as the world was about to go up in flames in 2008. Recently, complete minutes of the Fed's October 2007 meeting were released. Keep in mind that the recession started two months later, in December 2007. The minutes make for depressing reading. The word recession does not appear once in the entire transcript.

It gets worse. The month the recession started, the Federal Reserve was all optimistic laughter. Dr. David Stockton, the Federal Reserve chief economist, presented his view to Chairman Bernanke and the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee on December 11, 2007.

When you read the following quote and choke on your breakfast or lunch, remember that at the time the Fed was already providing ample liquidity to the shadow banking system after dozens of subprime lenders had gone bust in the spring, the British bank Northern Rock had been nationalised and spooked the European banking system, dozens of money market funds had been shut due to toxic assets, credit spreads were widening, stock prices had started to fall, and almost all the classic signs of a recession were evident. These included an inverted yield curve, which had received the casual attention of New York Fed economists even as it screamed recession.

Read these words of the Fed's chief economist and weep. You can't make this stuff up.

Overall, our forecast could admittedly be read as still painting a pretty benign picture: Despite all the financial turmoil, the economy avoids recession and, even with steeply higher prices for food and energy and a lower exchange value of the dollar, we achieve some modest edging-off of inflation. So I tried not to take it personally when I received a notice the other day that the Board had approved more frequent drug-testing for certain members of the senior staff, myself included. [Laughter] I can assure you, however, that the staff is not going to fall back on the increasingly popular celebrity excuse that we were under the influence of mind-altering chemicals and thus should not be held responsible for this forecast. No, we came up with this projection unimpaired and on nothing stronger than many late nights of diet Pepsi and vending-machine Twinkies.

We do not want to pick on Dr. Stockton unnecessarily, as all other government economists were equally awful. The President's Council of Economic Advisers' 2008 forecast saw positive growth for the first half of the year and foresaw a strong recovery in the second half.

Unfortunately, private-sector economists didn't do much better. With very few exceptions, they failed to foresee the financial and economic meltdown of 2008. Economists polled in the Survey of Professional Forecasters also failed to see a recession developing. They forecasted a slightly below-average rate of 2.4 percent for 2008, and they thought there was almost no chance of a recession as severe as the one that actually unfolded. In December 2007, a Businessweek survey showed that every single one of 54 economists predicted the U.S. economy would avoid a recession in 2008. The experts were unanimous that unemployment wouldn't be a problem, leading to the consensus conclusion that 2008 would be a good year.

As Nate Silver has pointed out, the worst thing about the bad predictions isn't that they were awful; it's that the economists in question were so confident in them:

This was a very bad forecast: GDP actually shrank by 3.3% once the financial crisis hit. What may be worse is that the economists were extremely confident in their bad prediction. They assigned only a 3% chance to the economy's shrinking by any margin over the whole of 2008. And they gave it only about a 1-in-500 chance of shrinking by 2 percent, as it did.

It is one thing to be wrong. It is quite another to be consistently and confidently and egregiously wrong.

As the global financial meltdown unfolded, Chairman Bernanke, too, continued to believe that the United States would avoid a recession. Mind you, the recession had started in December 2007, yet in January 2008 Bernanke told the press, "The Federal Reserve is not currently forecasting a recession." Even after banks like Bear Stearns needed to be rescued, Bernanke continued seeing rainbows and candy-coloured elves ahead for the U.S. economy. He declared on June 9, 2008, "The risk that the economy has entered a substantial downturn appears to have diminished over the past month or so." At that stage, the economy had already been in a recession for the past six months!

Why do people listen to economists anymore? Scott Armstrong, an expert on forecasting at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, has developed a "seer-sucker" theory: "No matter how much evidence exists that seers do not exist, suckers will pay for the existence of seers." Even if experts fail repeatedly in their predictions, most people prefer to have seers, prophets, and gurus with titles after their names tell them something—anything at all—about the future.

Why do people listen to economists anymore? Scott Armstrong, an expert on forecasting at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, has developed a "seer-sucker" theory: "No matter how much evidence exists that seers do not exist, suckers will pay for the existence of seers." Even if experts fail repeatedly in their predictions, most people prefer to have seers, prophets, and gurus with titles after their names tell them something—anything at all—about the future.

So, we have catalogued the incredible failures of economists to predict the future or even to understand the present. Now, with their record in mind, think of the vast powers Fed economists have to print money and move interest rates. When you contemplate the consummate skill that would actually be required to manage Code Red policies, you realize they're really just flying blind. If that doesn't scare the living daylights out of you, you haven't understood this chapter so far.

His website is MauldinEconomics.Com.

Dan Steinhart (right) is a CPA and Big 4 accounting firm alumni, reformed Wall Street trader, and the Managing Editor of The Casey Report .

This post first appeared in the Casey Daily Dispatch.

2 comments:

"The Milgram Experiment" is that what it was called!

Damn! Would you believe I was subjected to that experiment as a primary school kid age 9. Fucking sadists. They showed me this box with a steel and and boxing glove. They showed what a mechanical punch looked like at a low force which looked pretty violent.

I never forget, I was placed in the stationary storage room at a table with 10 buttons. 1 was a soft punch 10 was all out. Every time the light went on showing the "other" person made a mistake I had to push a button. It was horrible but rather then refuse and walk away, I stayed put and did was I was told by adults. I do recall picking button 1 all the time. Disgusting thing to do to a kid.

An interesting thing that people don't know about Milgram's experiment is that follow up interviews and attempts to replicate it revealed the vast majority of participant recognized it was faked but play along - similarly to what happens when people are hypnotized.

It seems to say something still relevant but more complex about peoples desire to be cooperative than first blush reveals.

Some attempts to dig into it - with tests that really did hurt people - revealed subjects have a much stronger aversion to causing pain than Milgram's set up showed when they recognize the real harm.

Post a Comment