Guest post by Philip Bagus

Many politicians and commentators such as Paul Krugman claim that Europe's problem is austerity, i.e., there is insufficient government spending.

The common argument goes like this: Due to a reduction of government spending, there is insufficient demand in the economy, leading to unemployment. The unemployment makes things even worse as aggregate demand falls even more, causing a fall in government revenues and an increase in government deficits.

European governments pressured by Germany (which did not learn from the supposedly fateful policies of Chancellor Heinrich Brüning) then reduce government spending even further, lowering demand by laying off public employees and cutting back on government transfers. This reduces demand even more in a never ending downward spiral of misery.

What can be done to break out of the spiral? The answer given by commentators is simply to end austerity, and boost government spending and aggregate demand. Paul Krugman even argues in favor for a preparation against an alien invasion, which would induce government to spend more. So the story goes.

But is it true?

First of all, is there really austerity in the Eurozone? One would think that a person is austere when she saves, i.e., if she spends less than she earns. Well, there exists not one country in the Eurozone that is austere. They all spend more than they receive in revenues.

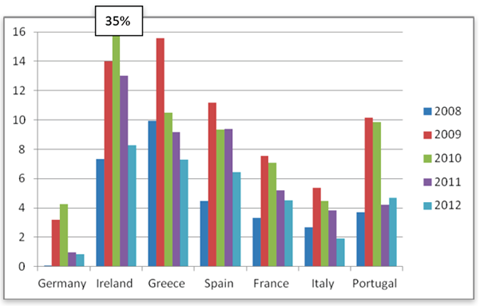

In fact, government deficits are extremely high, at unsustainable levels, as can been seen in the following chart that portrays government deficits in percentage of GDP. Note that the figures for 2012 are what governments wish for…

The absolute figures of government deficits in billion euros are even more impressive:

A good picture of "austerity" is also to compare government expenditures and revenues (relation of public expenditures and revenues in percentage):

Imagine that a person you know spends 12 percent more in 2008 than her income, spends 31 percent more than her income the next year, spends 25 percent more than her income in 2010, and 26 percent more than her income in 2011. Would you regard this person as austere? And would you regard this behaviour as sustainable? Yet this is precisely what the Spanish government has done. It shows itself incapable of changing this course. Perversely, this "austerity" is then made responsible for a shrinking Spanish economy and high unemployment.

Unfortunately however, austerity is the necessary condition for recovery in Spain, the Eurozone, and elsewhere. The reduction of government spending makes real resources available for the private sector that formerly had been absorbed by the state. Reducing government spending makes profitable new private investment projects and saves old ones from bankruptcy.

Take the following example. Tom wants to open a restaurant. He makes the following calculations. He estimates the restaurant's revenues at $10,000 per month. The expected costs are the following: $4,000 for rent; $1,000 for utilities; $2,000 for food; and $4,000 for wages. With expected revenues of $10,000 and costs of $11,000 Tom will not start his business.

Let's now assume that the government is more austere, i.e., it reduces government spending. Let's assume that the government closes a consumer-protection agency and sells the agency's building on the market. As a consequence, there is a tendency for housing prices and rents to fall. The same is true for wages. The laid-off bureaucrats search for new jobs, exerting downward pressure on wage rates. Further, the agency does not consume utilities anymore, leading toward a tendency of cheaper utilities. Tom may now rent space for his restaurant in the former agency for $3,000 as rents are coming down. His expected utility bill falls to $500, and hiring some of the former bureaucrats as dish washers and waiters reduces his wage expenditures to $3,000. Now with expected revenue at $10,000 and costs at $8,500 the expected profits amounts to $1,500 and Tom can start his business.

As the government has reduced spending it can even reduce tax rates, which may increase Tom's after-tax profits. Thanks to austerity the government could also reduce its deficit. The money formerly used to finance the government deficit can now be lent to Tom for an initial investment to make the former agency's rooms suitable for a restaurant. Indeed, one of the main problems in countries such as Spain these days is that the real savings of the people are soaked up and channeled to the government via the banking system. Loans are practically unavailable for private companies, because banks use their funds to buy government bonds in order to finance the public deficit.

In the end, the question amounts to the following: Who shall determine what is produced and how? The government that uses resources for its own purposes (such as a "consumer-protection" agency, welfare programs, or wars), or entrepreneurs in a competitive process and as agents of consumers, trying to satisfy consumer wants with ever better and cheaper products (like Tom, who uses part of the resources formerly used in the government agency for his restaurant).

If you think the second option is better, austerity is the way to go. More austerity and less government spending mean fewer resources for the public sector (fewer "agencies") and more resources for the private sector, which uses them to satisfy consumer wants (more restaurants). Austerity is the solution to the problems in Europe and in the United States, as it fosters sustainable growth and reduces government deficits.

Lower GDP?

But does austerity not at least temporarily reduce GDP and lead to a downward spiral of economic activity?

Unfortunately, GDP is a quite misleading figure.* GDP is defined as the market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a given period, yet this is not at all what it measures.

There are two minor reasons why a lower GDP may not always be a bad sign.

The first reason relates to the treatment of government expenditures. Let us imagine a government bureaucrat who licenses businesses. When he denies a license for an investment project that never comes into being, how much wealth is destroyed? Is it the expected revenues of the project or its expected profits? What if the bureaucrat has unknowingly prevented an innovation that could save the economy billions of dollars per year? It is hard to say how much wealth destruction is caused by the bureaucrat. We could just arbitrarily take his salary of $50,000 per year and subtract it from private production. GDP would be lower.

Now hold your breath. In practice, the opposite is done. Government expenditures count positively in GDP. In our example, the wealth-destroying activity of the bureaucrat raises GDP by $50,000. This implies that if the government licensing agency is closed and the bureaucrat is laid off, then the immediate effect of this austerity is a fall in GDP by $50,000.

Yet as we should understand, this fall in GDP is a good sign for private production and the satisfaction of consumer wants.  Second, if the structure of production is distorted after an artificial boom, the subsequent restructuring necessarily entails a temporary fall in GDP. Indeed, one could only maintain GDP if production remained unchanged. If Spain or the United States had continued to use their boom structure of production, they would have continued to build the amount of housing they did in 2007. The restructuring requires a shrinking of the housing sector, i.e., a reduced use of factors of production in this sector. Factors of production must be transferred to those sectors where they are most urgently demanded by consumers. The restructuring is not instantaneous but organized by entrepreneurs in a competitive process that is burdensome and takes time.

Second, if the structure of production is distorted after an artificial boom, the subsequent restructuring necessarily entails a temporary fall in GDP. Indeed, one could only maintain GDP if production remained unchanged. If Spain or the United States had continued to use their boom structure of production, they would have continued to build the amount of housing they did in 2007. The restructuring requires a shrinking of the housing sector, i.e., a reduced use of factors of production in this sector. Factors of production must be transferred to those sectors where they are most urgently demanded by consumers. The restructuring is not instantaneous but organized by entrepreneurs in a competitive process that is burdensome and takes time.

In this transition period, when jobs are destroyed in the overblown sectors, GDP tends to fall. This fall in GDP is just a sign that the necessary restructuring is underway. The alternative would be to produce the amount of housing of 2007. If GDP did not fall sharply, it would mean that the wealth-destroying boom was continuing as it did in the years 2005–2007.

Conclusion

Public austerity is a necessary condition for private flourishing and a rapid recovery. The problem of Europe (and of the United States) [and New Zealand] is not too much but too little austerity — or rather its complete absence.

A fall of GDP can be an indicator that the necessary and healthy restructuring of the economy is underway.

Philipp Bagus is an associate professor at Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. He is an associate scholar of the Ludwig von Mises Institute and was awarded the 2011 O.P. Alford III Prize in Libertarian Scholarship. He is the author of The Tragedy of the Euro and coauthor of Deep Freeze: Iceland's Economic Collapse. The Tragedy of the Euro has so far been translated and published in German, Slovak, Polish, Italian, Romanian, Finnish, Spanish, Portuguese, British English, Dutch, and Bulgarian.

See his website.

This article first appeared at the Mises Daily.

* GDP is a completely misleading figure. The metric of GDP, so-called Gross Domestic Production, would be more accurately titled Nett Domestic Consumption—since it measures all consumption spending, including every dollar spent by the governmet, yet only a small percentage of spending undertaken on production. “In that light, the desire to boost debt-based consumption via the creation of artificial demand seems much more questionable.” See Mark Skousen: “Consumer Spending Drives the Economy?”

1 comment:

Austerity opponents always suggest raising taxes is part of austerity. This is like a family suggesting that they are having budget problems so they are going to ask for a raise or a business losing money raising their prices. That is not austerity. There are a number of great studies showing growth is inversely related to government expenditures.

Post a Comment