Historian Scott Powell suggests there's a cogent reason both for all those wars that have regularly overrun Europe, and also for Europeans' general dislike of America -- in a word, Europism:

Historian Scott Powell suggests there's a cogent reason both for all those wars that have regularly overrun Europe, and also for Europeans' general dislike of America -- in a word, Europism:

“European Subordinacy” (mostly to America) has generated a cultural backlash rooted in the only outlook that Europeans seem to know: collectivism. Since this cultural coping strategy is now continental in scope, I call it “Europism."

To explain what he means about Europe's general collectivism, we need to take a short detour through the word "qua," which means "in the capacity or character of; by virtue of." The word was very  popular with our old friend Aristotle, who described metaphysics as "the science of being qua being" -- which is about as much as you need to know about metaphysics for this post, but you can begin to see how the word might be used.

popular with our old friend Aristotle, who described metaphysics as "the science of being qua being" -- which is about as much as you need to know about metaphysics for this post, but you can begin to see how the word might be used.

Anyway, "Europism," says Scott, "is rooted in the dismal historical record of European people living as separate, antagonistic tribal and national groups."

From the earliest time of the barbarian migrations, to the nineteenth century and twentieth centuries when Germany, Italy, and the various Slavic nations were formed, Europeans have had virtually no grasp of “man qua man.” They’ve always seen themselves as man qua Briton, or man qua Salian Frank, and later man qua Aryan, and man qua Serb, Bosnian, Croat…

... Or Kosovar. No wonder Europe has endured centuries of essentially tribal warfare. "This myopic outlook has proven to be a terrible handicap," he explains, "Only a greater enemy could ever bring [these disparate groups] together." Which, today, is America's role in Europe. Even the Reformation never changed the tribalism much -- the tribes just became ever more Balkanised.

... Or Kosovar. No wonder Europe has endured centuries of essentially tribal warfare. "This myopic outlook has proven to be a terrible handicap," he explains, "Only a greater enemy could ever bring [these disparate groups] together." Which, today, is America's role in Europe. Even the Reformation never changed the tribalism much -- the tribes just became ever more Balkanised.

In the wake of the Reformation, when man qua Austrian vs. man qua Prussian, came to mean man qua Catholic Austrian vs. man qua Calvinist Prussian, and man qua Englishman vs. man qua Frenchman was exacerbated to become man qua Anglican Englishman vs. man qua Catholic Frenchman, the impediment of collective self-identification only intensified.

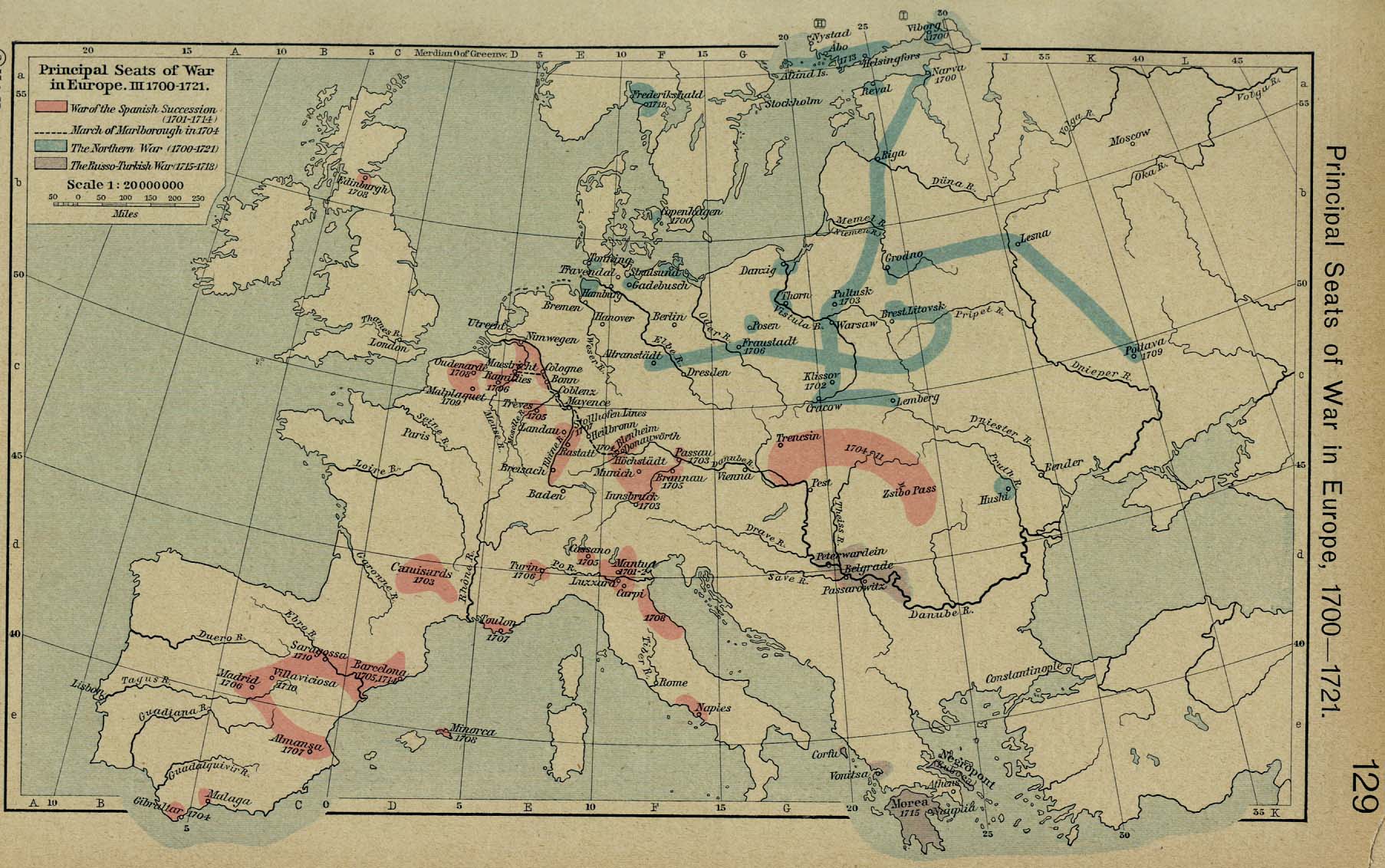

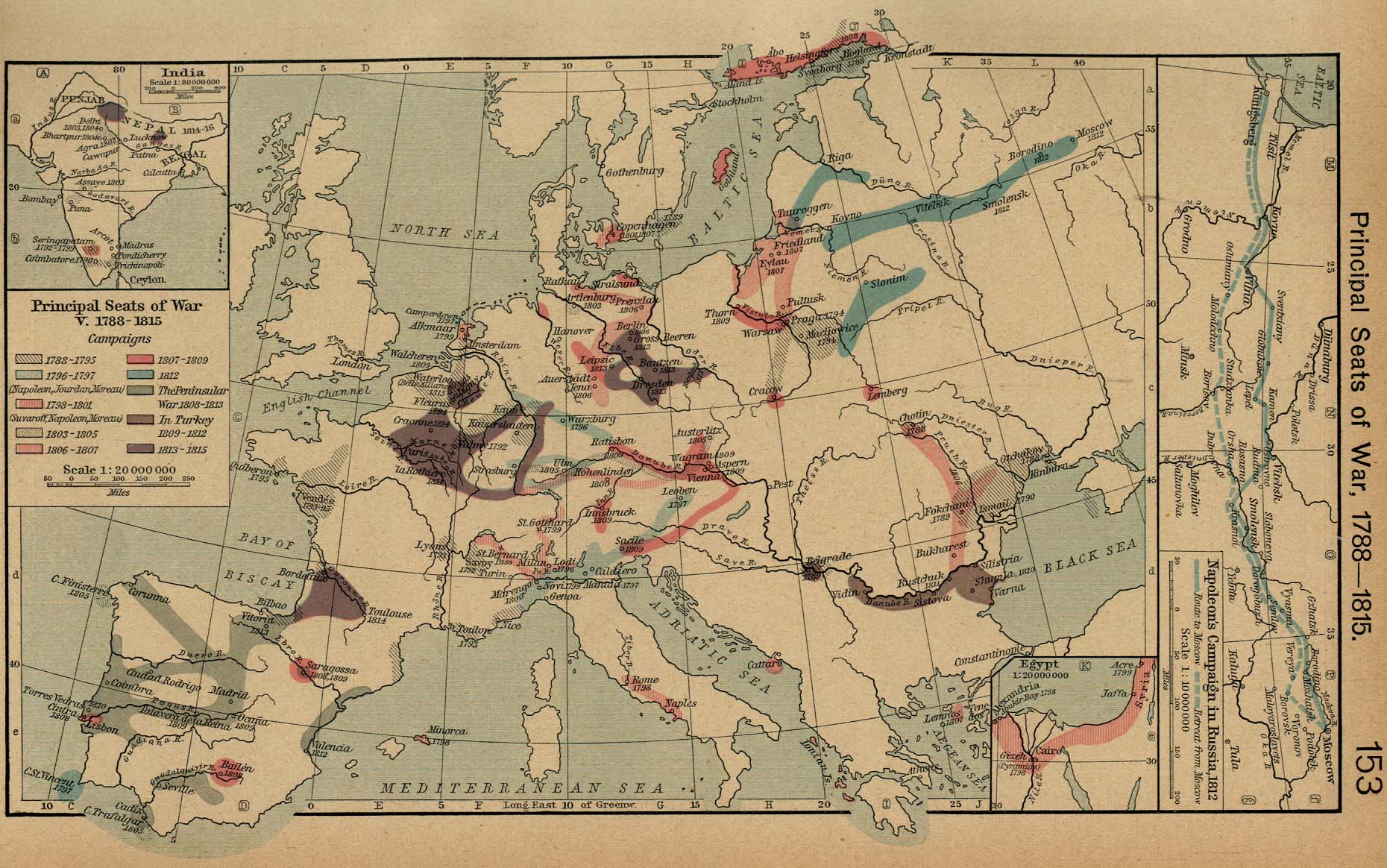

It got so bad that Europeans were killing each other almost non-stop in some quarter of the continent during the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries.

If you're wondering what all those maps down the side represent, it's the "pri ncipal seats of war" across Europe from 1618 to 1815. Not a pretty sight if you like a peaceful life. [Thanks to the Perry-Castañeda Library at the Uni of Texas you can click to enlarge the maps.] And if you want to understand the real roots of all those wars, and indeed of war itself, it's this idea of people as part a group, rather than as individuals with the right to exist for their own sake. That was the distinctive American contribution to human affairs, and the basis on which the country was founded. No wonder it's so easy for Europeans to dislike, and to misunderstand.

ncipal seats of war" across Europe from 1618 to 1815. Not a pretty sight if you like a peaceful life. [Thanks to the Perry-Castañeda Library at the Uni of Texas you can click to enlarge the maps.] And if you want to understand the real roots of all those wars, and indeed of war itself, it's this idea of people as part a group, rather than as individuals with the right to exist for their own sake. That was the distinctive American contribution to human affairs, and the basis on which the country was founded. No wonder it's so easy for Europeans to dislike, and to misunderstand.

Anyway, I highly recommend reading and digesting Scott's post -- it will help you understand several centuries of human history.

And given his principled approach to history, you might also begin to understand why I'm enjoying his online history course so much.

UPDATE: Part Two of Scott Powell's article is now up at his blog. Enjoy.

2 comments:

True Pc, true.

But you must remember that it was from Europe that Individualism grew in the first place. Indeed today, it seems many European nations (Britan and Scandinavia excluded), even the ex-commie ones, are far ahead of America when it comes to libertarian thought.

Consider though that the apparently "benighted" European cultures grew up in parallel with each other, hip to hip.

Commercial competition and war was/is inevitable.

Arguably, if you follow Jared Diamond's thesis, the jostling contributed to Europe's ascendancy.

On the other hand, immigrants to America were able to transplant the best of the Old World and incubate its growth in a massively fertile new land.

The chance of fratricidal competition from the outset was massively reduced.

It's not an even comparison.

As a counter-factual, if the native Americans had equivalent technology to the incoming Europeans do you think the colonisation would have progressed as smoothly.

I imagine your war maps would look rather different.

Post a Comment