The first thing you notice through the fog of sleep is a loud, ringing sound. As you rise up through the fog of sleep you recognise it as an alarm of some sort. Your alarm clock. You focus further and realise that it's not going to turn itself off. As you force yourself awake you direct your focus to your limbs, lifting yourself out of bed, and you turn off the clock on your way to the bathroom, making yourself shake the sleep from your mind as you go. It's the start of another day.

The first thing you notice through the fog of sleep is a loud, ringing sound. As you rise up through the fog of sleep you recognise it as an alarm of some sort. Your alarm clock. You focus further and realise that it's not going to turn itself off. As you force yourself awake you direct your focus to your limbs, lifting yourself out of bed, and you turn off the clock on your way to the bathroom, making yourself shake the sleep from your mind as you go. It's the start of another day.As you shower, you set yourself thinking about what you need to do today and, as you do and as you shower, the scales of sleep slip ever further away. You understand you have an important day ahead, and you feel yourself rising up to meet it. In a few short minutes, by your own direction, your mind has changed from an inert unconscious thing, one barely able to grasp what's going on around it, to one that is now focussed upon the events of the day and is starting to make plans to meet them ... and all this even before the first coffee!

Most of us manage this process in a few minutes. Some take hours. Some will choose to stay unfocussed for days. But everyone who has ever experienced this -- which is all of us, at some time -- has experienced what it is to have free will.

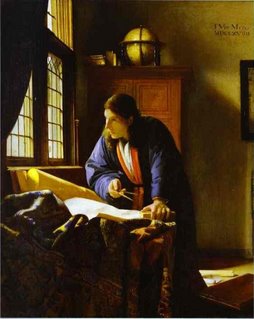

Free will at its root is that process of choosing to focus, of deciding first of all to lift our level of awareness from a lower level to a higher one (or to decide not to) , and then directing our focussed attention to something on which we've determined we need to pay attention. A lecture perhaps. A book. A piece of music. A blog post on free will. Someone offering us a beer. At each stage of listening, reading, comprehending, trying to grasp a thought (as Vermeer's Geographer is doing in the picture above) we can choose to maintain attention and focus on what we're trying to take in, to weigh the thoughts and melodies and information that is coming in, or we can choose to float off in a vague fog and let everything just wash over us. The act of choosing to pay attention is a volitionally focussed act by which we first say to ourselves, "I need to focus on this, to understand this," and then acting -- choosing to act -- so as to direct our minds to that on which we ourselves have determined that we need to understand.

As I've described above, the act of focussing is voluntary, and is almost like continually turning on a car. At each stage we can choose to go either to a higher level of awareness, or not; we can choose to focus, or we can choose to drift back off either to sleep, or into a state of unfocussed lethargy. You can lead a horse to water but you can't make it drink. Equally, you can lead someone else's brain to stimulus, but you can't make it respond. That person must do that work for themselves.

Volition is a powerful factor. Thoughts, values, principles are not something given to us, or imprinted upon us; rather, they are things to identify and think about and grasp for ourselves. Or not. No one can do the thinking for someone else. With sufficient will we can work towards grasping the highest concepts open to us, or we can even sleep through the ringing of our alarm clocks. That choice -- to focus or not; to switch on or not -- is contained entirely within ourselves, and from that choice made by each of us every minute of every day all human thought and all human action is the result. The fact that we are continually making this choice (or choosing not make it) every waking minute of every working day is perhaps why we sometimes fail to see that we're doing it, we've almost automatised our awareness of it, but honest introspection (if we honestly choose to do so) is all it requires to be identified.

This is the nature of the volitional consciousness we each possess, and the fact those who choose to deny free will wish to evade: that this great thinking engine resting on top of our shoulders does not turn itself on automatically. We ourselves own the keys to the engine, and it is in that fundamental choice -- to think, or not to think; to focus, or not to focus; to go to a higher level of awareness, or to drift in and out of awareness -- that the faculty of free will itself resides.

So given that very brief discussion of free will -- to which, if you like, you can add previous similar discussions here, here, here, here and here -- what then do you make of this discussion currently under way at the Humphrey's blog:

What do you make of that? "If there's no God then there's no free will"? If you're an atheist, then "logically" -- logically? -- you can't "believe" in free will? As I've suggested above, we don't need to "believe" in free will in the same way a Christian chooses to believe in the existence of a supernatural being; instead, to identify that we do have the faculty of free will, we can simply introspect and identify ourselves engaging in acts of free will. (Indeed, you can do it right now as you weigh in your mind that last thought, and choose whether or not to accept it -- or whether to evade the effort or the knowledge. And recognise, dear reader, that if you choose not to accept it or to evade it, you've still made a choice.)Where does this thing called free will come from?

"...if there is no God there’s no free will because we are completely phenomena of matter... we cannot be considered morally responsible beings unless we have free will. We do everything because we are controlled by our genes or our environment."

- comments by David Quinn in The God Delusion: David Quinn & Richard Dawkins debateLogically, if you are an atheist, you will believe that we are completely influenced by our genetics and environment. That there is no free-will, that moral responsibility has no ability to manifest in any human being. If you don't believe all of that, then you cannot be an atheist and you must have some inkling that God exists.

So much for needing to believe in the supernatural in order to "believe" in free will. How about the claim that we are "completely phenomena of matter" as Mr Quinn suggests? Well, no. We're not. The way our mind is constituted has produced what we know as consciousness. We are not just a bunch of chemicals: we are a particular being with a particular make-up, the manner in which each of our brains are 'wired' has produced consciousness in each of them. As Ayn Rand identified:

That which you call your soul or your spirit is your consciousness, and that which you call your "free will" is your mind's freedom to think or not, the only will you have, your only freedom, the choice that controls all the choices you make and determines your life and your character.We have consciousness. Consciousness is endowed by its nature with the faculty of free will. What we each choose to do with our own consciousness is up to us -- and it's there that the discussion of morality really begins...

LINKS: Nature v Nurture: Character is all - Not PC

The chemistry of love - Not PC

The fatalism of entropy. The dynamism of spontaneous order - Not PC

More on value judgements in art - Not PC

Excusing the 'bash' - Not PC

Man and free will - Lucyna, Sir Humphrey's

RELATED: Philosophy, Ethics, Religion

14 comments:

I still don't see how you can argue for free will via introspection. The whole reason the free will vs. determinism debate came about was from the observation that the appearance of making choices and having free will is consistent with both having free will and not having free will.

No-one denies that it feels like we have free will; that we observe ourselves seeming to make choices - the point is that this is not enough in itself to prove that we do.

Aye, it seems that people still think that we have some priviliged access to our own mental states that is both omniscient and infallible, even though we can produce counter-examples to both those kinds of claims.

"The Hand of Morthos said...

Aye, it seems that people still think that we have some priviliged access to our own mental states that is both omniscient and infallible, even though we can produce counter-examples to both those kinds of claims."

Claim you have evidence and producing it are two different things!

BTW your position is self-contradictory. If we can not know our "true" mental states then it is impossible to test if we know our mental states...

Sean.

Sean. If you are going to use the word 'contradictory' then I would ask that you know what it means. You might have meant 'contrary,' which has a different meaning. What I present is not a contradiction. It is demonstratably easy to show that we can be confused as to our mental states.

Say I am at my desk, reading a book on epistemology, holding the belief that I am reading the book (and, it turns out, I am actually performing all the actions we assume come from holding such a belief) but it turns out that I am simply going through the motions and reading whatsoever. Where someone to come up to me and say 'Morthos, what art thou doing?' I would reply 'Sir, I am reading this most excellent tome!' Yet, if I was challenged to say what it was I was reading I would soon realise that I had not been reading at all.

Now an obvious response is to say that I am confused at this point and that I wasn't reading. Fair enough, but, but I held the belief that I was reading and it turns out that I was wrong to hold that belief. Perhaps I was *reading (where *reading is an action that has all the features of reading but plays no informative role). Maybe so, but I still believed I was reading when I was *reading.

This seems like a challenge to the thesis of priviliged access to mental states. It shows both that I am fallable in my beliefs about mental states.

Can I be non-omniscient about mental states (can I, for example, have a mental state that I don't know about or be conscious of)? Plausibly, yes. A trivial example might be that I have always boasted that I would volunteer to fight against an enemy that threatened my country, only to find that as soon as a threat appears I find myself filled with fear and refuse to join the armed services. Previous to this moment I thought I knew my own mettle, but it turns out that I do not. More sophisticated examples revolve around belief compartmentalisation; I claim to be a material determinist yet when confronted with the teleporter thought experiment I find myself unwilling to choose teleportation over using the spacecraft and thus admit to a previously unacknowledged belief in a non-material aspect to my personality.

All of these show that we should be fallibilists about mental states because it is quite plausible that we might be wrong in some of our claims about our own mental states.

So what?

Just because you are (not you personally) fallible doesn't obliterate the potential of true discovery through introspection. Next you will be saying science is hopeless because it doesn't get it 100% correct first time every time instantanously! This absurd standard of perfection is a blatant rejection of reality.

Sean.

Sean, Brian S is right (and, by inference, so is Morthos); if we can show that we are prone to error regarding our knowledge of our mental states then we should be fallibilists. To claim that we could one day truly know our own mental states without possibility of error is a nice sentiment but unless you have a theory as to how that might be possible the counterexamples already presented do imply that we should remain fallibilists and be prepared to admit that introspection doesn't give us priviliged access to our own mental states.

HORansome said...

Sean, Brian S is right (and, by inference, so is Morthos);

Maybe you should reread the posts. Brian S seems closer to my position than Hand's. Remember I am not claiming perfection as the standard. Just because we are not always right does not mean we are always wrong. Nor that we can improve our understanding etc.

Sean

AAHHH,

That should be,

"Nor that we can NOT improve our understanding etc."

Sean.

I tihnk the problem here is that you are mistaking fallibilism for some much stronger error theory.

My understanding of fallibilism may well be a moot point. But the core of the matter is this; I asked for a data set of evidence that disproves introspection as a valid tool. A data set was produced (and that is being kind, it was antedotal speculation at best), but it in no way resembled the requested data set.

Sean.

Well, Sean, let us hope that you never decide to engage in the great discipline we call Science, since your selectivity of evidence for or against a view is sadly lacking in what we would call rigour. What, exactly, is wrong with the examples Morthos gives? They certainly show that introspection only gives us fallible knowledge of mental states, and fallible knowledge of mental states implies that we can never be absolutely certain of our own mental states, a position contrary to that which you first expressed. Either explain why you think these examples are lacking or be prepared, as a rational agent, to be amendable to the idea that you might well be wrong in this matter.

With respect, it is I that is asking for an actual data set, not rationalistic musings. That is science - the union of theory and evidence, not simple thoughts.

Further, I never claimed that we have absolute access/knowledge/omniscience to our mental states. To claim that I have is intellectual dishonesty. I simply stated that the objection raised is in no way a killer blow to the thesis presented. I do not require this absurd/false ideal of perfection before I get out of bed in the morning. Just because we can be wrong does not mean we are always wrong.

Even in Hands confused examples it was clearly possible to correct the error through active introspection. Indeed, the example given seems a mistake of not actually introspecting rather than introspecting and getting the wrong data.

Essay question: Take the following two quotes from Sean:

'Further, I never claimed that we have absolute access/knowledge/omniscience to our mental states. To claim that I have is intellectual dishonesty.'

and:

'If we can not know our "true" mental states then it is impossible to test if we know our mental states...'

--

Now who is being intellectually dishonest. Why, it must be the person who said:

'With respect, it is I that is asking for an actual data set, not rationalistic musings. That is science - the union of theory and evidence, not simple thoughts.'

I presume you don't know much about the development of the Theory of Mind and the associated work in neurobiology; thought experiments such as those I presented are the bread and butter of Theory of Mind discourse because they present plausible counter-examples to the thesis of priviliged access to the mental. These are not mere anecdotes but examples of how we can show ourselves to be mistaken in re our own mental states. Once we admit that are can be mistaken we have to accede to the idea that the possibility of error in re mental states is high. This doesn't require us to doubt all and every mental state but it does cast suspicion upon them. I see that your frequent reply to this is simply 'Yeah, but that doesn't mean we are always wrong.' True, but you inane comment does nothing to add to the discourse whatsoever.

As to your claims about active introspection (the term in common use is 'attentive introspection', by the way); the whole point of my examples is that even if we do think that the example of my *reading is a failure to be attentive we still have the second order problem that I mistook my *reading for reading, and if you want to run the attentive distinction then you fall into an infinite regress.

Now, since you haven't actually added anything to the debate for the last few posts and I've just been wasting chunks of my otherwise precious time repeating myself I shall consider this matter closed.

You don't find it ironic, Morthos, that you're using your obvious intelligence to deny the obvious with respect to existence and about consciousness rather than using it to draw conclusions about the obvious to take your knowledge further?

Post a Comment