The facts are clear, there is one way and one way only in which inequality has surged in NZ:

Sources: Newspaper Reporting on Inequality: Bryce Edwards, 2014.

http://liberation.typepad.com/Liberation/2013/12/the-politics-of-poverty-in-new-zealand-Images-.HTML;

Inequality: Christopher Ball and John Creedy, 2015.

Http://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/research-policy/wp/2015/15-06/twp15-06.PDF

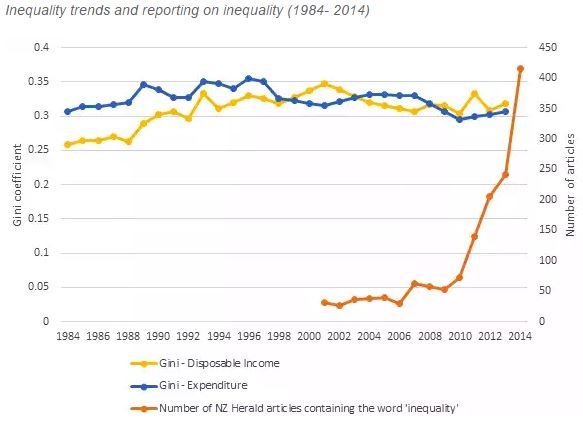

From a standing start in 2001, articles about inequality have been going through the roof, while actual inequality has … well, not changed very much at all.

The actual fact of an almost static figure for inequality over the last three decades hasn’t stopped commentators talking about it like a house on fire – which, as today’s report on inequality by the NZ Initiative makes clear (from which the above graph comes), may be the appropriate expression. Because, say the report’s authors, while

it is difficult to make sense of the increasing public concern with inequality if we look only to income or wealth statistics, there is a massive inequality concern that is rightly troubling many New Zealanders: housing.

In short, New Zealand’s ‘inequality crisis’ is really a housing crisis.

Inequality after housing costs is significantly higher than before housing costs. While incomes have risen for high and low earners, the rising cost of housing especially hits the poor.

Whereas the gains in rising housing prices are captured by those who aren’t. Primarily, by those who bought early and have borrowed the most.

The graph below shows the differential effect of rising housing outgoing-to-income ratios (OTIs) across income quintiles (where quintile 1 is poorest and 5 is richest). The proportion of households with OTIs greater than 30% rose markedly between 1998 and 2015 for each of the bottom three quintiles. In contrast, it was the same in 2015 as in 1998 for the top quintile.

Source: Bryan Perry, "Household Incomes In New Zealand: Trends In Indicators of Inequality and Hardship 1982 to 2015," (Wellington: Ministry of Social Development, 2016), Table C.3, 55: Proportion of Households with Housing Cost OTIs greater than 30%, By Income Quintile.

In the book Equal Is Unfair, Yaron Brook and Don Watkins argue that

one of the problems with the concept of “economic inequality” is that it lumps together two fundamentally different things: inequality that reflects differences in productive achievement and inequality that reflects some people’s ability to gain unearned wealth. Package-deals like this lay the groundwork for injustice.

The Cantillon Effect decribes the process by which “an expansionary monetary policy constitutes a transfer of purchasing power away from those who hold old money to whoever gets new money.”

But who are the first receivers of the new money in our fiat money system? Those who want to benefit from the new money must receive it where it is produced, namely in the banking system in form of a loan. And in order to get a loan from a bank it is helpful to be rich. Rich people owning large amounts of assets such as stocks or real estate may pledge their stocks or real estate as a guarantee for new loans. They may then use these loans to acquire even more stocks and real estate that, in consequence, keep rising in value.

So in other words,

- where we have an inequality crisis at all, it is actually just another symptom of the housing crisis; and

- the prime beneficiaries of the housing crisis are the already-housed who are ready borrowers; and

- housing aside, the only place in which ‘inequality’ has exploded is in the times the commentariat has commented upon it.

.

1 comment:

Another thing you'll be shocked, shocked to learn is that inequality and poverty articles make contortionist moves to avoid mentioning social welfare, in case the elephantine question of whether it alleviates of exacerbates the situation is spotted in the room.

The authors you mention are spot on about the effect the money-supply expanding reserve banking cartel have on the propertied versus the not-yets.

Post a Comment