[UPDATE: Oops, forgot to add the link to the excellent online Early NZ Books archive at Auckland University, so you can do lots more reading yourself. Send me the best bits you find…]

I came across the following story related in James Stack’s memoirs ‘Further Adventures in Maoriland,’ a recounting of the tales of a young missionary in nineteenth-century New Zealand, and a great politically-incorrect title. The story recounts the manner of how at least some of Ngai Tahu’s original full-and-final payments for land were dispersed, and how communal ownership works in practice.

Consider it as a humorous and topical cautionary tale on the huis-and-communes methods of management foisted on us all by the likes of the RMA and various ministries.

Imagine the spectacle of the ship sailing up and down the bay for days while huis were held to decide how to anchor it. Imagine it, and contemplate that there are folk today who would like to make that a symbol of your future, and mine…

Chapter VIII

”In which is related the authentic and diverting tale of the ship that sailed into Port Levy with forty Maori skippers aboard her.

“We [came across] two things while strolling along the beach, which had attracted our notice and caused us some surprise. One was the hull of a good sized coasting vessel, weather worn, but apparently quite sound, lying on the beach and, close beside it, a quantity of valuable machinery, exposed to all weathers...

“[We were told that] the Maoris [imported] from England the machinery we saw. It was intended for a first-class flour mill, to be erected at Port Levy. When it arrived at Lyttleton, the whole Maori population of the Bay came to take delivery of it, and there was great excitement amongst them when the heavy machinery was being placed in boats, for conveyance to their settlement.

“The purchase money of the machinery was not contributed by the Port Levy Maoris only, but by some whose largest interests were at Kaiapoi. When the question of a site for the erection of the mill came to be discussed by the several owners, they all disagreed. Some wanted it in one place and some in another, until at last the most enthusiastic advocates of mill-building lost all interest in the subject, and refused to allow anyone else to do anything, with the result that in time it was totally destroyed by exposure to the weather.

“The fate which befell the little vessel we saw abandoned on the beach was another instance of the evils of divided ownership and should serve as a warning to those theorists amongst ourselves who wish to substitute communism for individual ownership of property.

“The vessel was purchased with a sum of six hundred pounds, which the Maoris received from land sold to the Government. They counted upon its proving a very useful and profitable investment. It would, they thought, enable them to visit their friends in Otago and Stewart’s (sic) Island, and take to them flour, bringing back from them mutton birds and dried barracouta, and so save money which they now spent in freight and fares.

“The vessel was handed over to them in Lyttleton, where about forty men women and children got on board as soon as they obtained possession of it. Several of the number were experienced sailors, but they were not allowed to take control of the craft on that account, for fear they might acquire superior rights of ownership and dictate to the others what ought to be done with the new purchase. The result was that everyone on board asserted his claim to a share in the ownership by doing something to get the vessel under way, and to sail her around to Port Levy.

“All might have gone well but for a violent south-westerly gale which suddenly overtook them before they reached the Heads, and threatened to drive them out to sea. This was a prospect which filled them with great alarm, for they might all lose their lives if cast adrift in the state their little vessel was in.

“They hugged the shore as they rounded Adderley Head, and hoped to anchor under the shelter of the high land. Someone heaved one of the anchors overboard, and, to the surprise of everybody, the whole of the chain attached to it ran overboard too, and fell into the sea. Without taking the precaution to examine the fastening of the cable attached to the second anchor, it was also thrown overboard, and with the same result, and both anchors were lost. There was a tremendous hubbub, everybody blaming everybody else for “what had happened. In the meantime the vessel was within a few feet of the Port Levy reef of rocks, upon which it escaped being wrecked more by good luck by good management.

“By the aid of long oars they turned the vessel around, and beat down the bay. When opposite their village however they could not communicate with the shore, as they had no boat with them, and the loud storm drowned their cries. The onlookers, gathered on the beach, and expecting to see the anchor dropped, now saw with amazement that this eagerly expected craft, their communal property, was being sailed back towards the Heads. It sailed back, but again it turned; and so it continued to be navigated backwards and forwards, up and down the bay. At last it grew quite dark, and the villagers retired to their habitations to talk things over. Next morning , at break of day, there was a very excited crowd of Maoris on shore. There was the vessel, still sailing up and down the bay, and why it should be doing so, for no apparent purpose, puzzled them all very much. At last they came to the conclusion that all on board must be very drunk, for none but idiots could behave as they were doing.

“Curiosity to solve the mystery induced several men to put off in a whaleboat, and board the vessel the next time she approached the village. On their return they were able to inform the waiting crowd that both anchors and both cables were lost overboard, and that he only way to escape being wrecked was to keep sailing about until fresh anchors and cables could be procured.

"After parleying as opportunity arose, it was decide that, while those who came in the boat should remain on board and continue to sail the vessel, the others should discuss what was to be done. Angry recriminations followed. Anchors and chain cable were very expensive, and the general feeling was that the cost of providing new ones should be borne by the persons through whose folly they were lost. But they stoutly contested their liability. The discussion of the question was so prolonged that the sailing crew had to be relieved and renewed day after day, until at last everyone got sick and tired of the job. The climax was reached when one evening the sailing crew decide to anchor the vessel with a boat’s anchor, and go ashore to sleep. During the night an easterly gale sprang up and drove the craft on to the rocks where she bumped all night long, and was found in the morning lying on the beach with a large hole in her side. There she was allowed to remain for years because her multitude of owners could come to no agreement about the payment of the necessary repairs.”

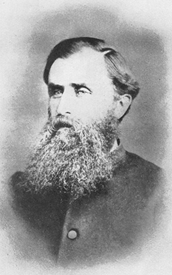

He was born in a tent in a Maori pa at Puriri, Thames, New Zealand, 27th March, 1835, was the oldest of seven children of the missionary James Stack and his wife, Mary West. He died at Worthing, Sussex, England, 13th October, 1919.

His beard and bearing would now earn him free drinks in any bar in Kingsland any night of the week.

You can find Stack’s book and many more early NZ histories in the online Early NZ Books archive at Auckland University.

The italics in the piece are mine.

1 comment:

That was a good read. So was the other bit about Stack having the politician's/minister's curse of accepting "hospitality" by drinking all manner of crappy tea! That's another comedy skit right there.

Am now up to the bit where his wife writes about the haka...

It struck me as curious that,

whilst the missionaries have got the war dance abolished,

owing to its exciting and degrading influence upon the

natives, their Christian countrymen were always wanting

the Maoris to show them what it was like. From what

little I saw of it, the sooner it is lost sight of and forgotten,

the better for everybody.

Post a Comment