Speaking of problems with innovative building – barriers to using the sort of building techniques that makes homes affordable for first-time buyers, and profitable for speculative builders to build for them – a recent NZIER report into the barriers to innovation in housing found that the problem is not builders or buyers, both of whom would be happy to innovate, but … well, I’ll let the report speak for itself:

The regulatory environment and building consent authorities are the top barriers to innovation and productivity.

I swear I did not write that sentence myself. But I did make it larger and bolder so that even regulators and building consent authorities can read it.

Be aware that the report is not looking at the cost of regulating land, only at

the drivers of demand for bespoke housing, the impact of building firm size and the barriers to innovation, and thus productivity, in New Zealand residential construction.

“Bespoke” housing is just a fancy word for housing that isn’t mass-produced. Here’s a short summary of the report’s findings:

Regulation is a key barrier to innovation: for the most part regulation (in a very general sense) is seen as frustrating and constraining the industry’s ability to adopt new innovations or imposing excessive costs..

- regulatory requirements impose costs that are larger than their benefits. Some builders lament the lack of cost-benefit analysis to help safeguard against bad regulations and guidelines

- builders are frustrated that they have very little leeway to think for themselves and must conform to detailed plans to the nth degree, let alone be innovative. The introduction of licensed building practitioners increased costs but allegedly did not increase flexibility

- barriers to importing new materials and difficulties in proving to building consent authorities (BCAs) that novel materials meet the Building Code (despite having passed through more stringent regulatory assessment overseas)

- what could be a lack of simple utilitarian approaches that are Acceptable Solutions for building, which would improve affordability. For instance, allowing standard plasterboard to be laid vertically on walls and nailed in, rather than specialist and more costly products that require more staff handling and logistics complications

- the role of joint and several (i.e. ‘un-proportional’) liability as underpinning risk aversion and the barriers to innovation, particularly from BCAs

- how regulations are implemented is sometimes more critical than the rules themselves; for instance, Resource Management Act (RMA) pre-application meetings, which are meant to expedite resource applications, can lead to planners micromanaging developers, for example specifying letterbox styles and the colours of the front doors…

- Some stakeholders were frustrated over barriers to importing new innovative materials and products. We understand that there may be a gap between perceptions and reality about how easy it is to import new products under existing regulatory regimes. But new product developer perceptions of importation hurdles, builder and designer norms and BCA practices govern what is done. There appears to be a potentially important role for government to ensure mechanisms to bring new products to markets are simple, cost effective, well understood by the building industry and consistently applied by BCAs.

- Building practitioners in the first instance bear the cost of regulations, policies and guidelines…

- [It is] not apparent that benefits exceed costs of regulation. Engagements with builders and buyers has revealed recent regulation changes that have imposed costs, and it is not clear at all whether there are benefits that more than offset these.

For instance, one builder estimates the enforcement of scaffolding regulations cost the industry and consumers around $300 million per annum to solve what MBIE estimates is a $24 million per annum problem…

A house buyer in Christchurch estimates that the ramped up regulatory requirements on house foundations cost him an extra $100,000 dollars.

We understand that proper cost-benefit analyses were not undertaken prior to these regulatory changes.

Many builders were of the view that cost-benefit analysis should apply to existing and new regulations, guidelines, or anything else perceived by the market as being a regulation.

The reports authors fault the regulations, not the regulators, particularly the imposition of “joint and several liability,” --- “the legal rule that could have [folk] being liable for all the damages caused by other parties if they contributed to the same loss, regardless of their proportional contribution.”

- It is understandable that local authorities are risk averse as they try and avoid a repeat of liability for leaky buildings. We note that the Law Commission has recommended retaining joint and several liability, which tends to pass liability back to councils. This is in contrast to Australia, where people are liable only for the proportion of the damage they caused…

- We found that systemic risk aversion is curtailing innovation and potential productivity gains throughout the residential building sector as local authorities try to avoid liability as the last party standing (the “deep pockets” issues).

- Of the builders that were aware of joint and several liability, they viewed it as having a chilling effect on investor confidence and morale in the industry. They saw it as being a key causal factor in the excessive risk-aversion by BCAs.

Some builders saw joint and several liability as a key reason why BCAs are so risk averse, and thus act as such a barrier to innovation and productivity.

The majority of builders had little or no understanding of joint and several liability — the legal rule that could have them being liable for all the damages caused by other parties if they contributed to the same loss, regardless of their proportional contribution. When informed of this, they thought it was outrageously unfair and inappropriate.

Some builders believe it would reduce the supply of builders in the industry (relative to proportional liability like in Australia).

Summary:

The regulatory environment and building consent authorities are the top barriers to innovation and productivity

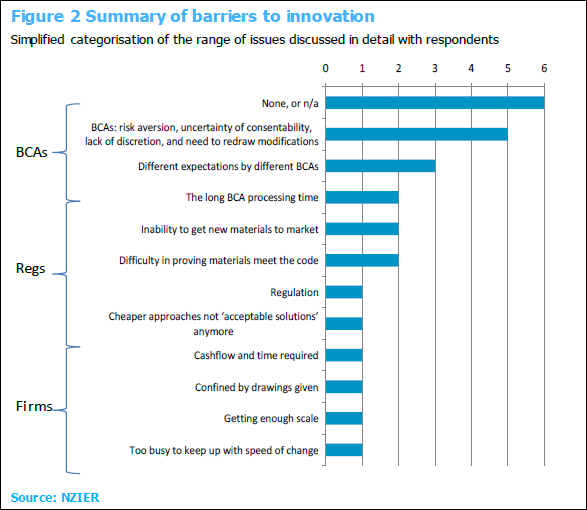

The main barriers to innovation described by builders (as indicated in the figure

above) are:

- Building Consent Authorities (i.e., BCAs i.e., councils): excessive risk aversion, consent uncertainty and lack of discretion, the need to redraw changes, different approaches across BCAs, and long

times to process consent applications and inspections- solutions that meet the building code: barriers getting new materials to

market, difficulty in proving to BCAs that novel materials meet the code,

older building approaches that are quaint but safe and healthy are

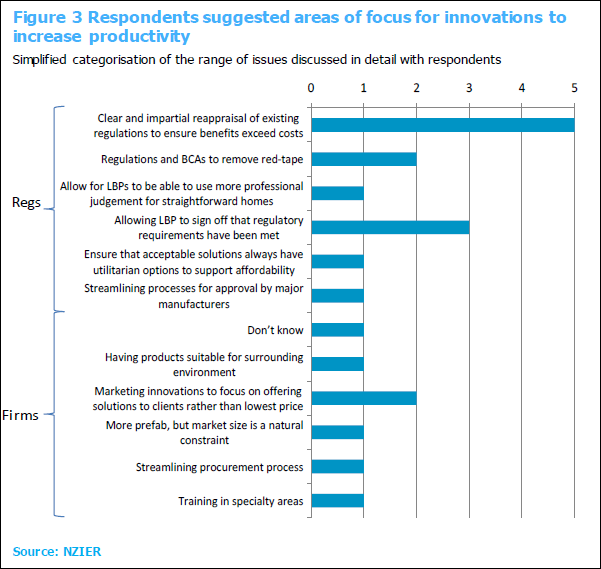

apparently no longer acceptable Alternative Solutions…The recommendations to improve productivity are related not to firms but to regulation [see Fig. 3 below]. Many builders questioned whether certain regulation changes that imposed cost were worth it. They suggested ways to reduce time, reduce red tape, delegate more authority, and ensure Acceptable Solutions support affordable housing. For instance:

- builders want cost-benefit analysis to be applied to all existing and new regulations and required practices

- licensed building practitioners have faced higher costs but not commensurately higher authority to sign off on work; they want to be given more leeway to exercise professional judgement

- a view was expressed that Acceptable Solutions should include utilitarian approaches to help ensure affordability. There has been creeping up of minimum standards and practices that provide greater utility at a greater cost, whereas less aesthetically pleasing approaches have dropped off the list of Acceptable Solutions without evidence they did not perform.

Bear in mind this is a mainstream report with, if anything, a tendency to assume government regulation is necessary, so for them to come to conclusions even as tepid as they do is heartening, if not necessarily a harbinger of anything different.

You can read the full report here.

****

Just as interesting as the report’s conclusions were the reactions to the report – and the inability to comprehend those conclusions.

From the ill-named Ministry of Business, Innovation Etc.: “This new research by NZIER…indicates that better project management and changing the way building regulations are set and applied provide the greatest opportunities for improvement.”

You’d think all we need is a little tinkering. And no real sign of the report’s main conclusion that “the regulatory environment and building consent authorities are the top barriers to innovation and productivity,” except in the way regulations are “set.”

From BRANZ, the government’s gatekeeper for innovative building systems: “Innovation in residential construction in New Zealand focuses on the use of new products that enhance building design but don’t necessarily improve building industry productivity. This was among the conclusions of a recent report prepared for BRANZ and the Building and Construction Productivity Partnership by the New Zealand Institute for Economic Research (NZIER).”

You’d almost think innovation was a dirty word.

From Lawrence Yule, the head of Local Government NZ (i.e., the BCA’s union), was a comment that almost makes you think he didn’t read the report, which he claims “found demand for bespoke housing, poor project management and slow uptake of technology were factors in slowing productivity in the building sector.”

In other words, it’s home-buyers wanting innovation wot makes innovation so difficult.

And from the government itself, not a word.

Ironically, the report itself was co-commissioned by BRANZ, and the joint press release that announced its release ended with the bald statement:

Most of the report’s recommendations are already being implemented.

They did not say by whom.

No comments:

Post a Comment