Part of a continuing series looking at the pagan origins of the Christmas Myths,* one day at a time. Today, the story and pagan origins of the Divine Child being recognised and presented with gifts…

So the Magi arrive at the house (if you’re reading Luke’s story of the Nativity) – or the shepherds arrive at the stable (if you’re Matthew’s story of the Nativity) – or no one arrives anywhere at all (if you’re reading Mark or John’s story of the Nativity, because they didn’t see or hear or dream up of any events they considered important enough to write down) – so they arrive at this place, wherever it is and whoever they are, and they start giving gifts.

Why?

The story of the shepherds is unique in the canonical gospels to the narration in Luke, in which neither hide nor hair is seen of wise men or any other from the east.

The authors of Luke seem to have borrowed their story from The Gospel of the Egyptians, from eastern religions and myths, and from a panoply of pagan sources in which sheep, shepherds, gifts and baby feature highly.

The legends of Crishna’s birth see him cradled among shepherds, the first to hear of his wondrous birth. The shepherd Nanda recognises Crishna as the promised Saviour, and he and his companions prostrate themselves before the divine child. The Indian prophet Nared examines the stars and he too declares his divinity, and his companions present the child with gifts. These gifts are aromatic: “sandalwood and perfumes.” ( So at least Luke’s authors used some imagination in their version of the story.)

The Chinese “Son of Heaven” How-tseih was delivered unto the world in miraculous fashion was laid in a narrow lane, whereupon sheep and oxen “protected him with loving care.”

The virgin-born saviour Aesculapius enjoyed protection from goatherds, who knew instantly of his divinity and left proclaiming it far and wide.

Other legendary divinities to enjoy being either fostered or worshipped by shepherds at their birth include Dionysus (who also shares a birthday with Jesus); Romulus the co-founder of Rome; Paris, son of Priam of Troy; and the Mycenaean Aegisthus—who, like Maui, was exposed by his mother and raised by the peasants who found him.

The story told by Matthew’s authors has Magi, not shepherds (the original word here is “magoi,” from which comes our word “magician”) who visit the house in which the divine baby is laid and give him great gifts. (Sorry, no shepherds in this one. Or little drummer boys.)

The story told by Matthew’s authors has Magi, not shepherds (the original word here is “magoi,” from which comes our word “magician”) who visit the house in which the divine baby is laid and give him great gifts. (Sorry, no shepherds in this one. Or little drummer boys.)

So too does the story of the Buddha, at whose birth (right) he was visited by wise men who , by day’s end, had proclaimed him “god of gods,” and were giving him things to unwrap. Mostly “costly jewels and precious substances”—so here too, our authors have at least given some vent to their own creativity.

Rama—the seventh incarnation of Vishnu—received at his birth a visitation of “aged saints.”

When Confucius was born, “"Five celestial sages [or wise men] from a distance came to the house, celestial music was heard in the skies, and angels attended the scene."

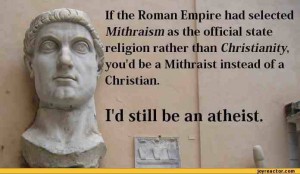

And in the stories of the birth of the Roman/Persian god Mithras, who was sent as “mediator between god and man” and whose worshippers were the Christian’s chief competition, he was visited by “wise men” called Magi at the time of his birth, and presented with … wait for it … gold, frankincense and myrrh.

And in the stories of the birth of the Roman/Persian god Mithras, who was sent as “mediator between god and man” and whose worshippers were the Christian’s chief competition, he was visited by “wise men” called Magi at the time of his birth, and presented with … wait for it … gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Well, that’s torn it then, hasn’t it. (Mithras’ birthday, by the way was also celebrated around December 25.)

But it doesn’t stop there.

According to Plato, when Socrates was born there came three Magi from the east to acclaim him. He too was, by legend, given gold, frankincense and myrrh.

And Magi also appear at the births of the Egyptian Osiris and Persian Zoroaster, as do all the now familiar elements of angels, shepherds, and gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

So rather than the Nativity being a uniquely Christian story, it seems clear enough that in formulating their own myths about their new divinity, the authors of Luke and Matthew were drawing on mythic sources going back (in the case of the oldest of these, Osiris) several thousand years.

Perhaps that is why they continue to resonate, because they have mythic if not historical truth.

All these stories have great metaphorical power, and (it’s now forgotten) were told and re-told across the great trading routes of the ancient world. That they would become associated with a new world-historical saviour figure is not surprising, says Joseph Campbell. There is, he says

a certain basic saviour mythos that is in the atmosphere of human history making. This mythos is drawn on in all such cases … It becomes attached to the personality of the saviour-hero in the way legends become attached to great figures [or those whose biographers would make great]. To take an example, consider Abraham Lincoln, who was known as a great joke teller. Within two or three decades after his death, anybody who had a good joke to tell attributed it to Abe Lincoln. So too the many anecdotes about George Washington’s honesty. [Was there ever really a cherry tree and an axe?]

They stand as a cloud of [mythic] witnesses to the greatness of the man [in the eyes of his admirers]. Their historical accuracy is unimportant.

And untrue.

READ THE WHOLE #CHRISTMAS MYTHS SERIES HERE:

- #1: Introduction, and The Miraculous Birth

- #2: The Star of Bethlehem

- #3: The Song of the Heavenly Host

- #4: The Birthplace and Surroundings of the Little Baby Jesus

Tomorrow: “The Slaughter of the Innocents”

* This and later posts in the series rely heavily on Thomas William Doane’s Bible Myths and Their Parallels in Other Religions, and Joseph Campbell’s Occidental Mythology and Thou Art That.

1 comment:

Sandalwood. Mmmm...... great fragrance (both the wood and the oil). My favourite. Expensive though.

Post a Comment