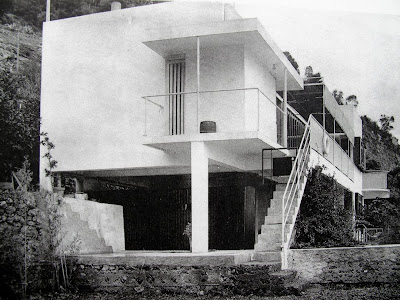

The unromantic sounding name of this concrete and steel house in the South of France disguises a romantic past, and a controversial present.

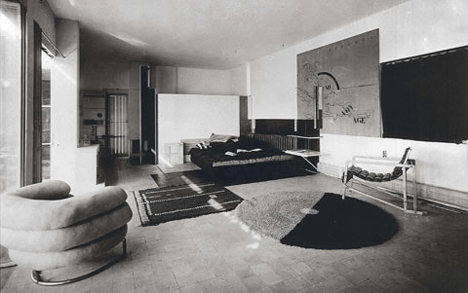

Designed with her lover Jean Badovici; painted with murals by Le Corbusier (without Gray’s permission); home to a murder in 1996; and now subject to a restoration that has been called a “massacre” of the original.

A house is not a machine to live in," wrote the pioneering modernist Eileen Gray in response to Le Corbusier's oft-quoted line about a house being a machine á habiter. "It is the shell of man—his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation."

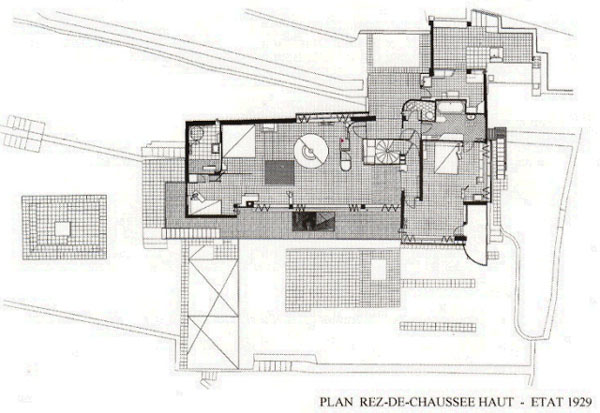

a more organic conception of a functional living space. To this end she built her house taking into consideration the angle of the sun and the wind and the elements of the site, so that in every season the house fit into its environment but also, and more importantly, provided maximum pleasure for its inhabitants.

Nothing could be further from the rationalistic Corbusian “machines for living”—ironic, really, given how over his lifetime he became obsessed with what Gray had created, even as he desecrated it.

Anglo-Irish Gray worked on E.1027's design and construction from 1926 to 1929 with her lover at the time, the Romanian-born architect and magazine editor Jean Badovici, and everything about it was premised on her love of the sea and sun, like its floor-to-ceiling windows and sunken solarium lined with iridescent tiles. An ingenious skylight staircase rose from the centre of the house like a spiralling nautilus made from glass and metal.

Sadly, the place is now known more for Corbusier’s unwelcome graffiti than for the spirit in which it was built in 1929.

[Pics from Ouno Design, WSJ, Archiseek, De Zeen, Atelier Journal]

No comments:

Post a Comment