The “housing accord” agreed to between the Auckland Council and the National Government’s Nick Smith is being talked of as a victory for National’s wish to extend the city out into green pastures over the Auckland Council’s wish to intensify existing built-up areas. (A phony dichotomy, as I’ve said before.)

Those seeing it as a defeat for the council bewail their lack of success in getting agreement on “quotas for affordable housing to be included in the accord.”

Let me here just focus on one grave misconception about what makes housing affordable, because Auckland’s planners apparently have no idea.

Little apartments, made of ticky tacky. Or “innovative techniques” used to build better shoeboxes.

But this ain’t necessarily so, and it ain’t necessarily so because it ignores the true dynamism of urban housing markets.

You see, in affordable, dynamic housing markets, most affordable housing coming onto the market is not new, smaller, cheaper housing—it’s superior-quality “second-hand” housing that is coming onto the market as a result of the vendor “moving up.”

This is important to understand, because building cheaper, smaller, shoeboxes simply means you’re building the slums of tomorrow. Whereas building newer quality housing into which people “moving up” can move into—leaving their own house available and affordable for another buyer—over time increases the overall quality of the city’s housing stock. In other words, if you want quality affordable housing, then make it possible to build larger, quality, newer housing that appears on the face if it to be unaffordable.

This seemingly contradictory point can be understood only when you learn about this concept of “churn.”

“Churn” in this context refers, as I said, to the chain of purchasers who are all “trading up” after a new house is bought and folk move into that house and out of their old one—leaving their old house empty for someone else to move into, which leaves their house empty for someone else to move into, which leaves their house empty for someone else to move into, and so on and so on right on down the line. This is “churn.”

In a healthy housing market, one house purchase by one family can start off a chain reaction of up to ten, twelve or even twenty moves further down the line as each family moves out of their old and up to their new home.

Why do I say “move up”? Because this is the housing equivalent of the weird double-thank-you moment we talk about in economics:

How many times have you paid $1 for a cup of coffee and after the clerk said, "thank you," you responded, "thank you"?

There’s a wealth of economic wisdom in the weird double thank-you moment. Why does it happen? Because you want the coffee more than the buck, and the store wants the buck more than the coffee. Both of you win.

And the proof that you win—that you both valued the exchange—is that each exchange happened voluntarily.

It doesn’t just work for coffee. Because when you decide to sell your current house to move into a new one (new to you), it’s because you want the newer place more than the old place—and your new buyer wants your old place more than their old place, and so on down the chain. You each want the new place because in your minds your new housing situation is going to be better for you than your existing housing situation.

It’s just the same for every buyer in the chain.

And the proof that you win—that you both valued the exchange—is that each exchange happened voluntarily. Increase the possibility of more exchanges like this taking place, and you increase the number of times people are able to improve their circumstances.

So every time a new house is built and purchased, of whatever value, that opens up opportunity for many other families to make their situation better.

So while the buyer of the affordable $300,000 house may not know it, but the construction of that that new $800,000 house could possibly be what just made his own life better. He’s at the end of a “chain of churn” created by that first purchaser and his vendor both saying “Thank you!”

This is what happens when the housing market is not broken by regulation, as it is now.

Which means, if the housing market were less constrained than it is now, that its entirely possible the buyer of the affordable $300,000 house has acquired his opportunity because of the construction of a new $1.8 million house!

If that idea makes your head hurt, then consider this question: is it better in general to build better houses or lesser houses? Wouldn’t we all agree that better quality is far better than lesser? So as better houses costing more are built and folk move up to what in their own view are better houses, more people are actually helped and the overall housing stock for everybody is improved.

The real answer to affordable housing then is still out there.

The answer is to fix the broken market.

And how do they do that? They stop pretending either the council’s planners or the governments know what they're doing, and they both get the hell out of the way.

* * * * *

1. For those paying attention, this is yet another example of “the seen and the unseen.” Newer “affordable” apartments mandated by quota would be seen—and seen as a direct result of the council’s quota. Cue photo opportunities all round.

Whereas the number of affordable opportunities opening up as a result of newer, more up-market housing being built, is largely unseen—and therefore mostly unavailable for politicians’ photo opportunities.

2. Yes, building costs also need to come down to make medium-cost spec building profitable again, because it’s speculative builders who until recently provided the bulk of the NZ housing stock, and who are now priced out of the medium-priced market. Until costs come down, the only place a spec builder can be sure of his margins is in the market for higher-priced housing, where prices are high enough to cover the rapidly stampeding building costs.

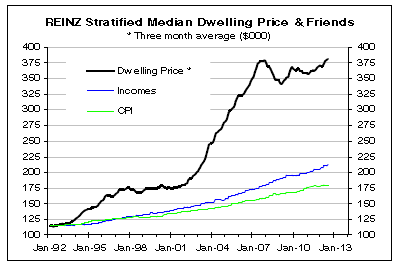

2. Of course, in a healthy market, housing prices don’t bubble up like New Zealand’s have in recent years.

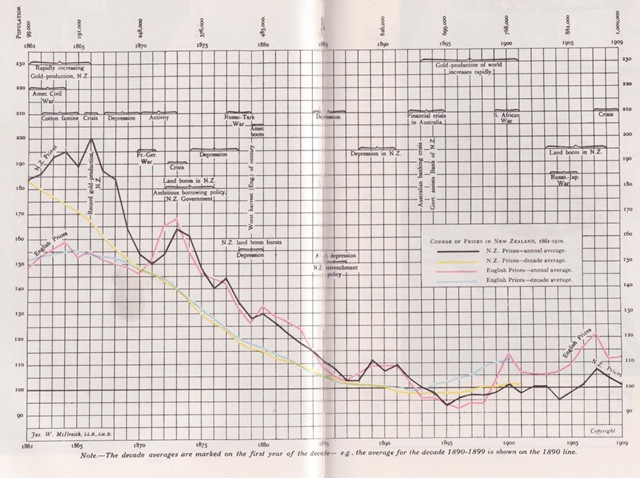

Instead, they decline gently, just as all commodities do in healthy markets enjoying stable, un-inflated currencies. Just like New Zealand & Britain were in the late 1800s…

“Course of Prices in New Zealand, 1860-1910,” from Muriel Prichard’s book ‘An Economic History of New Zealand’

“Course of Prices in New Zealand, 1860-1910,” from Muriel Prichard’s book ‘An Economic History of New Zealand’

No comments:

Post a Comment