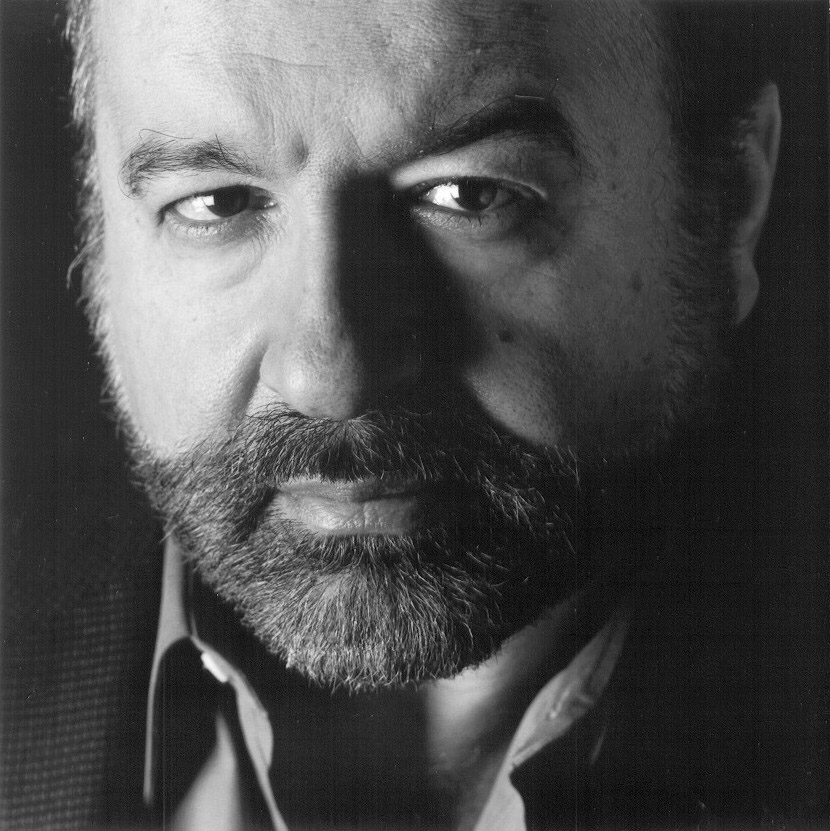

More snippets from some of my summer reading, this time from Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto’s 2003 classic The Mystery of Capital, the work that brought home to all those who read it that what the have-nots have not is at root property rights, without which they will forever remain without.

More snippets from some of my summer reading, this time from Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto’s 2003 classic The Mystery of Capital, the work that brought home to all those who read it that what the have-nots have not is at root property rights, without which they will forever remain without.

“The major stumbling block that keeps the rest of the world from benefiting from capitalism is its inability to produce capital. Capital is the force that raises the productivity of labour and creates the wealth of nations. It is the lifeblood of the capitalist system, the foundation of progress, and the one thing that the poor countries of the world cannot seem to produce for themselves, no matter how eagerly their peoples engage in all the other activities that characterize a capitalist economy.”

“Even in the poorest countries the poor save. The value of savings among the poor is, in fact, immense: forty times all the foreign aid received throughout the world since 1945. In Egypt, for instance, the wealth that the poor have accumulated is worth fifty-five times as much as the sum of all direct foreign investment ever recorded there, including the Suez Canal and the Aswan Dam.

“In Haiti, the poorest nation in Latin America, the total assets of the poor are more than 150 times greater than all the foreign investment received since the country’s independence from France in 1804. If the United States were to hike its foreign-aid budget to the level recommended by the United Nations – 0.7 per cent of national income – it would take the richest country on earth more than 150 years to transfer to the world’s poor resources equal to those that they already possess.

“But they hold these resources in defective forms: houses built on land whose ownership rights are not adequately recorded, unincorporated businesses with undefined liability, industries located where financiers and investors cannot see them. Because the rights to these possessions are not adequately documented, these assets cannot readily be turned into capital, cannot be traded outside of narrow local circles where people know and trust each other, cannot be used as collateral for a loan and cannot be used as a share against an investment. In the West, by contrast, every parcel of land, every building, every piece of equipment or store of inventories is represented in a property document that is the visible sign of a vast hidden process that connects all these assets to the rest of the economy.”“One of the greatest challenges to the human mind is to comprehend and gain access to those things we know exist but cannot see. Not everything that is real and useful is tangible and visible. Time, for example, is real, but it can only be efficiently managed when it is represented by a clock or a calendar. Throughout history, human beings have invented representational systems – writing, musical notation, double-entry bookkeeping – to grasp with the mind what human hands could never touch. In the same way the great practitioners of capitalism, from the creators of integrated title systems and corporate stock to Michael Milken, were able to reveal and extract capital where others saw just junk by devising new ways to represent the invisible potential that is locked into the assets we accumulate.”

“The proof that property is pure concept comes when a house changes hands; nothing physically changes. Looking at a house will not tell you who owns it. A house that is yours today looks exactly as it did yesterday when it was mine. It looks the same whether I own it, rent it or sell it to you. Property is not the house itself but an economic concept about the house, embodied in a legal representation. This means that a formal property representation is something separate from the asset itself.”

“For [Adam] Smith, economic specialization – the division of labour and the subsequent exchange of products in the market – was the source of increasing productivity and therefore ‘the wealth of nations’. What made this specialization and exchange possible was capital, which Smith defined as the stock of assets accumulated for productive purposes. Entrepreneurs could use their accumulated resources to support specialized enterprises until they could exchange their products for the other things they needed. The more capital was accumulated, the more specialization became possible, and the higher society’s productivity would be. Marx agreed; for him, the wealth capitalism produces presents itself as an immense pile of commodities…

“It is, as it were, a certain quantity of labour stocked and stored up to be employed, if necessary, upon some other occasion.’

… “What I take from [Smith] is that capital is not the accumulated stock of assets but the potential it holds to deploy new production. This potential is, of course, abstract. It must be processed and fixed into a tangible form before we can release it – just like the potential nuclear energy in Einstein’s brick. Without a conversion process – one that draws out and fixes the potential energy contained in the brick – there is no explosion; a brick is just a brick. Creating capital also requires a conversion process.

“This notion – that capital is first an abstract concept and must be given a fixed, tangible form to be useful – was familiar to other classical economists. Simonde de Sismondi, the nineteenth-century Swiss economist, wrote that capital was ‘a permanent value, that multiplies and does not perish . . . Now this value detaches itself from the product that creates it, it becomes a metaphysical and insubstantial quantity always in the possession of whoever produced it, for whom this value could [be fixed in] different forms.’ The great French economist Jean Baptiste Say believed that ‘capital is always immaterial by nature since it is not matter which makes capital but the value of that matter, value has nothing corporeal about it’.

“This essential meaning of capital has been lost to history. Capital is now confused with money, which is only one of the many forms in which it travels…”“As Aristotle discovered 2,300 years ago, what you can do with things increases infinitely when you focus your thinking on their potential. By learning to fix the economic potential of their assets through property records, Westerners created a fast track to explore the most productive aspects of their possessions. Formal property became the staircase to the conceptual realm where the economic meaning of things can be discovered and where capital is born.”

“The genius of the West was to have created a system that allowed people to grasp with the mind values that human eyes could never see and to manipulate things that hands could never touch.”

“Formal property is more than a system for titling, recording and mapping assets – it is an instrument of thought, representing assets in such a way that people’s minds can work on them to generate surplus value. That is why formal property must be universally accessible: to bring everyone into one social contract where they can cooperate to raise society’s productivity.”

“A good legal property system is a medium that allows us to understand each other, make connections and synthesize knowledge about our assets to enhance our productivity. It is a way to represent reality that lets us transcend the limitations of our senses. Well-crafted property representations enable us to pinpoint the economic potential of resources so as to enhance what we can do with them. They are not ‘mere paper’: they are mediating devices that give us useful knowledge about things that are not manifestly present.”

“The capacity of property to reveal the capital that is latent in the assets we accumulate is borne out of the best intellectual tradition of controlling our environment in order to prosper.”

“The philosopher John Searle has noted that by human agreement we can assign ‘a new status to some phenomenon, where that status has an accompanying function that cannot be performed solely in virtue of the intrinsic physical features of the phenomenon in question’. This seems to me very close to what legal property does: it assigns to assets, by social contract, in a conceptual universe, a status that allows them to perform functions that generate capital.”

“Throughout history people have confused the efficiency of the representational tools they have inherited to create surplus value with the inherent values of their culture. They forget that often what gives an edge to a particular group of people is the innovative use they make of a representational system developed by another culture. For example, Northerners had to copy the legal institutions of ancient Rome to organize themselves, and learn the Greek alphabet and Arabic number symbols and systems to convey information and calculate. And so, today, few are aware of the tremendous edge that formal property systems have given Western societies. As a result, many Westerners have been led to believe that what underpins their successful capitalism is the work ethic they have inherited, or the existential anguish created by their religions – in spite of the fact that people all over the world all work hard when they can, and that existential angst or overbearing mothers are not Calvinist or Jewish monopolies… Therefore, a great part of the research agenda needed to explain why capitalism fails outside the West remains mired in a mass of unexamined and largely untestable assumptions labelled ‘culture’, whose main effect is to allow too many of those who live in the privileged enclaves of this world to enjoy feeling superior…

“This is not to say that culture does not count. All people in the world have specific preferences, skills and patterns of behaviour that can be regarded as cultural. The challenge is fathoming which of these traits are really the ingrained, unchangeable identity of a people and which are determined by economic and legal constraints. Is illegal squatting on real estate in Egypt and Peru the result of ancient, ineradicable nomadic traditions among the Arabs and the Quechuas’ back-and-forth custom of cultivating crops at different vertical levels of the Andes? Or does it happen because in both Egypt and Peru it takes more than fifteen years to obtain legal property rights to desert land? In my experience squatting is mainly due to the latter. When people have access to an orderly mechanism to settle land that reflects the social contract, they will take the legal route and only a minority, like anywhere else, will insist on extra-legal appropriation. Much behaviour that is today attributed to cultural heritage is not the inevitable result of people’s ethnic or idiosyncratic traits but of their rational evaluation of the relative costs and benefits of entering the legal property system.

“Legal property empowers individuals in any culture, and I doubt that property per se directly contradicts any major culture. Vietnamese, Cuban and Indian migrants have clearly had few problems adapting to US property law. If correctly conceived, property law can reach beyond cultures to increase trust between them and, at the same time, reduce the costs of bringing things and thoughts together. Legal property sets the exchange rates between different cultures and thus gives them a bedrock of economic commonalities from which to do business with each other.”“And so formal property is this extraordinary thing, much bigger than simple ownership. Unlike tigers and wolves, who bare their teeth to protect their territory, man, physically a much weaker animal, has used his mind to create a legal environment – property – to protect his territory. Without anyone fully realizing it, the representational systems the West created to settle territorial claims took on lives of their own, providing the knowledge base and rules necessary to fix and realize capital.”

No comments:

Post a Comment