THE SINGLE MOST IMPORTANT HISTORICAL event of the last fifty years was the collapse of Communism, and with it the liberation of hundreds of millions from slavery.

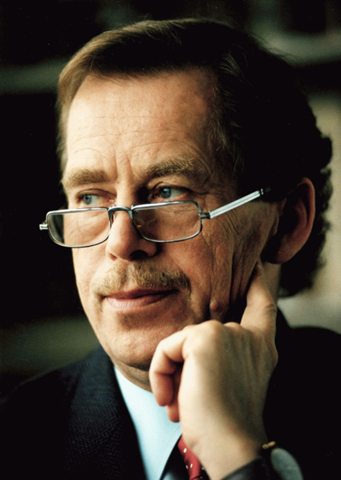

One of the most important figureheads in that fall died last night: Vaclav Havel, dissident playwright, Velvet Revolutionary, the first president of the free Czechoslovakia he and his colleagues wrested from the Soviets, and the man who successfully guided the Czech Republic from communism to relative freedom.

His story is as inspiring as his understanding that authoritarianism can never last; that the collapse was inevitable; that authoritarian rule is inevitably the victim of a "lethal principle" that will always destroy it:

"Life cannot be destroyed for good," he wrote in a widely-circulated samizdat letter in the last years of Soviet rule. “A secret streamlet trickles on beneath the heavy crust of inertia and pseudo-events, slowly and inconspicuously undermining it. It may be a long process, but one day it has to happen: the crust can no longer hold and starts to crack. This is the moment when something once more begins visibly to happen, something new and unique."

HAVEL—PLAYWRIGHT, POET, MAGAZINE editor and a dissident against totalitarian rule since the mid-sixties—led the 1989 ‘Velvet Revolution’ which overturned the Communist government of Czechoslovakia, and remained as President of the new country until he retired.

The Velvet Revolution was a revolution of ideas - ideas that in the end saw the Communists concede rather than confront them; Havel won with his principles, which he developed in his many battles to beat the Bolshevik bastards back. He and his supporters were regarded as a major threat by the communists not because of their numbers, but because of what they said. More particularly, the communist government knew that when Havel said something, HE MEANT IT.

Vaclav Havel had no intention of ending up in his country’s presidential palace; it was his fight to keep his own magazine, Tvar, alive and un-banned that got him involved in politics, but the way he fought eventually brought down a government. His fight was based on ideas, it was based on principle, and it required an almost ineffable patience.

Havel learnt a crucial lesson in the power of principle very early in his career. He learned to never rely on the “moderates”—that it is these creatures who are your biggest enemies; it is them who will knife you in the back while smiling. He learned this when he was sold out by his own fellow writers and imprisoned; sold out by souls so cowardly, so in thrall to the Soviets - so craven - that they would rather die on their knees than even give thought to the notion of standing up for their own freedom. Havel and his supporters learnt then that if they were ever to achieve anything they must stand up for themselves. They did, and eventually they won their country.

Two years before the ‘Velvet Revolution’ there were no outward signs that his years of struggle would ever have any tangible effect, yet Havel remained adamant that the struggle was worth it; he was convinced that totalitarianism contained within it a ‘lethal principle’ which would eventually kill it. He described this principle in a illicit ‘samizdat’ essay widely-circulated in the desolate years after the Soviets had crushed the Prague Spring

[Havel] described a society governed by fear - not the cold, pit-of-the-stomach terror that Stalin had once spread throughout his empire, but a dull, existential fear that seeped into every crack and crevice of daily life and made one think twice about everything one said and did.

The essay was, in fact, a state of the union message, and it contained an unforgettable metaphor: the regime, the author said, was "entropic," a force that was gradually reducing the vital energy, diversity, and unpredictability of Czechoslovak society to a state of dull, inert uniformity. And the letter also contained a remarkable prediction: that sooner or later, this regime would become the victim of its own "lethal principle." "Life cannot be destroyed for good," [Havel] wrote. “A secret streamlet trickles on beneath the heavy crust of inertia and pseudo-events, slowly and inconspicuously undermining it. It may be a long process, but one day it has to happen: the crust can no longer hold and starts to crack. This is the moment when something once more begins visibly to happen, something new and unique." *

"Life cannot be destroyed for good." Fifteen years after Havel wrote those words in a samizdat pamphlet those streamlets burst forth, sweeping away communist regimes from Berlin to Bucharest and carrying the playwright Vaclav Havel from the ghetto of dissent to the world stage. Those extraordinary events of 1990 enrich that letter with new levels of meaning.

HAVEL FIRST BECAME INVOLVED in political resistance in the mid-sixties in his efforts simply to survive; to keep alive his small literary magazine, Tvar, in the face of pressure from the Communist Party to close it down. In resisting, he discovered what he called "a new model of behaviour":

When arguing with a center of power, don't get sidetracked into vague [nitpicking] debates about who is right or wrong; fight for specific, concrete things, and be prepared to stick to your guns to the end.

That model of principled behaviour served him well:

On Tuesday morning, November 28,1989, Havel led a delegation of the Civic Forum to negotiate with the Communist- dominated government. The issue was not a magazine this time, it was the country. Ten days before that, the "Velvet Revolution" had been set in motion by a student demonstration in Prague; that was followed by a week of massive demonstrations culminating. in a general strike on Monday, November 27. Early Tuesday afternoon, following the meeting, the government announced that it had agreed to write the leading role of the Communist Party out of the constitution. We do not know what was said at the meeting, but I don't think we would be far wrong to assume that the discussion stayed very close to the concrete issue of amending the constitution, and that the Civic Forum delegation stuck to their guns. A principle that Havel and his colleagues had learned decades before now stood them in good stead.

By the end of that month, Havel was President of the country in a process that readers of Atlas Shrugged could easily recognise. The battle begun simply to save Havel’s magazine had ended by saving the people of Czechoslovakia.

Yet he recounts how he began this battle simply by resisting pressure from his local 'Writers Union' to 'persuade' him to close the magazine. He quickly realised that his real enemies were not the Soviets. His real enemies were all those who Lenin had once called his ‘useful idiots’ – all those like the Writers' Union who are prepared to compromise with their enemies and to sell out their friends - supposed allies who, in accepting servitude for themselves, happily impose it on others.

In the end though and despite his resistance, [the banning of Tvar] became more and more inevitable. The Central Committee of the Union had to make it appear as though they were doing it on their own initiative, but in fact they were ordered to do it by the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Left to themselves, the anti-dogmatics [as the wowsers were descriptively called] would not have banned us, but we weren't worth a rebellion inside the party so they did it anyway. Of course they explained it to us in their traditional 'anti-dogmatic' way: The struggle for great things - the general liberalization of conditions - demands minor compromises in things that are less important . It would not be tactical to risk an open conflict over Tvar, because there is bigger game at stake [etc., etc]. … This is [the very] model of self-destructive politics. …

We argued that the best way to liberalize conditions is to be uncompromising precisely in those "minor" and "unimportant details, such as the publication of this or that book or this or that little magazine. Our argument was not heard. Nevertheless, a kind of hangover from this experience remained in anti-dogmatic circles. And it began to spread rapidly when we refused to accept their ultimatum silently, and refused to accept the rules of the game as they had played it until then.

Havel and his Tvar team mobilised to defend themselves, organising petitions and meetings amongst their fellow writers, refusing - in Ayn Rand's words - to accept the sanction of the victim. Used to more compliant behaviour from their victims, this unusually principled resistance got under the skin of the Central Committee:

I think our efforts had a great importance, one that has not been recognized, even today. We introduced a new model of behaviour: don't get involved in diffuse … polemics with the centre, to whom numerous concrete causes are always being sacrificed; fight "only" for those concrete causes, and be prepared to fight for them unswervingly, to the end. In other words, don't get mixed up in back-room wheeling and dealing, but play an open game.

I think in this sense we taught our anti-dogmatic colleagues a rather important lesson; … They realized that many of their former methods were hopelessly out of date, that a new and fresher wind was blowing, that there were people - and there would obviously be more and more of them - who would not be stopped in their tracks by the argument that a concrete evil was necessary in the name of an abstract good. In short, I think that Tvar had an educational effect on the anti-dogmatic members of the writing community. Suddenly here was the party taking us, a handful of fellows, more seriously than the entire anti-dogmatic "front." And they were taking us more seriously for the simple reason that we could not be so easily talked out of our convictions.

In 1969, Havel wrote to Alexander Dubcek, the face of the brief 'Prague Spring' before it was crushed by the Soviets, pleading with him to leave political life rather than let himself be used as a propaganda pawn. Dubcek did leave office. Reflecting on that letter seventeen years later, Havel wrote:

I had written that even a purely moral act that has no hope of any immediate and visible political effect can gradually and indirectly, over time, gain in political significance. In this I found, to my own surprise, the very same idea that, having been discovered by many people at the same time, stood behind the birth of Charter 77 and which to this day I am trying - in relation to the Charter and our "dissident activities" - to develop and explain and, in various ways, make more precise.

In an interview two years before the Soviets fell, when from the outside things still seemed apparently hopeless, Havel reflected that years of seemingly hopeless resistance had indeed produced effects, though not ones that everyone would notice :

[Our various actions], of course, have wider consequences. Today far more is possible. Think of this: hundreds of people today are doing things that not a single one of them would have dared to do at the beginning of the seventies. We are now living in a truly new and different situation. This is not because the government has become more tolerant; it has simply had to get used o the new situation. It has had to yield to continuing pressure from below, which means pressure from all those apparently suicidal or exhibitionistic civic acts. People who are used to seeing society only 'from above" tend to be impatient. They want to see immediate results. Anything that does not produce immediate results seems foolish. They don't have a lot of sympathy for acts which can only be [practically] evaluated years after they take place, which are motivated by moral factors, and which therefore run the risk of never accomplishing anything. …

Unfortunately, we live in conditions where improvement is often achieved [only] by actions that risk remaining forever in the memory of humanity [as] an exhibitionistic act of desperate people.

Havel, reflects that it is the sum total of these many 'hopeless acts' of 'exhibitionism' that in the end force change; that only by not lying down in the face of an apparently hopeless struggle are these crucial and very tangible victories achieved:

To many outside observers [the many small victories of principled action] may seem insignificant. Where are your ten-million strong trade unions? they may ask. Where are your members of parliament? Why does [the President] not negotiate with you? Why is the government not considering your proposals and acting on them? But for someone from here who is not completely indifferent, these [small signs] are far from insignificant changes; they are the main promise of the future, since he has long ago learned not to expect it from anywhere else.

I can't resist concluding with a question of my own. Isn't the reward of all those small but hopeful signs of movement this deep, inner hope that is not dependent on prognoses, and which was the primordial point of departure in this unequal struggle? Would so many of those small hopes have "come out" if there had not been this great hope "within," this hope without which it is impossible to live in dignity and meaning, much less find the will for the "hopeless enterprise" which stands at the beginning of most good things.

Freedom lovers everywhere might reflect on Havel’s words, and his experience. We must sometimes seem to be such an apparently "hopeless enterprise" as he describes, engaged in a doomed an unequal struggle.

But we can learn from Havel that such an apparently "hopeless enterprise" can eventually ignite success. As he suggests, if our own actions are to ever become "the beginning of … good things" we must always let our hope "within" motivate us to action.

We must realise we ourselves are the change we hope to make in the world; that our ostensive enemies are really only paper tigers supported by nothing but lies; that our real enemies are the inertia of thousands with heads full of mush, and our so-called friends with nothing in their souls but marshmallow.

Havel himself had to spend four years in jail before his battle was won. Little wonder. Power does not concede without a struggle. As former American slave Frederick Douglass said, struggling for freedom in the century before Havel’s: " The struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle! "

The struggle for freedom goes on, its path lit by heroes like Douglass and Havel.

We mourn the loss of Vaclav Havel, and celebrate his life.

* * * *

* Quotes are from the book Disturbing the Peace.

8 comments:

Great man.

Great post, Peter.

Thanks for the informative post, PC. Interesting that Vaclav Havel was a member of the Czech version of the Green Party. Vaclav Klaus, who was prime minister under Havel, and then succeeded Havel as President of the Czech Republic, was one of his (Havel's) political opponents.

Well written post , Peter

Thank you for honouring a hero.

Couldn't help but note whilst reading your excellent article that the removal of the NZ on Air tax was rather hollow, in that the message entailed didn't catch on. {But the $1000 fine was not a deterrent to retaining libertarian ideals}

Peter

Lenin had once called his ‘useful idiots’

This was a phrase used by American anti-communists. Lenin never said it.

Great post Peter.

Thanks Peter

Are you aware that Vaclav Havel was a member of the Club of Rome?

Vaclav Klaus has nothing good to say about it.

To know more about this pernicious organisation go here:

http://recyclewashington.wordpress.com/2010/04/29/unraveling-the-club-of-rome-part-1/

Post a Comment