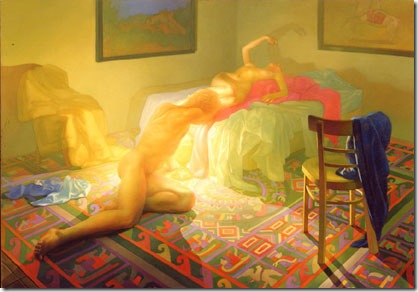

I’ve enjoyed reading the debate over this painting below that I posted here last week, and I’ve been very careful (though tempted) to wade in myself.

I haven’t, but I will now.

The painting was done by the Soviets’ leading figurative painter, showing Russian fighters defending the Soviet city of Sebastopol from Nazi invaders. The question I posed when posting it was: does heroic art like this supersede the politics it celebrates? In other words, is good art didactic, or something else?

While you’re considering that yourself, add this sculpture to your mix if you like, a piece of Soviet agit-prop called ‘A Cobblestone Is the Weapon of the Proletariat,’ which got no comment at all when I first posted it:

Or this piece of music (part one of three). It was said to be Hitler’s most-loved piece—by the composer most-played by the Nazis—and played over German radio the day of his death.

So does painting, sculpture and music such as this supersede the politics it celebrates (or in the latter case was used to celebrate)? Simon contends it can’t, especially (as he contends with the painting above) if the art was done by a slave to celebrate a slave state. He says, “Generally some knowledge of the subject matter is helpful in that you might understand the art better.” That’s true, it’s helpful – especially if there’s some obscure symbolism or something going on. But I agree with other commenters in saying with good art that while it’s helpful to know more, it’s certainly not essential.

Because a piece of art stands on its own. What we see with that sculpture above, for example, is primarily the theme of determined resistance. The young man’s brows are furrowed, his eyes focussed on his goal, his whole (slightly lumpen) being coiled into one super-human action. He could just as easily be resisting Czarist cossacks, Soviet tanks, British redcoats or Iranian militia – the key qua art is that he is resisting. And not without hope. In essence, the piece says that goal-directed resistance has power in our universe.

That’s a theme that transcends ideology, and even politics. (Compare it with the look in the eyes and face of the Michelangelo and Bernini Davids, however, two other examples that could be used here, to see a very different conception of where human goal-direction starts. Do you see it?)

Anyway, that in a nutshell is why good art transcends its politics—and why so much purely “didactic art” is so bad; why so much so-called didactic “art” is generally more the former than it is the latter. As Ayn Rand concludes:

Art is not the means to any didactic end. This is the difference between a work of art and a morality play or a propaganda poster. The greater a work of art, the more profoundly universal its theme. Art is not the means of literal transcription. This is the difference between a work of art and a news story or a photograph.”

A piece of art stands on its own. If it’s good art that expresses its theme superlatively (which is the job of every artist, no matter his theme) then it says to the observant viewer that this is what the artist sees as essential in the universe, as fundamentally “metaphysically” important—and it’s on that basis that you respond. Either with a “values swoon” (if you agree), or with loathing (if you don’t).

In this context, Painter Michael Newberry argues that the important point in understanding a painting, for example, is to grasp that “the canvas is the universe”:

In art criticism one should analyze the artwork without outside considerations. This means that the theme of a painting, for instance, should make its message clear without any prior knowledge of what the painting is about. We have to be like detectives and look for clues within the painting itself.”

For help in seeing what he means, and in detecting value judgements in paintings without any prior knowledge of the subject itself, you can’t go past Michael’s own excellent piece ‘Detecting Value Judgments in Painting,’ which is chock full of examples, and itself stands on its own as the best practical description of the skill that I’ve seen.

6 comments:

Without thinking too much, I do think of Berthold Brecht, who, from his theorising was trying to use the power of the art to make his point, at the same time finding it was necessary to subvert (what might at least traditionally be considered) the quality of it to do so.

It's been said that in the end he was too good a dramatist to play his theories out properly; the logical end is agit-prop street theatre and we all know that's not about the art.

Word verf: capon. Bourgoise chicken.

I must first admit that I am a little (a lot) out of my depth, or comfort zone here, but my impression or the effect the painting and the sculpture give me are not political.

The sculpture could be of any oppressed or enslaved, nationality fighting for his life and striving to complete a task which if he didn't, would put his life at risk (for whatever reason)

The painting is the goodies versus the baddies - The black guys versus the white guys.

It is a non defined) people defending something that is theirs from (non defined) people who would take it by force.

It is a fight for survival.

Is this what you are asking?

I shall now go to the dictionary to find out what the f#*! "didactic" means! :-)

My God, tat Michael Newberry painting is powerful....

sorry... 'that'

OK generally prefer Eric Hoffer to Ayn Ryan. Hoffer on art / creativity says that:

“In products of the human mind, simplicity marks the end of a process of refining, while complexity marks a primitive stage. Michelangelo’s definition of art as the purgation of superfluities suggests that the creative effort consists largely in the elimination of that which complicates and confuses a pattern.”

Hoffer’s view supports the idea that the art should stand on its own with an understandable theme and it seems knowledge is not essential for the art to work.

Furthermore yes that art should show what the artists consider essential in the universe or what they consider essential human values. Basic human values override any politics or ideology. In this case the theme “goal-directed resistance has power in our universe” certainly transcends anything Marx or Lenin promoted or forced.

Yes this works in a free society.

Having understood that (I think) art is still subjective and the exchange between the artist and viewer is a private one. The artist can only expect everyone to have a different view of their art. (not necessarily love or hate as a reaction to the artist’s value system or any reaction for that matter)

Everyone has their particular opinion in part because they do have some knowledge of the subject matter. This is unavoidable.

For to art to work I would have thought it important for people to have the ability to say what they think. The freedom to actually analyze the painting in the way the links suggest and then reject or accept.

In the Soviet Union while yes goal-directed resistance has power in our universe rises above Leninism but the political structure takes away your ability to express this opinion. The talent and skill and all that is good about art is nullified by the political regime.

Post a Comment