In the nineteenth century the Statue of Liberty, called officially 'Liberty Enlightening the World,' was gifted by France to the people of New York as a sign of their common friendship in liberty. It was a gift to the Nation of the Enlightenment from a country who played a major part in the Age of Enlightenment, and as a symbol of liberty it is still preeminent.

In the nineteenth century the Statue of Liberty, called officially 'Liberty Enlightening the World,' was gifted by France to the people of New York as a sign of their common friendship in liberty. It was a gift to the Nation of the Enlightenment from a country who played a major part in the Age of Enlightenment, and as a symbol of liberty it is still preeminent.

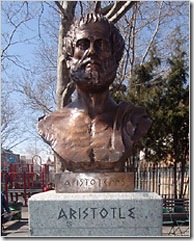

Another gift to the American people has just been unveiled in a New York park, a gift from Greece to the American people -- a bust of the 'Father of the Enlightenment' given to the Nation of the Enlightenment by the country that gave him birth. Story here in the New York Times.

Another gift to the American people has just been unveiled in a New York park, a gift from Greece to the American people -- a bust of the 'Father of the Enlightenment' given to the Nation of the Enlightenment by the country that gave him birth. Story here in the New York Times.

Of course, that's not exactly the way the gift citation reads, but as the city’s parks commissioner said at the bust's unveiling: “In the spirit of Aristotle’s words, ‘The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance'."

NB: Further on the 'Aristotle is the Father of the Enlightenment' theme is this, ahem, enlightening passage from Leonard Peikoff:

The development from Aquinas through Locke and Newton represents more than four hundred years of stumbling, tortuous, prodigious effort to secularize the Western mind, i.e., to liberate man from the medieval shackles. It was the buildup toward a climax: the eighteenth century, the Age of Enlightenment. For the first time in modern history, an authentic respect for reason became the mark of an entire culture; the trend that had been implicit in the centuries-long crusade of a handful of innovators now swept the West explicitly, reaching and inspiring educated men in every field. Reason, for so long the wave of the future, had become the animating force of the present... The father of this new world was a single philosopher: Aristotle. On countless issues, Aristotle's views differ from those of the Enlightenment. But, in terms of broad fundamentals, the philosophy of Aristotle is the philosophy of the Enlightenment.

4 comments:

Aristotle was in fact the Philosophical father of medieval scholasticism. The enlightenment was in many was a rejection of Aristotelianism. In fact the scientific revolution in many was came about due to theological rejections of Aristotle in the late middle ages.

And to see Aquinas, Locke and Newton as “secularisers” of the western mind is mistaken. Aquinas was a Catholic Theologian who was attempting to develop an overtly Christian Philosophy he was part of the newly founded domican order set up to combat heresy in europe. Locke was a Protestant who wanted to use reason to vindicate the Christian religion and morality; he also wanted to exclude Catholics from the throne and supported the suppression of atheists.

Newton was a Christian Theist, whose physics was based on late medieval rejection of Aristotle in favor of the voluntarism nominalist had been promoted b Christians like Ockham and Scotus. Newton believed that because God had created the world freely, the world was contingent and governed by contingent laws, because of this one could discover these laws by empirical research not by a prori metaphysics as the Aristotelians had maintained.

But why let the facts get in the way of Randian propaganda

Matt,

Your years spent studying theology and religious apologetics will certainly have given you more acquaintance with propaganda than facts -- the Church's two-thousand years in the propaganda business being the world's longest at the job -- so it's unsurprising that you see propaganda instead of facts, and unsurprising that you're peddling the Church's propaganda here to defend it.

Readers will no doubt be aware that the Church has had some two-thousand years to prepare its propaganda in defending the indefensible, so it will be admitted that some facility to do so should be evident.

However, the whole truth of the matter is at odds with the Church's propaganda, in which the religionists' facility with cherrypicking is on display in your every word.

The fact is that since the rediscovery of Aristotle's writings, the Church has sought to reconcile reason and mysticism, and to appropriate the pagan Aristotle as some sort of patron saint.

But reason and mysticism can't be reconciled, and neither can Aristotle and religion, which is why the Church had to resort to sophism, apologetics and propaganda.

You see, at the root of the Enlightenment was the knowledge that reason is capable of explaining existence -- that is, that reason is our means of acquiring knowledge, and it is knowledge of this world, not of the next one. Knowledge of nature, not of “super-nature,” is what promotes life on earth, and it is this that makes Aristotle the Father of the Enlightenment in every important respect, since in every important respect it is his philosophical commitment to reason and to this earth that is expressed in Newtonian physics, in Locke's politics, in Adam Smith's economics ... indeed, in the whole Enlightenment project.

In every important respect this represents a complete overturning of mysticism, which is to say the 'thinking' (or lack thereof) of the Dark Ages.

Aristotle's method of observation-based rationality was so utterly at odds with the religionist thinking that had dominated the Dark Ages, and was responsible for those Ages being Dark, that they struck even religious thinkers like a bombshell when they were rediscovered after a millennia of darkness. That Aristotle was "the Philosophical father of medieval scholasticism" is not in fact to suggest that Aristotle would have recognised what the medieval scholastics were up to -- which, bluntly, was trying to reconcile the Aristotelian bombshell' with the Church's supernatural nonsense. That is, to reconcile reason and mysticism.

It can't be done, of course, which explains the sophism of so much medieval scholasticism. The result is a mongrel in which one of the two sides eventually dominates. That reason eventually triumphed (at least did so in the west) is why the west eventually escaped the Dark Ages in which religion had put it. The small opening for reason that Thomas Aquinas created when he allowed a role for reason was eventually to expand into the role for reason that was to trimuph in the Enlightenment, which was to "fix reason firmly in her seat" as a means by which to live on this earth.

Instead of seeing this world as a vale of tears and darkness which we endure until God chooses to take us, reason, the Enlightenment and Aristotle all see this earth as something to understand, and a place in which we can flourish.

Such thinking came as a revelation to every western European thinker when they were rediscovered by the West.

As Andrew Bernstein explains, "It is widely recognized that knowledge of nature, not of “super-nature,” promotes life on earth. Therefore, when the works of Aristotle—the master of natural science and secular philosophy—were rediscovered in 12th-century Islamic Spain, it is no mystery that Western European thinkers—after centuries of suppression and penury—turned to him with the desperate hope that his wisdom could relieve their earthly sufferings. And, as the history of the West since that time attests, not only was suffering relieved; life proper to man was made possible.

******************

You say, "Aristotle was in fact the Philosophical father of medieval scholasticism."

Yes, he was, but not in the way you suggest. Aristotle's writings were rediscovered by the west after a millennia of darkness brought on by theology.

To say it again, what was rediscovered with Aristotle was the power of reason to understand this earth.

As the author of 'The Aristotle Adventure' "Burgess Laughlin summarises: "In sum, Western Europeans rediscovered Aristotle’s writings when they were desperately eager for the wisdom and cognitive method those works contained. It is no exaggeration to claim that when Aristotle’s method of observation-based rationality, in concert with innumerable specific theories and insights, was culturally prevalent, great advances followed; when absent or suppressed, there ensued only ages miserably dark."

****************

You say, "the scientific revolution in many was came about due to theological rejections of Aristotle in the late middle ages."

In fact the the scientific revolution came about because of a rejection of the Church's intellectual domination. Need I mention Galileo? That Galileo saw Aristotle as an adversary was wholly due to the Church's appropriation of The Philsopher, but in evey important respect Galileo's method of observation-based rationality was Aristotle's, whether Galileo knew it or not.

*****************

The rest of your arguments reflect an equal amount of cherrypicking of the facts:

Newton is not revered for his mystic rambklings or his alchemy; he is revered because his physics integrated and explained such a wealth of actual observations of reality.

Locke is revered not for wanting to exclude Catholics from the throne and supporting the suppression of atheists, but for explaining that the protection of individual rights is the only legitimate job of governments, and explaining and integrating the method by which individual rights are best protected.

Aquinas is revered not because he was part of the newly founded the Domican Order set up to combat heresy in Europe, but because he opened the door to intellectual freedom in the west, however inadvertently.

Ockham and Scotus and Albertus Magnus are properly revered not because they were Christians, but for their enormous contributions to the popularisation of logic and reason in an age of Christian darkness.

If a Victor Hugo had been around to see Ockham and Scotus and Albertus Magnus and Quinas promoting and using reason, however fumblingly, within the superstructure of the religious mania still at large around them, he would have been heard to comment, "This will kill that," because to the extent that reason is respected, then kill religion reason assuredly will.

****************

In conclusion, if readers wish to see an utter demolition of the religionist propaganda that's been propagated for centuries (and which Matt is peddling here), then I can wholeheartedly endorse Andrew Bernstein's demolition of Rodney Stark's book-length thesis that "Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success."

Read the demolition here: The Tragedy of Theology: How Religion Caused and Extended the Dark Ages by Andrew Bernstein.

PC

Well done. That's as concise an exposition of the facts as can be read on this topic. Nevertheless, you can expect to be lectured aand bullshitted to at length by believers and sophists who just will never accept that their opinions are false; a tissue of fibs. Seriously, you can't reason with these creatures. They are exactly the same as communists in that regard (similar ideals, similar approach to debate, similar lack of intellectual honesty or ability, similar wasters of time and resources).

There was an excellent quote that goes along the lines of: religion is for people looking for an intellectual shortcut, but what they obtain is a mental short-circuit.

LGM

I am sorry PC but denigrating anothers qualifications, calling positions you disagree with names (like propaganda and cherry picking) does not actually provide any adequate rebuttal. Nor does repeatedly asserting the position you hold to and pointing out that some libertarians agree with you.

Seeing you made a length response allow me to address your errors in turn

1. You see, at the root of the Enlightenment was the knowledge that reason is capable of explaining existence -- that is, that reason is our means of acquiring knowledge, and it is knowledge of this world, not of the next one. Knowledge of nature, not of “super-nature,” is what promotes life on earth,

Actually, No, many of the major enlightenment figures did not limit reason to nature. Descartes’ defended the ontological argument. Locke, defended Christianity and theism and in fact his epistemology was motivated by the desire to be able to come to correct conclusions about God (this is according to what his friend wrote on one of the earliest manuscripts of Locke’s essay). Berkley was a theist who wanted to refute materialism. Hume’s religious affinities are a matter of debate. Reid was a Presbyterian minister who wanted to use reason to fight skepticism about religion. Berkley defended the ontological and cosmological arguments and used reason to develop a theodicy. Kant wanted to make room for faith and immortality and defended the moral argument. Newton’s preface states that his basis for adopting the scientific method was theological (and anti Aristotelian btw) and he developed his physics so as to defend the existence of God.

I could go on.

Moreover, one of the major problems with the epistemology of the enlightenment (known as classical foundationalism) is that it had trouble providing a basis for knowledge of an external world. This is a central issue in Descartes’ through to Locke, Berkley, Hume, Reid, etc. Locke believed that much of what we perceive are secondary qualities and created by our mind Hume took the skepticism to its conclusion. Berkley, Reid and Descartes appealed to theology to solve these skeptical problems. Kant used this skepticism to defend theology. (btw. I learnt this not studying Philosophy at Waikato but studying and latter teaching the history of at Otago)

2. The fact is that since the rediscovery of Aristotle's writings, the Church has sought to reconcile reason and mysticism, and to appropriate the pagan Aristotle as some sort of patron saint.

Actually the project of using reason to defend develop and refine faith predates Aristotle and goes all the way back to Philo of Alexandria. Early Church fathers like Justin ( a Greek philosopher) Origen, Athanasius, Augustine, Athenagoras, Clement, Gregory of Nazianius, Basil, to name a few. Moreover classical Greek philosophy and learning was promoted prior to Aquinas by people like Boethius, Isidore, Anselm, Bede, Peter Damian, Abelard. And so on. Some early Christian thinkers were hostile to Greek Philosophy or hostile to it in certain contexts but many were not and the suggestion that the anti-philosophy camp was main-stream is simply false.

3 Aristotle's method of observation-based rationality was so utterly at odds with the religionist thinking that had dominated the Dark Ages, and was responsible for those Ages being Dark, that they struck even religious thinkers like a bombshell when they were rediscovered after a millennia of darkness.

Wrong again, Numbers and Lindberg note that recent historical research suggests that this portrayal of the early middle ages as “the dark ages” is a caricature.(David C Lindberg “The Medieval Church Encounters the Classical Tradition: Saint Augustine, Roger Bacon and the Handmaiden Metaphor” in When Science & Christianity Meet, ed. David C. Lindberg & Ronald L. Numbers (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2003), 7-8. )A conclusion shared by the studies of Henri Pirenne ( A History of Europe from the End of the Roman World in the West to the Beginning of Western States, (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1958)) and Marc Bloch (Marc Bloch, ( Feudal Society, (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1961)) and Richard Hodge (“The Not So Dark Ages”, Archaeology 51 (September/October 1998)

The 1975 New Columbia Encyclopaedia states that the term “Dark ages” is no longer used by historians because this period is “no longer thought to have been so dim’ similarly the Encyclopaedia Britannica states the term “Dark ages” is “now rarely used by historians because of the unacceptable value judgment it implies” the term “dark ages” incorrectly implies this was “a period of intellectual darkness and barbarity” In fact the article you link to admits this point it states that in “recent decades, medieval scholars have persistently advanced the thesis that the Dark and Middle Ages were not actually dark—that the 1,000-year period stretching from the fall of Rome (roughly 500 AD) to the Renaissance (roughly 1500) was an era of significant intellectual and cultural advance.”

3 “when the works of Aristotle—the master of natural science and secular philosophy—were rediscovered in 12th-century Islamic Spain, it is no mystery that Western European thinkers—after centuries of suppression and penury”

Actually the suppression of heretic views did not occur in the so called dark ages. The early church supported freedom of religion until the fifth century when Augustine reluctantly supported suppression of the dontatists. Some roman emperors put in place laws against heresy which were enforced sporadically in the late roman period (often with protests from the church) but these laws fell out of use and were not enforced in the period mistakenly called the Dark ages. It was not until the late middle ages that heresy was suppressed by Inquisitional courts. In fact it was the heavily Aristotelian Dominican order which carried this suppression out and which justified it. This is all well documented in Joseph Lecler Toleration and the Reformation, trans. by TL Weslow (New York: Association Press, 1960), Edward Peter’s, Inquisition, (London: Collier Macmillan, 1981) And also by Stark (For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts, and the End of Slavery (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004) [ I note that in the article you link to Berstein chides Stark for not mentioning the suppression of heretics in his work, ignoring the fact that Stark has written a whole book on the topic]

4. In fact the the scientific revolution came about because of a rejection of the Church's intellectual domination.

The thesis that the Church for centuries consistently suppressed science and prevented its flourishing (known as the conflict thesis) originates in two works John Draper’s History of the Conflict between Religion and Science (1874) and Andrew Dickson White in his book A History of The Warfare Between Science and Theology in Christendom. The conflict thesis is now widely rejected by historians of science. Several people such as Stanley Jaki, (The Road to Science and the ways to God (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978)) Alfred Whitehead, (Science and the Modern World (New York: Macmillan, 1925) Peire Duhem, (L'Aube du savoir: épitomé du système du monde (histoire des doctrines cosmologiques de Platon à Copernic), ed. Anastasios Brenner, Paris, Hermann. Selections from Duhem 1913-59.)) Michael Foster ("The Christian Doctrine of Creation and the rise of Modern Natural Science", Mind 43 (1934), 446–468 "Christian Theology and Modern Science of Nature (I)" Mind 44 (1935), 439–466. "Christian Theology and Modern Science of Nature (II)" Mind 45 (October, 1936), 1–27.) and Reijer Hookykaas (Religion and the Rise of Modern Science (Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdmans, 1972), Reijer Hookykaas have all called this thesis into question and proposed that Christian ways of understanding the work lead to the rise of Science.

Other’s, most notably Numbers and Lindberg, while not wanting to defend the claim that Christianity fostered the rise of Science, also question the conflict thesis. In an anthology they edited entitled God and Nature. Numbers and Lindberg suggest a more nuanced thesis; that the relationship between theology and science has been to complex over the ages for either generalisation to be correct. However both schools, as far as I can tell, reject Whites work as a piece of propaganda. As Collin Russel notes “Draper takes such liberty with history, perpetuating legends as fact that he is rightly avoided today in serious historical study. The same is nearly as true of White, though his prominent apparatus of prolific footnotes may create a misleading impression of meticulous scholarship” ("The Conflict of Science and Religion" in TheEncyclopedia of the History of Science and Religion, New York 2000). John Hedley Brooke the Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at the University of Oxford writes in Science and Religion - Some Historical Perspectives (1991). writes “In its traditional forms, the [conflict] thesis has been largely discredited”.

Similarly Edward Grant Professor Emeritus of the History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University who writes “If revolutionary rational thoughts were expressed in the Age of Reason [the 18th century], they were only made possible because of the long medieval tradition that established the use of reason as one of the most important of human activities” In the same vien Steven Shapin Professor of Sociology at the University of California, San Diego writes "In the late Victorian period it was common to write about the 'warfare between science and religion' and to presume that the two bodies of culture must always have been in conflict. However, it is a very long time since these attitudes have been held by historians of science."

I am sorry PC but your comments about the so called dark ages where the Church suppressed all scientific thinking is false and widely recognized as false. You are perpetuating a discredited 19th century view that few take seriously anymore.

5. Need I mention Galileo? That Galileo saw Aristotle as an adversary was wholly due to the Church's appropriation of The Philsopher, but in evey important respect Galileo's method of observation-based rationality was Aristotle's, whether Galileo knew it or not.

Actually the Galileo example does not fit your picture. As William Shea notes Galileo’s was part of a Platonic revival in Florence. (“Galileo and the Church” in Ronald Numbers and David Lindberg (eds). God and Nature” Historical Essays on the Encounter between Christianity and Science ( Berkley: University of California Press, 1986) 124). He rejected an Aristoleian view of science in favour of a more Platonic view as a result. Stillman Drake ( Galileo (Oxford: Oxford University Press)) Galileo’s strongest opponents were supporters of Aristotle and it was more his calling into question Aristotle that got him into trouble than his disagreements with the Church. Moreover, it was primarily the Aristotleian scientists who sort his prosecution.

Interestingly, the Copernican theory that the earth revolves around the son originates with fourteenth century theologians Burdian and Nicolas d Oresme there theories were based in part on Theological condemnations of Aristotelian Philosophy that had occurred in the previous century. Finally Galileo in developing his views followed the teachings on religion and science propounded by “dark age” writer Augustine of Hippo.

Its amusing to see you cite a Platonist anti Aristotelian thinker, being persecuted by the Aristotelian scientists for following a “dark age” philosopher, as evidence that Aristotelianism lead to liberation from a Platonic dark age way of thinking

6. Newton is not revered for his mystic rambklings or his alchemy; he is revered because his physics integrated and explained such a wealth of actual observations of reality.

Newton’s physics in fact were based on the theological voluntarism of the late middle ages which rejected Aristotelian theories on the ground that God being sovereign freely choose the create the world. This is evident from the preface of Newton’s principia. Again the facts do not fit the simplistic rantings of Ayn Rands followers.

Locke is revered not for wanting to exclude Catholics from the throne and supporting the suppression of atheists, but for explaining that the protection of individual rights is the only legitimate job of governments, and explaining and integrating the method by which individual rights are best protected.

Actually Locke’s argument in the two treatise on civil government is very different from this (unlike so many Libertarians I encounter I have actually read the book several times). Locke in fact grounds rights not in the sovereignty of the individual but in the sovereignty of God, moreover his moral theory is based on the voluntarist accounts of natural law which were developed in opposition to Aristotelian natural law theory and which were based on theological concerns about Aristotle limiting God’s freedom and omnipotence.

Ockham and Scotus and Albertus Magnus are properly revered not because they were Christians, but for their enormous contributions to the popularisation of logic and reason in an age of Christian darkness.

Actually none of these thinkers lived in the so called Dark ages; the first two are from the latter Middle Ages. And Scotus and Ockham in fact were voluntarists. Voluntarism this was a movement based in part on the theological condemnations the Church had made of Aristotle. Once again what we see is not Aristotle bring light to a superstitious church. But a Church offering theologically based objections to Aristotle and the scientific progress being the result of this rejection.

Aquinas is revered not because he was part of the newly founded the Domican Order set up to combat heresy in Europe, but because he opened the door to intellectual freedom in the west, however inadvertently.

Unfortunately again the facts do not support this. During the 'so called' dark ages the official policy towards Jews pagans and heretics was de fact tolerance. Most of the early church supported freedom of religion. It was in the latter middle ages which saw the establishment of Inquisitions to prosecute heresy. Aquinas supported these Inquistions and used reason to defend them. On the other hand Aquinas supported tolerating Jews and non-believers citing the authority of “dark age” theologians as his basis.

***

Its interesting though that when I challenge objectivist orthodoxy with facts LGM responds by name calling and denounces me as like a communist and some who should not be reasoned with.

Who are the dogmatic suppressors of reasoned dialogue again?

Post a Comment