What an odd mix is Eric Clapton. A reserved, almost donnish Englishman, and still one of the world's great guitar heroes. Born and raised far from Mississippi or Chicago, yet he wields unquestionably one of the finest blues guitars the world has heard.

What an odd mix is Eric Clapton. A reserved, almost donnish Englishman, and still one of the world's great guitar heroes. Born and raised far from Mississippi or Chicago, yet he wields unquestionably one of the finest blues guitars the world has heard.And he understands the psychology of creativity too, about which more below.

Clapton however has always been constrained by genre. Listening to much of his music over the years, his blues solos are the moments which are clearly and majestically him, the moments when he really stretches out, and his guitar gently aches and weeps -- at these moments he seems to be playing from and expressing his soul. But over the course of many years the number of solos has been too few, and the song structure within which those solos are contained has too often been too constraining, and to my ear often just too insipid to allow his soul to sing. Most of his albums -- including his latest dreary offering 'Back Down' -- have not unfortunately been crammed full of emotionally and technically challenging blues music, but too often have been mostly featureless terrains of musically- and emotionally-shallow mush-- stretching neither him nor his audience. They have however paid for an awful lot of fine living.

But just occasionally it's possible to hear the real Clapton -- and boy can he play when he wants to! A recent DVD/CD set in which Clapton plays songs from blues legend Robert Johnson (pictured right) is one recent and brilliant example: this captures the real Clapton, playing beautifully, expressively, and from the heart. The blues, it's sometimes said, ain't nothin' but the sound of a good man feelin' bad -- Johnson's songs are the real thing: they ache with emotion; Clapton clearly feels it, and when he does feel it you can hear it in his guitar.

But just occasionally it's possible to hear the real Clapton -- and boy can he play when he wants to! A recent DVD/CD set in which Clapton plays songs from blues legend Robert Johnson (pictured right) is one recent and brilliant example: this captures the real Clapton, playing beautifully, expressively, and from the heart. The blues, it's sometimes said, ain't nothin' but the sound of a good man feelin' bad -- Johnson's songs are the real thing: they ache with emotion; Clapton clearly feels it, and when he does feel it you can hear it in his guitar.He points out however in an interview on the DVD that playing these songs is by no means easy -- Johnson's seemingly simple songs are a mare's nest of difficulties and complexity. Clapton the guitar hero confesses he's not entirely able to play what Johnson played and recorded seventy years ago. Like pianist Art Tatum, listening to Johnson's recordings makes you convinced there's two people playing.

When I first heard him, [says Clapton], I think Keith Richards said this too, that we all thought there was, he was being accompanied by someone, it sounded like it. And it wasn't unusual in those days, I mean, you often had a piano player and a guitar player, or two guitar players. And it wasn't until later that I realized you could do it, what he does. But you have to really, I mean, I've had to, I've had to work really hard in the last few days, to try and do some of the things that I needed to do to play along.Clapton describes his struggle trying to get just one song right, and concludes that getting it exactly right, "I think to do that would be a life's work. I mean, it seriously would be a life's work for any musician." He has problems with one song in particular, Stones in My Passway, and despite never really mastering it, he's clearly relishing the artistic and technical challenge.

And I, and, and, and my, my take on Robert Johnson so far is that it needs two people, to play what he plays and sing at the same time.

Until I and I still can't, I can't do it completely right, I can kind of get an approximation. But, I mean, it's almost one of those things where you listen to it, it just sounds so relaxed. And yet when you come to try it and do it, you find out how almost virtually impossible it is. And I've had to work on this every morning and every night for the last week, to try and just do one song like that. So that's pretty difficult."Pretty difficult" for Eric Clapton means well-nigh impossible for ordinary mortals --- this simple-sounding music is in fact fiendishly difficult to play, which is part of what offers Clapton his reward for playing it. In an interview for the DVD, Clapton describes what he feels when he's playing this difficult music; his description makes fascinating reading for anyone interested in the psychology of creativity, and of what makes people truly happy, satisfied and fulfilled:

Well, it's the closest thing to being truly in the moment I can experience really, I think. If I'm, if I'm just in a social situation, and we're, I mean, me alone, part of me is there, a good deal of it. You know, maybe 75% part of my brain is off somewhere, thinking about what I'm gonna do tomorrow, will, have I got everything I need to make the journey I'm gonna make, etcetera, etcetera. Did I do, did I forget something about what we were supposed to do yesterday.I mean, but doing that kind of work, especially the stuff that we're doing, with just me and the acoustic, requires such concentration that I am, I think this is close as I get to being really in the moment. And then everything, time just sort of stands still, and at the same time seems to go by very quickly. It's all, it's all like, a kind of roller, it's like being in a, in an accident. It's just a blur. But I love it, you know, I love, I love that kind of, when it feels like it's really going well, and, and, and I'm just in tune and in harmony with time. It's a great, it's a great feeling.

Anyone who's ever been fully absorbed in that creative moment will know exactly what he's talking about -- and we don't have to be a world class guitar hero to feel it. Hungarian-US psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes that state as one of "optimal experice, or flow," a state in which you are:

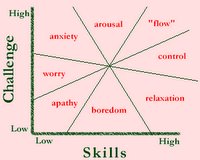

Anyone who's ever been fully absorbed in that creative moment will know exactly what he's talking about -- and we don't have to be a world class guitar hero to feel it. Hungarian-US psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes that state as one of "optimal experice, or flow," a state in which you are:being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you're using your skills to the utmost.Csikszentmihalyi has studied creative and high-achieving individuals, and he describes the phenomenon of their 'being in the flow' in their work as both their defining attribute, and their reward. 'Flow' itself is a function of a person's skills and the challenge before them. "Optimal experience, or flow, occurs when both variables are high," says Csikszentmihalyi. Too simple a challenge for our skills and we feel bored; too much of a challenge and we feel anxiety. But like Red Riding Hood eating Baby Bear's porridge, if things are 'just right' and our skills are being challenged to the right degree, then we too find ourselves in 'flow' in just the way Clapton describes.

Ayn Rand described "productive work [as] the central purpose of a rational man's life, the central value that integrates and determines the hierarchy of all his other values. Reason is the source, the precondition of his productive work – pride is the result." If our work is what integrates us, then being in 'flow' through our work is our psychological reward for doing it well.

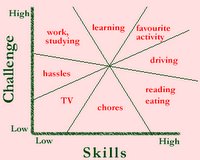

There are a number of implications of Csikszentmihalyi's research, including important implications for career choice, for artistic creativity, for education, and even for how we choose to relax (see image at right). Productive and creative work can be seen not just as important existentially, but also psychologically, and selfishly.

There are a number of implications of Csikszentmihalyi's research, including important implications for career choice, for artistic creativity, for education, and even for how we choose to relax (see image at right). Productive and creative work can be seen not just as important existentially, but also psychologically, and selfishly.Once we understand what 'flow' is and its importance to us, we can seek to maximise our time 'in the flow' rather than simply existing in a drone-lie manner, or engaging in mindless pleasure-seeking. Csikszentmihalyi for example contrasts enjoyment and pleasure, explaining "that the difference was that pleasure lacked a sense of achievement or active contribution to the result." Work or pleasure done 'in flow' need not be tiring; if done properly, it might instead be galvanising!

The North American Montessori Teachers Association have been working with Csikszentmihalyi to apply his model for education with children -- Montessorian David Kahn (who introduced me to the concept of flow in a lecture here in Auckland a few years back) lists eight conditions of "the flow experience," all of which he maintains are found in the Montessori classroom. His introduction to Montessori and Optimal Experience Research (PDF download) is a good place to start understanding the concept of flow, and one example of its concrete application. The 'Brain Channels Thinker of the Year Award - 2000' site also has some great links to find out more.

Linked Articles:

Brain Channels Thinker of the Year Award - 2000: Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, "Flow Theory"

Montessori and Optimal Experience Research (PDF download) - David Kahn

Eric Clapton interview about the CD/DVD "Sessions for Robert J"

Related: Music, Ethics, Objectivism, Science, Education

6 comments:

It's weird reading this. Last night we watched Eric Clapton live from Hyde Park. The blues stuff was, to use your word, 'achingly' good but the stuff like 'wonderful tonight' is dross, and I'd been reflecting on the staggering contrast between the performances. Anyway my young son asked me why Clapton made 'strange faces' and 'played with his eyes closed' during the blues solos. That is a much harder question to answer than it appears.

BTW I think it's Sunday. It better be:-)

You have a very perceptive son, Lindsay, as I'm sure you know. :-)

Seems to me that it's the stuff that is really him is when he really digs deep -- and the blues structure doesn't allow that to be done all the time, more's the pity. But thank god it does allow it - as you say, the stuff like 'wonderful tonight' is dross, and if that was all he played it would be a very sorry night indeed.

I remember seeign him at the Albert Hall when he used to have a 'residency' there over summer, and it was clearly the blues numbers that spun his wheels - he could play the dross in his sleep, and often seemed to be. ;^)

On the question of the eyes: A good solo is not just mechanical, like much of the riffing that a guitarist does. A good jazz or blues solo will 'come from within' and express the musician's soul -- at least, it will if it's done properly. Maybe when 'looking within' it's natural to close your eyes, to help the concentration on the sound, and on yourself, and on really feeling your own response to the music around your solo, and on what you're trying to bring out of yourself to fit that context. Perhaps it can be contrasted with some other things we all do with our eyes in different circumstances: for example, the way we will sometimes look away from someone else if we're talking about something that's particularly close to us; or perhaps when we read something profound, we'll often lift our eys up to the horizon to think about it for a moment, and to somehow help make that thought our own -- somehow looking 'out' helps us link that thought with ourselves, as much perhaps as 'looking in' when playing a sensitive guitar solo helps to 'look in' and make the solo a much more personal one.

"BTW I think it's Sunday. It better be:-)"

Well done. I'd missed that. Ta. :-)

Brian May is the best guitarist.Ever. I guess you have never heard a solo from May.

Clapton sux.

Brian May's a musician?

I first started to think about work and the experience of flow (though I didn't have a name for it then) when I read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance when the main character described the sense of almost merging with the motorcycle he was working on as he became so engrossed in it that time almost stopped

I remember Nathan Astle's comment after his astonishing innings (222 not out?) against England at Lancaster Park a couple of years ago; the fastest ever double-century scored in a test match, full of boundaries and sixes.

'I was just in the zone where everything seemed to go right'.

Post a Comment